For over forty years Roxy Wolfe and Roger Peterson have been close friends. Wolfe, a longtime psychologist, met Peterson in the Doctor of Psychology program at Antioch New England in the early 1980s. She was a student, and he was a co-developer of the program and a professor in it. The two hit it off, and they have remained friends through the intervening decades. Which was part of why Antioch tapped Wolfe to interview Peterson on the occasion of his retirement after a long and storied career at Antioch. In the interview—which is available to watch online—Wolfe’s continued admiration of her former teacher is clear.

This sentiment is part of why in 2010 Wolfe gave a generous gift to help establish the Roger Peterson Speaker Series, an ongoing program that through lectures and conversations explores the possibilities of what clinical psychology can do in the world. This gift is testament to the lasting legacy of this mentor who helped Wolfe believe in her own capacities as a clinician.

Behind the gift, though, there’s a story. The story of Wolfe’s career, which led her to leave her original path in nursing—and to leave her small farm—to help others by working in mental health Wolfe faced many challenges along the way, but this key support from Peterson and her other mentor David Singer helped her build confidence in her passion—and turn it into a thriving and rewarding career.

Finding Her Way to Mental Health

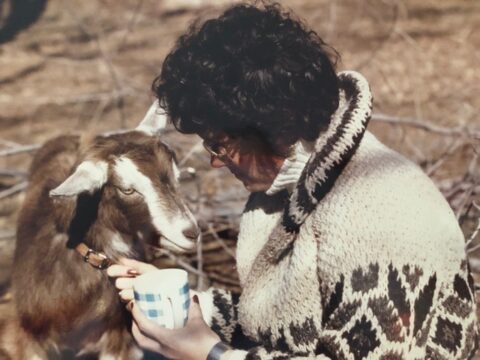

Wolfe didn’t always dream of being a psychologist. “I used to have my maple trees,” she says. “I made maple syrup every year. I grew tomatoes and basil, and I had a food co-op.” This was in her early thirties. She owned a small farm in New Hampshire. Beyond the garden and the maple trees, she kept dairy goats. And she paid the bills by working full-time in ambulatory care. She loved living on her small farm.

It was while balancing the two facets of her life—farming and nursing—that she came to a turning point. She was working with a patient one day when an experience sparked her curiosity for psychology.

It was during her traineeship in the University of New Hampshire MEd Counseling Psychology program. She had been caring for a patient when, as Wolfe describes, “One day, I watched her dissociate.” Although at that time Wolfe had no training in dissociation, she intuitively understood what was happening. The patient didn’t seem present in the room anymore, was no longer responding to outside stimuli or verbal interaction. But Wolfe didn’t feel particularly worried. Instead, she says, “I just sat with her, waited a bit, and she came back.”

This experience of witnessing her patient come in and out of the room mentally, and her own ability to process the episode made her wonder if this was the work she was meant to do. She clearly had an aptitude for it. And she found it interesting and rewarding. So she began searching for doctoral-level psychology programs.

Choosing the Right Program for Her

In 1984, Antioch was the only program within a reasonable distance that had any clinical training. “I thought that made no sense,” she says. “Of course, I wanted clinical training!” Even at schools like Harvard, there was no requirement that psychologists in training actually work with patients. This omission was, in fact, one of the founding aspects of the Antioch PsyD program—the founders believed that practitioners needed clinical training to prepare for clinical practice.

So Wolfe applied to Antioch—and not to any other programs. She was admitted. “It was like a plug and an outlet,” she says. “And the plug looked at the outlet and said, ‘Oh, that’s where I fit!’

She enrolled in the program and immediately loved it. However, she soon found it was harder and harder to continue with both her earlier path and her new pursuit. For months she tried to balance her work, school, and farm life. Eventually, about three months into the doctoral program, the burden of balancing so many different lives came to a head. She found herself having a debilitating migraine headache—and then another. Finally she had to admit that she couldn’t do it all.

“I emptied my barn and moved to a small house in town,” says Wolfe. “It had been a wonderful life, so it was really hard to give that up.” But Wolfe knew she needed a change for her health—and she understood that the PsyD program was where she needed to be. “My life had to change,” she says. ”That speaks to the idea of finding a passion.”

