This is the first episode of Season Four of the Seed Field Podcast! To start a great season, we are bringing you a very special conversation with two leaders in higher education: Antioch University’s Chancellor Bill Groves and the President of Otterbein University, John Comerford. A little over a month ago, a plan was announced for the two universities to affiliate with each other, to build a new private, nonprofit university system. In this interview, listeners can learn about both our universities’ histories and their new path forward directly from the two leaders most responsible for making this happen. We also delve into the plans to expand this system beyond these two founding schools, fulfilling this vision that has been boiled down to the phrase: collaboration, not competition. Here’s to the new shared chapter between these two venerable institutions!

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | Simplecast

Episode Notes

To learn more about this affiliation visit antioch.edu/system.

This episode was recorded on August 16, 2022, via Riverside.FM and released August 31, 2022.

The Seed Field Podcast is produced by Antioch University.

The Seed Field Podcast’s host is Jasper Nighthawk, and its editor is Lauren Instenes. Special thanks for this episode goes to Sierra Nicole DeBinion, Karen Hamilton, and Melinda Garland for their contributions.

To access a full transcript and find more information about this and other episodes, visit theseedfield.org. To get updates and be notified about future episodes, follow Antioch University on Facebook.

Guest Bio

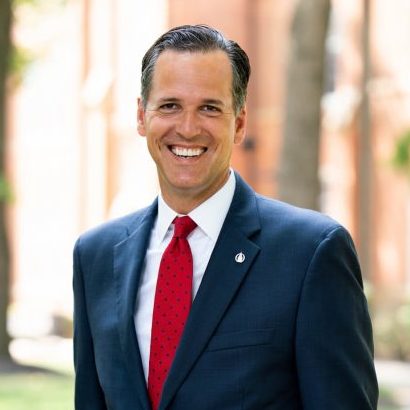

John L. Comerford, Ph.D., began his duties as president of Otterbein University on July 1, 2018. Since then, he has been growing Otterbein University’s commitment to being inclusive, innovative and intentional. He has a strong record of commitment and advocacy for higher education and liberal arts colleges, which he brought to Otterbein when he took his post as the University’s 21st president. Comerford is committed to providing access to affordable higher education while delivering excellence in academic, student life, and career preparation programs.

William R. Groves, JD, is the 22nd President/Chancellor of Antioch University. He has served as Chancellor since 2016 and has focused on three priorities; to reclaim and advance its reputation as an innovator in higher education; to grow programmatically and geographically in ways that will allow Antioch to reach its full potential to advance social, economic, and environmental justice; and to advance and promote the University’s 168 year-long history and heritage around social justice and democracy building.

S4 E1 Transcript

[music]

[00:00:04] Jasper Nighthawk: This is The Seed Field Podcast, the show where Antiochians share their knowledge, tell their stories, and come together to win victories for humanity.

[music]

I’m your host, Jasper Nighthawk. Today, we’re bringing you a very special conversation with two leaders in higher education: Antioch University’s chancellor, Bill Groves, and the president of Otterbein University, John Comerford. A little over a month ago, John and Bill jointly announced a plan for both of our universities to affiliate with each other by pooling their resources together to found a new private nonprofit university system. There’s a lot that goes into this big initiative, and I’ve learned a lot about it from watching their announcement, which was recorded and is live online.

We’ll link to that in our show notes. Here, I’m really excited to have this opportunity to have a more casual conversation and to hear more about this new chapter in both of our university’s histories directly from the two leaders who are most responsible for making this affiliation actually happen. There’s something really exciting about two venerable institutions coming together in a collaborative way to chart a new path and found a new era.

There are plans to expand this system beyond these two founding schools to create a model of working together in service to students and society that will really fulfill this vision that John and Bill and everybody working on this project has boiled down to the phrase: collaboration, not competition. Without further ado, let me introduce our guests. John Comerford is the president of Otterbein University in Ohio. He’s served in this role at Otterbein since 2018. Before that, he was president of Blackburn College in Illinois. He has a long history as a university administrator and holds a PhD in higher education administration. John, welcome to The Seed Field Podcast.

[00:02:02] John Comerford: Jasper, I’m thrilled to be here. Thank you.

