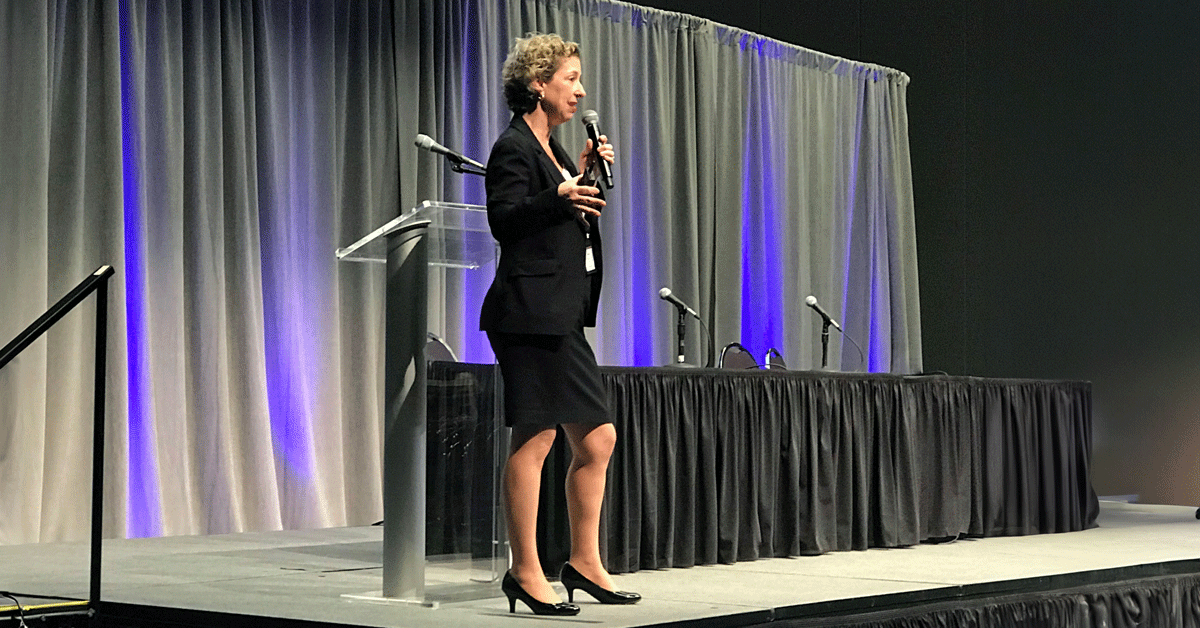

As a child in public school, Maura Hart never once felt safe in the classroom. She didn’t know exactly why. She just knew she wasn’t going to open her mouth. Today, Hart has a better understanding of classroom dynamics, one born of over 25 years working in the American education system. She’s been a classroom teacher and an educational consultant to school districts and state departments of education; currently, she is Assistant Director of Capacity Development at the University of Kansas’ SWIFT Education Center and Adjunct Faculty in Antioch University’s School of Education. So she has had plenty of time to figure out what kept her quiet those many years ago. It’s actually quite simple. As she puts it, “We can’t learn if we’re not safe.”

Hart has devoted her career to supporting educators to make classrooms places where students feel safe and capable of learning. To that end, she is teaching the class “Rightful Presence in the Experiential Classroom.” This course is offered in the Critical Skills concentration in Antioch’s MEd for Experienced Educators. It builds on the concept of rightful presence, a methodology that seeks to combat systemic racism by validating each student’s inherent value and their right to be in the classroom, regardless of race or ability.

This goes beyond the idea of welcoming all students because welcoming implies a guest/host power dynamic. Rightful presence validates a student’s true belonging. They have a right to be present in the classroom. Not only does rightful presence celebrate their culture and values, but it’s also an assurance that the class will be learning about the very things that make each student unique.

This is a core idea within the Critical Skills Classroom framework and one that Hart believes has radical potential. As Hart says, “If you’re a classroom teacher, and it’s a real struggle, and you’re thinking about leaving, but that’s breaking your heart, try it out.” She continues, “You’ll find meaning and power in teaching using the critical skills classroom methodology.”