And find a passion she did. Since graduating in 1989, Wolfe has consistently worked as a clinical psychologist with specialties in neuropsychology, trauma, and dissociative disorders. She has helped thousands of people to manage the impact of their past traumas and experiences so that they can successfully move into their future.

During her journey in clinical training she had her own challenges to manage. The compassion and support of her mentors taught her how to provide the level of successful care she continues to do today.

Compassion Leading to Confidence

On Wolfe’s first excursion to Antioch, she met Dr. Roger Peterson and Dr. David Singer, the two psychologists who founded the PsyD program at Antioch New England who would go on to be her mentors. She quickly learned how deeply dedicated both men were to the program and its mission. “A series of good fortune led me to find David Singer and Roger Peterson,” says Wolfe.

Wolfe has many stories from those days, but she especially remembers the time when, as she puts it, David Singer “saved my skin.” With one semester remaining in her pre-doctoral internship, the person in charge of Wolfe’s internship told her internship teacher at Antioch that Wolfe was not doing an adequate job and that she should not receive credit for any of her time there. The news got back to Wolfe. “I was terrified,” she says. “I would lose two years of pre-doctoral internship and would need to start over again.”

When she called the school, Singer answered the phone. She was surprised to be speaking with the director of the program and was afraid that he would be angry. “It tapped every cell in my body that had any insecurity,” she says. Singer wasn’t concerned though, and he responded with clarity. He contacted Wolfe’s supervisor, advocated for her, and ultimately she was able to complete her clinical training. Although it shook her belief in herself, Singer’s moment of kindness stands out as a moment she knew she was on the right path.

But Wolfe formed an even closer mentorship and friendship with Dr. Roger Peterson. She took many classes with him, joined committees he chaired, and he was also her dissertation chair. The two have known each other for close to forty years now. “He is one of the best role models, and mentors, in my entire life,” Wolfe says.

And in turn Peterson recalls Wolfe as “a superb and thoughtful student.” And he says that in the years since she was his student, “She has become a talented and distinguished clinician.”

As a student Wolfe dealt with the usual insecurities of someone starting out on a new path. Peterson sensed this—and helped guide her away from doubt and toward her talents.Wolfe recalls how one day after his class, Peterson gently asked her, “I wonder when will it be that you will stop selling yourself short?” This struck her deeply. She says his acute sensitivity to her insecurities was profound, and it meant so much to her that her mentor, someone she looked up to, saw her abilities and encouraged her to grow them and to be proud of them.

“That’s a gift,” she says. “To be so seen by somebody important in your life. He was giving me permission to have confidence.”

After graduating, Wolfe never lost touch with her friend Peterson. Last year, when Peterson prepared to record a retirement video, he asked for Wolfe to be the student to interview him. She was honored.

“I can’t tell you how touched I am that he asked me to be the interviewer. The man has had hundreds of students,” Wolfe says. “Maybe he asked me because he knows that I love him deeply.”

Peterson says he asked Wolfe to be his interviewer because he deeply values their lifelong friendship. “With Roxy as my interviewer, it was wonderful to feel deeply understood,” he says. “And we share a sense of humor!”

The Roger Peterson Speaker Series

In 2010 Wolfe gave a substantial gift to start the Roger Peterson Speaker Series, and she continues to be a regular donor to keep the series going. It’s a way she can honor the connection, compassion, and work of her mentor. Wolfe says, “This is a tangible gift. This Roger Peterson Speaker Series, it’s so tangible. It’s alive, and it has a future.”

“She’s been the prime mover,” explains Peterson. “It’s not just been me. Roxy did it, and it’s important she gets the credit for its continuation.”

The Roger Peterson Speaker Series allows gifted speakers from across the country to bring differing views to graduate students in the PsyD program. It allows learners to hear from experts outside of the Antioch community, providing new context for important contemporary issues in psychology. For example, last year’s presenter was Dr. Thema Bryant-Davis, Professor of Psychology at Pepperdine University. Her presentation was titled “Healing the Wounds of Racial Trauma: Moving Toward Liberation.”

Wolfe is deeply honored to be a part of the creation of the Roger Peterson Speaker Series. Her gift to the PsyD program will go on to impact many future students. “Roxy has a profound understanding of the vision of our program and its implications throughout all these years,” says Peterson. Her support of the speaker series shows her commitment to helping others, not only as a psychologist, but also as an active member of the Antioch community. It also shows the love and admiration she has for a life-long mentor and friend.