[00:02:04] Jasper: Our other guest is the chancellor of Antioch University who oversees our five campuses all around the country, and that’s Bill Groves. Bill has served as Antioch’s chancellor since 2016. Before that, he was university council. He holds a JD and spent over three decades as a lawyer in private practice where one of his major clients was Antioch. This is Bill’s second time appearing on The Seed Field Podcast. Back in Season 1, episode 8, I got to interview him about higher education’s role in democracy. Welcome back to The Seed Field Podcast, Bill.

[00:02:36] Bill Groves: Thank you, Jasper. Glad to be here.

[00:02:38] Jasper: I’m really excited to get into this conversation. We usually start these conversations by disclosing a little bit about ourselves, our story, and where we’re coming to this conversation from. For me, I think it’s useful for listeners who can’t see me, may not know, me to know that I’m a white cis-gendered man. My sexuality is complicated, but as a man married to a woman, I go through the world with a lot of straight privilege. I’m not currently living with a disability and I’m lucky to have stable income and housing these days. Maybe I’ll start with you, John. As much as you’re comfortable, can you share with our listeners where you’re coming to this conversation from?

[00:03:17] John: Oh, I’m happy to Jasper. A little background for folks that are getting to know us, I grew up the child of two college professors. I grew up on college campuses. When my parents couldn’t find a babysitter, they dropped me off at the student union with the roller quarters and told me, “Have a great day,” and I did. There was a dining hall and there was a video arcade. I was just a kid running around a college campus my whole life. My parents both taught math.

They’re retired now. If you take a mathematician plus mathematician, equals an administrator somehow. That’s okay. I was not a good high school student. I just was in a rebellious phase, didn’t do well. College is really what turned me around. It felt like it was mine. I had great supports and mentors. College really made me who I am today. Someone, while I was in college, said, “You could do this for a job. You could stay in college forever.”

I became a student affairs person, and most of my career was in student affairs. I did advancement work for a little while before I went to Blackburn College, but I just love that what we do is transformational work. I also am married to my wife Rachel, have three kids, live here in Westerville, Ohio, and have enjoyed a great deal of privilege and blessings in our lives. Very grateful for that.

[00:04:30] Jasper: That’s great. Thank you, John. Let’s hand it over to you, Bill. As much as you’re comfortable, can you tell us where you’re coming to this conversation from?

[00:04:37] Bill: Absolutely. Thank you. I’d like to share a little bit more than probably I have ever shared before, even on your first podcast. Following up on John, I grew up in a family of engineers. My dad was an engineer and vice president of research and technology for a fortune 500 company. He raised a bunch of mathematicians, too, John, but I was not one of them. They all went into engineering except Bill who went to law school, so I was the loner in the family. I have an identical twin brother.

I went to school thinking I was going to be a doctor. I had been the high school national debate champion. Everybody thought I should be a lawyer instead, and that’s somehow it worked out. Did debate in college, and ended up getting married. Having two children came out at age 42, have a partner for 22 years now named Joel. We have three grandchildren, one of whom was born a week ago. Her name is Serenity and I hope she lives up to her name.

Obviously, I identify as LGBTQ+. I am white cis. My educational background, as I just mentioned, is in law. I did do 30-some years of practice in private practice, started working with Antioch in 1979 as a client, continued to do much of their work as part of their legal team up until I came in house in 2010 and five years later, became chancellor. That’s my trajectory. There are many stories I can tell about my history with Antioch and maybe we’ll weave that in later in the conversation. Thank you.

[00:06:25] Jasper: Yes. Thank you, Bill, for sharing so much about yourself and an interesting story. I had no idea that you were a national debate champion.

[00:06:33] Bill: It’s one of those little-known secrets. People think I may be argumentative.

[00:06:38] Jasper: Actually, I want to jump into Bill. You were starting to talk about some of the history of your institution, but I want to start with John and Otterbein. I don’t actually know that much about Otterbein. I’ve tried to get up to speed around the affiliation. For me, and for some, our other listeners who don’t know very much about your institution, I was hoping you could give us the elevator pitch for Otterbein, why it’s important, where it’s come from, and why you like working there.

[00:07:04] John: I’d love to. It’s going to be a little long of an elevator ride, maybe the Sears Tower kind of level, just because there’s so much to share. We were founded 175 years ago, 1847, affiliated with a church that was founded in Baltimore. Our namesake Otterbein is from the founder of that church in Baltimore who founded the church to be the first abolitionist church, thought that a church needed to stand up, that slavery was wrong. Several local leaders, pastors, founded the college named after Otterbein here in Westerville in 1847.