Making Teachers’ Jobs Easier

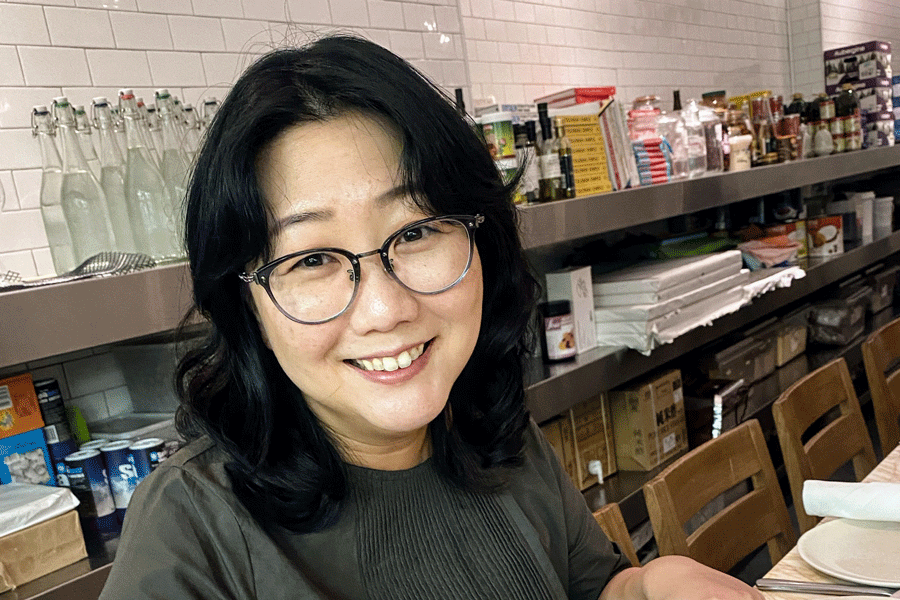

Laura Thomas, Core Faculty and Director of the Experienced Educators Program says that this course is a key part of the Critical Skills Classroom. She explains, “We decided to offer this course specifically because students are often excluded from inquiry-driven learning opportunities like problem-based learning because of prevailing beliefs that these ways of learning must be ‘earned’ through the demonstration of competencies via traditional assessment systems.”

Problem-based learning is a technique in which students work in groups to solve open-ended problems. Thomas feels that this kind of learning should be available to all students, regardless of race, class, or ability. It’s a student-centered approach that encourages kids to take ownership of their own learning and helps them develop skills that benefit them well into adulthood.

In a Critical Skills classroom, the teacher asks the students what they want to learn, selecting texts that reflect the culture and values of the students. Students develop skills such as critical thinking, decision-making, and communication. The critical skills classroom integrates problem-based, experiential, and collaborative learning.

For teachers, this can actually make their jobs easier. The Critical Skills classroom gives students some of the decision-making power and responsibility, allowing them to help make most of the decisions about what and how they will learn. This takes the pressure off teachers and helps to support the Rightful Presence of every student.

How Social-Emotional Skills Support Experiential Learning

Imagine a traditional classroom where the students are lined up in rows, the teacher stands at the front and lectures, and the students do what is assigned. The Critical Skills classroom is the opposite of that, a complete paradigm shift where the students are in control of what they learn and how they learn it.

“[The students] have autonomy, and they have the ability to make decisions and direct the learning in the way that makes the most sense for them,” Hart says. “They have the capability to fail and to learn from that. They have capability to build on each other’s ideas and shift and direct where they go with their learning.”

This level of student-guided learning can directly impact the curriculum. For instance, students pick out their own texts that they will read based on their own cultures, values, and interests. The teacher explains to the students what the larger learning objectives are that they’re required to cover. At the upper grade levels the teachers facilitate the students to identify various options and ways that the class could meet those objectives. It’s in an ongoing conversation between the students and the teacher that the plans for the class are determined.

In this way, the teacher can meet their objectives, and the students will learn what they are required to learn, but the way in which this happens is revolutionized.

Because the Critical Skills classroom relies so heavily on collaboration, social-emotional learning serves as the foundation. “We won’t get far in either camp unless we teach children the skills, attitudes, and dispositions they need in order to collaborate, accept, and understand one another and to embrace diversity,” Hart says.

This ties in with the concept of rightful presence because, as Hart explains, the Critical Skills classroom “empowers the student to be able to be rightfully present and understand and accept the rightful presence of others.” Because students are continually collaborating not just on projects but on determining the shape of the class, they continually interface and support each other.

Students in classrooms like this are continually put in situations where they learn how to work together so that they can make the best decisions possible regarding what they want to focus on and what texts they want to read. Social-emotional learning doesn’t just happen in the first six weeks of class, Hart explains, but rather it’s a part of everything they do in the critical skills classroom.

Making Classrooms Safe—And Making Teaching Easy

When Hart employed these techniques during her work as a classroom teacher, she found it to be so effective that, in fact, she eventually quit public school teaching and began sharing these tools through educating other teachers. “In part, I left because I was bored,” she explains. “Because my students were totally engaged.”

For Hart, her own experiences have taught her that, as she puts it, “it is possible for teachers to have their job be easier.” It’s not an overnight change, she says, but “like anything else, it will be work. It will be a year or three of work for them to shift.”

Hart still loves to share some of the tools and experiences she had during her career as a classroom teacher. One of these tools is setting up explicit contracts with her students. Within that contract she always included certain non-negotiables, especially around safety—and affirming each student’s right to be present in the classroom.

One of her non-negotiables would usually be “no put-downs.” Since put-downs are a common way that young people communicate and interact, she would simply require a child who has given a put-down to immediately say two nice things about the other student. In this way, she ensured everyone felt safe and comfortable in her classroom.

Hart has come a long way from being the child who didn’t feel safe in the classroom. First, she became a teacher who made children feel safe. Now, she’s helping other teachers learn best practices for ensuring that every student feels true belonging.