When Caryn Park was a small child, her parents moved the family from South Korea, where she was born, to the U.S. so that they could pursue their education. While her parents were international students, Park found herself enrolled in a public school classroom in a small midwestern town. She had to learn the language, and she also had to learn, she explains today, “this whole different way of being, of relating to other people.” She learned English so well that she forgot how to speak Korean. In many ways, she was living up to our society’s expectation that immigrants must abandon customs, traditions, and language to become American. But that wasn’t her parents’ plan, and after six years they moved the family back to South Korea. She re-learned the language of her birth.

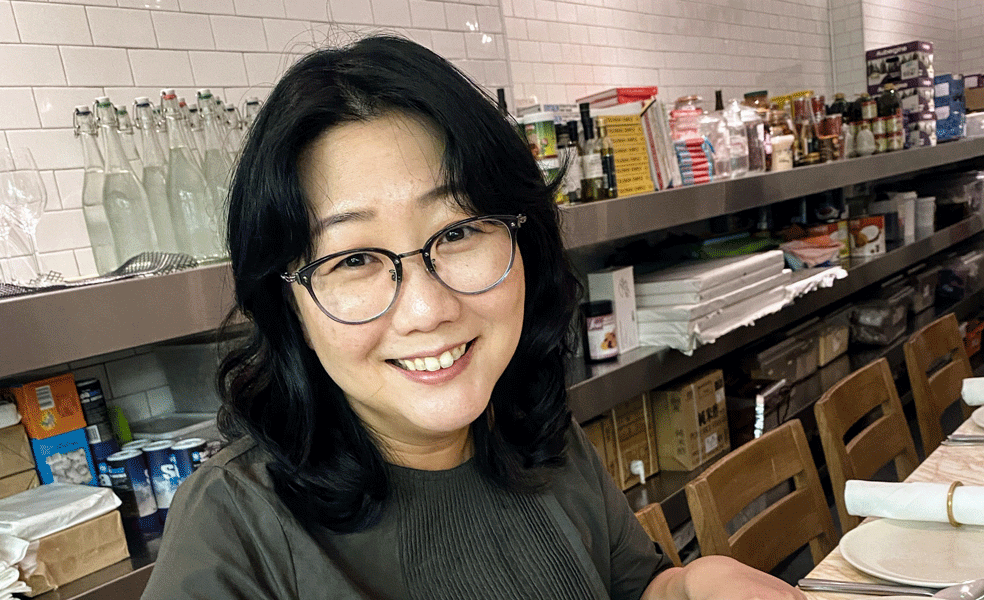

Today, Park once again lives in the U.S., and she is a Core Faculty in Antioch University’s School of Education. She’s still grappling with the ways that the American education system treats students from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Her classes at Antioch deal with the political and historical context of schooling in this country and the implications for teachers who want to be social justice educators. She teaches electives on topics like multiculturalism, anti-racism, globalization, and immigration. But her work also includes social and emotional learning, the process by which people learn healthy development and relationships. She brings her whole personal story—from being a child between cultures to her experiences as an early childhood educator—to this subject.

Noticing Cultural Dynamics in the Classroom

In her education as a Montessori teacher and her work as an early childhood educator, she gradually started to notice a pattern in how her students were treated by other teachers and the larger system. Dominant cultural norms were being imposed on children from non-dominant cultural backgrounds. As she explains, the white teachers were “swimming in their own pools,” unaware of how their cultural biases affected their students.

One thing she noticed, which disturbed her deeply, was “the way that educators talk about particularly Black and Brown boys, kind of the discourse of them not having good self-regulation.” This really bothered her, and she didn’t understand it. She felt that these children were not being given the same opportunities as their white peers, and were being disciplined or evaluated negatively based on white cultural expectations.

Some specific examples of these dominant cultural expectations were that a child should sit still, that only one person should talk at a time, or that if you are moving your body that means you aren’t listening. Having a bicultural background herself, she took on the responsibility of educating her white peers about how cultural norms affect our expectations of students.