Again, all abolitionists, an important stop on the underground railroad. Our founders’ houses right by campus were stops. That was always in the center of things. Ever since then, we’ve had this thing we say that Otterbein tries to do the right thing before it’s popular. We don’t always get it right, of course, but if you go back to the founding, we were the first college founded co-ed. The first college to have women on the faculty, the first college to have women and men in the same classrooms, while there were some colleges that admitted women they had a separate educational track than the men who were in.

Typically, we never did that. Our founders recruited our first student of color before the Civil War. To be honest, I think he only made it six or eight weeks before he was harassed out of town. We were not quite ready for that, but at least they tried early on. That forwarded into World War II. Otterbein educated Japanese Americans that were recruited out of internment camps during the war. In the ’60s, during the student protest era, we actually integrated students into our shared governance system.

Students had equal voice to faculty in the university Senate. There are two students on the board of trustees along with two faculty members, and so it’s a very integrative thing. We invented the integrative study curriculum. Now, most colleges do this with undergraduates where you have to take courses that make you take all these disparate fields and put them together and apply them to a problem we invented in the ’60s.

Everyone else does that now, which is fantastic. Through to today, now it’s about access and affordability and diversity inclusion. We’re very lucky to have a very diverse student body. We think that leveraging this new partnership and this new national system into serving populations that deserve to be served but always haven’t been well served by American higher education is really going to be at the heart of what we do.

[00:09:25] Jasper: Thank you for that. I feel like you condensed a great deal down into our elevator ride. That’s a very proud history. Knowing more of Antioch’s history feels well matched as a partner institution. Bill, for our listeners from Otterbein or from elsewhere who don’t know that much about Antioch University, could you give us a quick explanation of what makes Antioch special and kind of how our history leads to this moment?

[00:09:49] Bill: Oh, thanks, Jasper. It’s interesting. A lot of the things that we claim as being among the first Otterbein is the first. We were among the first and then with many of those metrics that John just mentioned. We were established in 1852. About four years after Otterbein, we immediately began enrolling African Americans and women. We had a woman faculty member. She happened to be related to Horace Mann, but she was a woman and she was paid on the same salary scale as the men.

These were all somewhat first and we were obviously being led at that point by Horace Mann who was our first president. I think that he has been the soul of this institution from the beginning. As someone who was the father of public education in the United States, he brought with him a connection between the country’s journey as a democracy and education. He fervently believed that in order for democracy to survive, that a population needed to be educated and it needed to be more than just a grammar school education.

This was his next journey, what I call his next democracy project was Antioch College at the time. The other notable figure in Antioch’s history is Arthur Morgan who was president in the 1920s. What he did when he was here was he reconceived of the undergraduate education as being preparatory for careers and not just enough to make people interesting at cocktail parties and dinners. In order to do that, he believed that students should be out learning what the real world is about, and so he created the first co-op program for undergraduate school.

There had been some co-op programs in engineering and other graduate programs before, but this was the first co-op that was actually part of the curriculum required for all undergraduate students. That continues actually to be the model for undergraduate education at Antioch College, that is, you were on campus for two quarters and you were off campus working at a co-op opportunity for one quarter every year. The experiential learning part of higher education is something that Arthur Morgan really helped instill in Antioch College and then Antioch University at large.

Of course, in 1964, we went beyond the four walls of Antioch College and began our first graduate education programs in what was then Putney Vermont. It is now the key New Hampshire Campus. It was the first graduate school of the university. At some point, we had as many as 35 or more graduate facilities across the country from Washington, DC, in Baltimore area and Philadelphia across to San Francisco and Seattle and San Antonio and Hawaii and Alaska. It was everywhere.

It was basically let 1000 Antioch bloom under the leadership of President James Dixon in the 1960s and 1970s and eventually that contracted down to the campuses that we have today. Of course, we closed the college campus in 2008. We entered into discussions with an alumni group to reform the college and they created a new college corporation to do that just to allay any confusion that people might have out there. We are two separate institutions now with the name Antioch. They licensed the name Antioch from Antioch University, but they are the only ones who can use the words Antioch College.

[00:13:34] Jasper: Thank you for clarifying that and that great history, our proud history. John, did you have something you wanted to add?

[00:13:42] John: I think we need some history students or someone to go research because I’m sure our founders would’ve had to be connected or know each other because these two schools founded four or five years apart on abolitionist principals being co-ed from– these sort of things, these were rare ideas at the time, and to see these two histories side by side is really remarkable.

[00:14:02] Jasper: That comparison is natural here and it is remarkable just how closely they parallel each other, but as independent institutions for the first 170 years or so. John, can you tell us a little bit about this vision for a new system where you guys have signed an agreement to try and make it happen?

[00:14:20] John: Yes. Again, I’ll try to be brief about it, but the fundamental idea is that we will be able to serve more students in more programs and more locations with more diversity than we could alone. The fundamental ideas that there are lots of colleges out there like Otterbein, that are primarily traditional undergraduate institutions. We have 2,200, 2,300 traditional, 18 to 22-year-old undergraduates on a residential campus. We have a small graduate program about 300 or so, graduate students.

The traditional thing is in the heart of Otterbein. Most of our alums come from that program, and when you think of Otterbein, that’s what you think of. We know that that market is important, but challenged. I’ll just be honest, listeners, no one had enough kids. There’s not enough 18-year-olds to go around, it’s an issue. It’s not a growth part of the market. We’ve done a lot to serve underserved populations that’s led to the growth and diversity on campus and a lot of need-based aid and things like that, but still, it’s just going to be a challenging market in that traditional paradigm.

The growth is going to be all about adult learners. If you think about workforce needs, if you think about underserved populations, there are tens of millions of adults in the United States of America who at some point set out to get a college degree and get their credential and just never got it, or maybe need to go reskill now and get that master’s degree and things like that. There’s a huge potential there.

That’s not where we specialize, but it is where Antioch specializes, with these multiple campuses and programs that really serve that market. Can we have our cake and eat it too here in inviting schools like Otterbein to keep their distinctive traditional programs, but through Antioch, be able to deliver adult education at scale nationally, hopefully serving tens of thousands of students and transforming lives and workforces everywhere we go?

[00:16:06] Jasper: That’s such a great vision, and I think has that spirit of innovation to try to carry the work of your institution forward, but not be constrained by it.

[00:16:18] John: Jasper, the timing is no accident here. The pandemic and now the economic uncertainty we face in inflation, this has been a wake-up call. A lot of institutions public, private, everything have been really affected by this as the students and families that they serve have been affected by this. The need for innovation and the need to think of higher ed as not a zero-sum game.

The way we think about it is if I get a student in Otterbein, we took one away from Ohio State or Ohio residence, it’s a zero-sum game. There’s so much need out there for education in these adult learners that you don’t have to think zero-sum. This is not a competition. If we work together, we can serve more deserving students and change those lives. It’s a mentality shift that I think is long overdue.

[00:17:06] Jasper: Can you tell us a little bit about how this collaboration, this new system might actually impact the experience of Otterbein students?

[00:17:18] John: Our traditional students we imagine being part of this system we’re building will have some meaningful benefits without changing the heart of the experience. They’ll still be Otterbein students on our campus in Westerville doing the residential liberal arts college thing and we’re never going to give up on that. Through the scale of the system, we imagine there’ll be lots of pathways for accelerated degrees.

You’re admitted as a new student at Otterbein into a 3+2, into a master’s degree at Antioch. You have an accelerated pathway to get the credentials and degrees that you want to get. We imagine doing some services together. Imagine this network of schools, we could do study abroad together and internships and corporate connections together so we can be operating more at scale and giving those students more opportunities. We’ve also found, Jasper, every time we get our people together, our faculty and Antioch faculty, or whoever, suddenly like 16 new ideas come up.

We can’t even imagine the number of possibilities, but for Otterbein in particular, we will begin to market the system idea to our traditional population. While the real work is happening with the adult learners through Antioch, we will market even to the 18-year-olds, we’re going to say Otterbein University, where you get the intimacy of the small campus experience with the resources and power of a large university behind it, because you’re going to have some of these abilities that you’ll get through the scale of the system without sacrificing the small classrooms and definitely know your name and all the stuff that really makes Otterbein such a special community.

[00:18:45] Jasper: It’s inspiring hearing you talk about that. Bill, I wonder if you could add to that and give us the vision from the Antioch side of this system.