This experience led her to the realization that the powerful concept of social and emotional learning needed to be combined with cultural awareness if it wasn’t going to perpetuate harm. Empowered to make a change, she advocated for staff development time to be focused on people understanding their own cultures. However, the newer white teachers didn’t see themselves as having a culture, so it was hard to break it down and talk about it.

Bringing Social-Emotional Learning Standards Forward

The level of cultural awareness in adults continues to be a challenge in social-emotional learning. Park was a member of the state workgroup that helped Washington State officially adopt the standards, benchmarks, and indicators of social and emotional learning. In 2020, alongside the pandemic, Washington public schools were required to teach these skills. Adult teachers need to have some awareness of what these standards are in order to create learning environments that support social and emotional development. With the pandemic in full swing, teachers needed social, emotional, and mental health support as well.

Currently, Park is working with the Social Emotional Learning Advisory Committee to work toward promoting and supporting social and emotional learning in Washinton State. Some teachers might push back on this because they don’t think they need these standards for every single class. For example, a math teacher might think that they don’t need to teach social and emotional learning, but what happens when a student is working on a difficult set of questions and becomes dysregulated? Park believes that all teachers need to have the language and skills to support students throughout their school day. To teach students, teachers must do the inner work to be able to model these skills while providing students with opportunities to practice them.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, countless teachers and administrators across the U.S. learned about the concept of social and emotional learning, and it even became a buzzword. This enthusiasm, says Park, is great, and she’s happy to see it carried forward. And it’s a natural response to the pandemic, when many elementary school children were, as Park puts it, “just sitting in a room by themselves for two years.” Social-emotional learning can’t be practiced alone; you need real conflicts and situations to learn these skills. When we wear masks and the human face is mostly covered, kids are not receiving the nonverbal feedback to read, register, and monitor the emotions and social cues of others. As we have been coming out of isolation, Park sees a greater need for social and emotional learning than ever.

If more children had these skills, they would be able to develop the emotional sturdiness to take care of themselves and others explains Park. This sturdiness is cultivated through experiencing failure and learning that it’s not going to break you– it’s an opportunity to get better at what you are doing. Social and emotional learning not only teaches kids to be more resilient, but it also ingrains in them that emotions are healthy—and not something that must be avoided.

Healthy relationships between students and teachers allow educators to address each student individually because they know the children well. Teachers ideally know what their student’s behavior is communicating. For example, if the child is unable to sit still, is it because they are tired, or are they a child who needs a periodic movement break? Is the assignment engaging and culturally relevant? According to Park, instead of trying to fix the child, a teacher should look at what isn’t working in the learning environment.

The Importance of Cultural Awareness in This Work

With the widespread adoption of social and emotional learning as a framework, Park has seen many problems arise when these concepts are applied without centering equity and cultural responsiveness. Park has long looked up to Dena Simmons, a leader in transformative social-emotional learning. In her 2015 TED talk on the subject, Simmons says, “There is emotional damage done when young people can’t be themselves when they are forced to edit who they are in order to be acceptable; it’s a kind of violence.” In this speech, Simmons tells a story from her own childhood of a well-meaning teacher who corrected her speech and taught her to enunciate certain words. While this teacher was probably well-meaning, the only thing this taught Simmons was that she didn’t belong there. Park credits Simmons for the sentiment that social-emotional learning without the equity frame is like “white supremacy with a hug.”

Park can give endless examples of situations in which a child is given special opportunities that are conditional on behavior—for example, being invited to be part of the higher math group or getting to participate in the school play. “The child’s behaviors and the labeling and pathologizing of those behaviors often deny them opportunities,” Park says. “And when we have to explain those things and cross a cultural divide to do that, it’s often that the weight of the burden falls on the child.” As she sees it, some educators are rewarding children for adhering to cultural norms, looking to that as the sign that they’re ready to progress to the next thing, even though adherence to cultural norms should not be the measure of their brilliance.

It is this experience that informs her choices as an educator at Antioch today. She hopes to continue to increase awareness in education on the issues that face culturally and linguistically diverse students and to help teachers support them in sustaining their identities. “The social and emotional learning piece and the equity piece must go together, do not do them in isolation, or you will be harming kids,” Park says. “And adults must do their own work; they must seek opportunities to build their own social-emotional capacities in order to support children.”