[00:18:53] Bill: Thanks, Jasper, and thanks, John. The vision you laid out is exactly what we had hoped to achieve. We started a process about three years ago of looking at affiliation as a means of ensuring the long-term sustainability of Antioch and growing Antioch, achieving more in terms of our mission and reach of that mission, then we could do it alone. I think that the bottom line here is anyone in higher education knows that there will be a consolidation of the 5,000-plus institutions over the next years because of just the pressures within the business model, and scale matters. Scale matters. The larger we are, the more we are able to achieve our mission and have sustainability over the long run. We did want to just grow as a business proposition. We wanted to grow as a mission proposition, and it has to be both, or we don’t think it works. As we set forth in our efforts to find a really amazing partner to start this process with, mission was on top of the list. Mission of educating, not just for careers and preparation for career paths, but also for the things that were important to Otterbein at its beginning and Antioch with its beginning with Horace Mann and that is educating for social justice and democracy.

We wanted institutions to partner with who were part of that mission, who embraced that mission, have a history and heritage of that mission. Our vision was to create a social justice league of universities that we could use to distinguish ourselves from other universities and other systems out there. I believe, and I think John does too, that young people today want to make an impact on the world. They don’t just want a career, they want to make an impact on the world. They want to be good global citizens and they don’t want to wait to do that until after graduation. They actually want to start that now.

They want to know that the institution that they are associated with is someone who holds the values that they do and that can make an impact in the world like they want to make an impact in the world. My vision and our vision has been that this is a national organization, a national system comprised of multiple higher educational institutions with the complimentary program set that will allow us to leverage what they do and what we do in ways that provide benefit to the students and allow us to extend our mission beyond our current footprints and our current programmatic mix.

[00:21:48] Jasper: I know you’ve taken it seriously trying to find the right people to partner with and you’ll continue to do that, but maybe one of you could sketch out a little bit of the vision of what other partner institutions might look like. I know you’re in the middle of founding this new system, but what are you looking for in further partners?

[00:22:08] John: Bill said it. It’s got to start with that mission. This is about social justice and lifting up underserved people. We are the gatekeepers as educators to the American dream. The difference between the life with the degree and life without a degree is, not in every case, but is often the difference between a paycheck to paycheck, life in poverty or on the edge of poverty, and a secure middle-class existence in our country. We have to be democratic about the way we allocate that.

I say that with all due respect to other institutions, many of them use those words. When you look at what they’re actually doing, they’re trying to recruit 30 ICT students with 4.0 GPAs and trying to climb in the rankings and whatever stupid magazine and that is in fact contrary to social justice in its heart. You’re overserving the already overserved and so that doesn’t make any sense. If your mission is to get to the top 10 list and whatever, then serving underserved populations is not going to help you get there.

This is not the system for you. That mission alignment is really, really important. Then we’ve already heard from a dozen or so institutions just introductory conversations. We’re not sure where that’ll head and I think the phone will keep ringing as we hear from more that are interested in this approach and this mission and this business model. I would imagine we’d be looking for programmatic diversity. They’re bringing programs that neither Otterbein or Antioch or other potential partners have. We can add those to the mix of things, we can scale to a national scope.

We’d be looking for different geography so that if there’s locations in Dallas or New York or Boston or whatever, there are populations to be served as opposed to overlapping where we already are. We need to set up a process over the next 10, 11 months to really start to vet some of these conversations because we’ve said this is complicated enough with two schools. We’ll proceed through the regulatory, the Higher Learning Commission on the approvals with the two parties while we’re having these parallel conversations with these other schools, that could then quickly hopefully join up in the system as soon as we get our approvals.

[00:24:10] Jasper: That makes total sense from a process standpoint. Bill, do you have anything you can add to this?

[00:24:16] Bill: I’ll just emphasize a couple of things that John’s already said. The primary criteria in looking at any future partners is mission and then the final thing I’ll throw in there would be financial stability. We really wanted to do this affiliation with Otterbein and start down this path of affiliation at a strategic time, not at a time when one or the other of us is about ready to go under and too many institutions have waited until the 11th and a half hour to make changes like this.

John and I both believe that these are the kinds of transformative changes that are going to happen in higher education and we need to be part of it and we need to be part of it early. Those are the criteria that I would lay out there. Again, the vision is that these would all be institutions that would add to that synergy, add to that ability to leverage, add to the choices the students will have, and create an amazing national system out of this that not one of us could do on our own.

[00:25:21] Jasper: I think that idea of a stitch in time saves nine is not a bad one to move from a position of strength. I’ve heard this described as what you announced last month is an engagement. Then you guys are planning for the big wedding in 12 months or 11 months from now. What you were saying Bill was reminding me of the fact that if you’re getting married to somebody, you want to be coming from a position of strength, not desperation, and the same from them. It sounds like both of your institutions are in that place. I think that I want to push on that analogy a little bit more just to know the actual mechanics of how this is coming together. Is this going to be a merger or is one institution going to have more power than the other institution?

[00:26:06] Bill: It’s not a merger. I think that’s the thing that we would like to drive home the most in this podcast. These are not mergers and this is the distinction between this affiliation system that we are trying to create and some of the transactions that you may be witnessing in other higher educational transactions out there that have taken place over the last few years. Why we don’t want it to be a merger? Because we want to make sure that each organization, each institution retains its identity, there’s value to that.

We don’t want to lose that value. There’s brand value to that, there’s historic heritage to be taken into consideration. Frankly, there’s just the fact that the people associated with those institutions, including Antioch and Otterbein have worked for generations to build a system and a university that they are very proud of and we don’t want to lose that through a merger. In this affiliation process, the parties retain their corporate identity. They retain a board, they retain their name, they retain their accreditation.

There will be a parent organization and a parent board that will be the umbrella organization over the affiliates and there is some control that they would continue to have over the affiliates. For the large part, each individual institution continues to run its own shop. There is an amazing amount of work that’s already going on between Otterbein and John and our group. I think he’s already mentioned just how much positive energy seems to come out of those meetings.

It’s only been a month now since we made the announcement. Now all faculty know the identity of the other party that we have been talking about in the very general way for the last year. I would just describe that for the most part, I’ve seen nothing but enthusiasm. The more people talk to each other that enthusiasm grows as John just said. There’s just a real connection every time our two groups get together as recently as last week to start talking about some of the programmatic opportunities that we have as a system.

[00:28:24] Jasper: That makes so much sense. You guys have been mentioning these pathways and these opportunities for undergraduate, 3+2 programs. Now, I was wondering if there are any of them– I know nothing is written in stone yet, but if there were any that you could tease for us of potential actual specific programs that could come out of this partnership.

[00:28:47] John: The cool part about starting with these two schools is we fit together like puzzle pieces. What Antioch does serve adult learners at scale in multiple locations we don’t do at scale and even programmatically. Antioch’s psychology program, environmental science, the MFA program, these are things that we don’t have. Likewise, most of what Otterbein has at the graduate level Antioch doesn’t have. We have a huge nursing program and health sciences like athletic training and things like that, that we can really imagine leveraging quickly.

We’re already imagining opportunities to bring Antioch programs to Central Ohio and to bring Otterbein programs under the Antioch flag. We’re not going to recreate Otterbein brand, but under Antioch flag to Antioch locations and that’s just what we have right now. Then we start to build new programs and new locations and there’s no limit then. There are so many opportunities just with what we have today that it’s hard to keep track of all these opportunities.

[00:29:49] Bill: It’s really hard, Jasper, to map out on this podcast all the opportunities because they’re still evolving. Most of those conversations have been between the academic leadership of the two institutions, so I’m the least qualified person to be answering that specific question. I would just like to tease people’s imaginations a little bit and say, imagine if we had a program for nurse practitioners that had a concentration in psychology for psychiatric nurse practitioning.

That would be a great way of using the expertise of both of our faculties to develop a concentration. Imagine if we had an environmental studies program in California that involve faculty from both institutions because they have faculty that teach this at the undergraduate level or hire new faculty with expertise in areas that we’re seeking out there. The pathways for undergraduate students, imagine we have 30% of our undergraduate students end up in one of our graduate programs. Having more undergraduate students looking at our graduate programs from Otterbein is already to me a no-brainer.

It gives them opportunities. It gives us an opportunity to think about expanding our programs into Ohio or more distance learning opportunities for students. Then I would just like to pique everybody’s imagination, too, about what’s possible beyond these two founding members. Imagine the next institutions bring to us a program, maybe in a law school, a law school that has graduate programs in legal studies, perhaps environmental legal studies, which really interacts with our environmental studies program. Then, of course, health sciences.

They have nursing, we have psychology and counseling. What we don’t have is the whole allied health area. They also have some degrees in allied health, but physical therapy, occupational therapy. These are all programs that could become part of this portfolio and which could all be made to live up to our social justice mission, like our psychology and environmental studies programs and education programs. There is a way to make those all consistent with our mission. I think everyone knows that, but I just want to lay that out there. We’re not doing any of these academic initiatives without thinking about how they connect to our mission.

[00:32:25] John: I love the lawyer always brings up the law school as an example. It’s well done.

[00:32:30] Jasper: I noticed that too. No, I love that. I love both of you sharing your enthusiasm and your imagination of what is possible leading from that place of what can we pull off. I think sometimes you can lead from a negative place and as Bill, you, and I were talking about this the other day that you really need the enthusiasm to accomplish anything in this world. I think hearing this, who couldn’t help but be enthusiastic?

[00:32:56] Bill: I think I said, nothing great happens without enthusiasm. I think that part of what I am so glad to see is the enthusiasm among our faculty and staff, especially when they’re in the same room together. It is just infectious and it just gives me and John, both, I’m sure, a huge amount of confidence that this will be successful and we will get to the vision that we have in our head.

[00:33:23] Jasper: Yes.

[00:33:24] John: If you think about who works at our institutions, no one works in education to get rich, just in case you didn’t know that. These are mission-oriented people. The idea of this is not some rankings, prestige, or leadism thing. It’s a chance to broaden our mission and serve more deserving students and do exciting things. That spirit, I think, is catching at a time that’s otherwise largely challenging for higher ed.

That we’re going to not hunker down in our trench and wait for it all to pass, which I think is some institutional strategies at the moment, like normal’s going to come back tomorrow. I don’t think normal’s coming back. This is a chance to be proactive instead of reactive in this environment. I think our timing is fantastic and higher ed desperately needs leadership for a new model. This is going to be one of those new models.

[00:34:09] Jasper: John, I want to draw you out on something you were very enthusiastic about in the announcement, which is the way that this can explain into and expand Otterbein’s emphasis on jobs training and preparing students and matching people and careers in the Columbus area and across the nation. You specifically brought up how Intel is planning this $20 billion facility in Columbus, and you’re advocating to be the educational partner with that institution. Maybe you could just give us a little bit of your excitement about how this new system can affect specific things like that, but also just the broader connections with the world of business and job training.

[00:34:54] John: Yes, Jasper. By the way, Intel’s now up to $100 billion investment. Well, what’s 80 billion between friends? It’s a rounding error. No worries.

[00:35:02] Bill: You have 20 billion here and 20 billion there starts to add out to real money, right?

[00:35:08] John: Yes. We just need a couple billion of that and we’ll be good. I wouldn’t complain that much. No, I think one of the things that needs rethought about American higher education is we traditionally put on academic programs and we cross our fingers and we hope it’s what employers want, but we don’t really engage the employers in the process. At Otterbein, we opened a building five years ago now called The Point where we actually have employers on campus in a building we’ve had fortune 500 companies through .com, startups, and nonprofits in that space.

A condition of them being in the building is that they work with Otterbein faculty and undergraduates in their work. It’s bringing the outside into the academy and being more intentional about that connection. I hope that instead of just putting up academic programs, because we hope that students come and we hope it’s what employers want, that we engage in going out to employers for profit, nonprofit, all types, and say, “What do you need?”

Then building programs that feed those needs, because then we can say to students, “Hey, listen, we know this program is going to lead you to these types of positions. We know that we can use the cross-cultural possibilities between the company and the institution to improve both.” Wouldn’t that be a better model of an educational system than just this typical arms-length relationship we’ve had in the past? At least that’s the goal.

[00:36:34] Jasper: That’s lovely. We are nearing the end of the time that we have here. I don’t want to keep either of you long as I know you have great responsibilities to both of your institutions. I thought a good place to close is to come back to this theme of democracy and higher education’s role in promoting democracy. Bill, I know you’ve spoken about this to the Antioch community at a great deal of length in different forums and venues. Maybe we could start with you, John, how you see democracy and the promotion of social justice coming into this system. Then I also want to hear your feelings on this, Bill, and maybe we can leave it there.

[00:37:16] John: Yes, Jasper, I think there’s just so many ways that we have a critical role to play in furthering and enhancing the American democratic experiment. That starts in my mind with access and affordability questions. We know that a college education leads to more critical thinking, more civic engagement, and just better citizenry. In general, that we have an educated citizenry is really important. If higher education, if college is only for those who already have the means, then democracy will fail. That doesn’t make any sense.

If this is the doorway into a functioning democracy, we have to be democratic in how it’s applied and how it’s accessible to Americans, not just your 18-year-olds, but adult learners and everyone else. It’s not just an economic thing, it’s a democratic thing. The other thing that’s high on my mind is there are increasingly few spaces where you can disagree without being disagreeable. We have segregated ourselves and you can see in the data how we’re now living near people that share our viewpoints and share our backgrounds.

We’re just living in this world where we rarely interact and have a relationship with someone who thinks differently. We have different news stations that we watch. We’re just in different worlds with different facts even at this point. College campuses can be a place where people can disagree in an intellectual environment, learn from one another, become better because of that interaction, as opposed to dividing everyone into two camps: allies and enemies. The world is not that simple. We need to be models on our campuses in our programs about that inclusivity because our society desperately needs it.

[00:38:57] Jasper: Yes. You have a great ability to distill things down into the pitch.

[00:39:01] John: I just need long elevator rides, Jasper. That’s all.

[00:39:06] Jasper: I love that. Bill, can you expand a little bit on this and talk about how that ties into this larger system that you both are starting?

[00:39:14] Bill: I could talk about this for hours, so I’m going to give you as much as I can in about 30 seconds. I like John think that higher education owes democracy a little bit more than preparing people for careers. That’s all important, but it’s not the only thing that higher education has responsibility for. Horace Mann knew that and so did the founders of Otterbein know that. I got asked a question by one of the journalists who was interviewing me for an article in a publication following our announcement. He said, “Well, if I’m an engineering student,” and I believe he was an engineering student, “why the hell do I want to know about government?” Well, that was a really good question, but I think that people need to know a little bit more than how to prepare for the career from college, because they’re not getting even a basic civics education anymore anywhere else. Most people learned about the constitution in church and it’s wrong.

I think that we have a responsibility to embed within our curriculum a certain amount of knowledge about what it takes to be good citizens, how to be critical thinkers, how to question facts, but believe in facts and to not believe in this alternative reality that you want to create and get into and get comfortable with for a justification for a position that is just not based in reality. This is all part of education. It’s part of the curriculum that we teach. Being alert to injustice is something we all ought to be taught how to do and being alert to how we improve our democracy and move forward in our careers with understanding that we are also citizens of this country, this nation and this world, and we ought to participate in that.

[00:41:03] Jasper: Yes. Well, thank you both gentlemen for sitting down here today for this conversation. It’s been enlightening for me and I’m excited. I wish you tons of luck in your parts in this work. I’m excited for what it means for me too as an employee of one of these schools.

[00:41:20] Bill: Thank you, Jasper.

[00:41:21] John: Jasper, we should make this a regular thing. Every six months or year, we do an update podcast for all the new exciting partnerships and new programs, and new stuff we’re doing.

[00:41:28] Jasper: That’s a great idea.

[00:41:29] John: Keep tuning in.

[00:41:30] Jasper: All right. Yes. Our listeners, we’ll be back in a year to see how the wedding went.

[00:41:34] Bill: All right.

[00:41:42] Jasper: If you want to learn more about the affiliation between Antioch University and Otterbein University that we’ve been talking about, visit antioch.edu/system. There’s an FAQ, recordings of the announcement, and much more. We’ll put the link to that page in our show notes. We post these show notes on our website, theseedfield.org, where you’ll also find full episode transcripts, prior episodes, and more.

The Seed Field Podcast is produced by Antioch University. Our editor is Lauren Instenes. A special thanks to Sierra Nicole DeBinion, Karen Hamilton, and Melinda Garland. Thank you for spending your time with us today. That’s it for this episode. We hope to see you next time. Don’t forget to plant a seed, sow a cause, and win a victory for humanity. From Antioch University, this has been The Seed Field Podcast.

[00:42:55] [END OF AUDIO]