In 2018, Antioch New England faculty member Kayla Cranston led AmeriCorps VISTA members in a project at the Saint Louis Zoo, in Missouri. “We aimed to identify which conservation programming would be most relevant, valuable, and useful to members of the community that the zoo had historically underserved near Ferguson, Missouri,” explains Cranston. This emphasis on including in their design process the largely Black residents of Ferguson, a town that had seen many protests after the 2014 murder of Michael Brown, marked a new emphasis for the zoo. And for Cranston, it was a powerful opportunity to implement a process she created called Co-Designing Conservation With (Not For) the Community. (She gave a presentation on it last year.) The project was a great success.

Today, Cranston is expanding on this work, directing an exciting, cross-campus project called the Co-Designing Conservation Partnership. In this work, Antioch faculty and graduate fellows are partnered with AmeriCorps VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America) members—then, as teams, they work with zoos and aquariums across the US. The overarching goal is to work with local historically marginalized communities to co-create new conservation programming.

The key concept is contained in this word, “with.” In each of these projects, the Americorps VISTA members are recruited from the communities that the project intends to engage. This is one of the ways in which the method of “Co-Design” takes a radical approach: rather than merely gathering data about a community, conducting research, or holding passive listening sessions, the project seeks direct and authentic conversation with community members. They believe that this will produce a more effective and long-lasting result.

The early success of these endeavors is exactly what led AmeriCorps VISTA to ask Cranston to scale up her model. The Co-Designing Conservation Partnership is the current result, and it has spread across Antioch New England, Antioch Seattle, and three zoos—the Cleveland Metroparks Zoo in Ohio, Zoo New England in Boston, and Woodland Park Zoo in Seattle. In the next few years, as more zoos and aquariums are accredited, the project intends to expand, with an eye toward Southern California, where Antioch Los Angeles and Santa Barbara could serve as key base stations.

Recruiting AmeriCorps Members from the Neighborhood

AmeriCorps VISTA is one of three major AmeriCorps programs—and like the others, it is funded by the Corporation for National and Community Service, an independent federal agency. VISTA is unique in that it specifically centers around anti-poverty work. In general, it recruits members to do activities such as fundraising, grant writing, research, and volunteer recruitment. VISTA is a professionalizing experience. Members are prepared for all kinds of public service and nonprofit jobs. It’s also an opportunity to do meaningful work within a community.

The Co-Designing Conservation Partnership project takes VISTA and makes the service more specific through targeted recruiting: once a community that the zoo or aquarium has historically underserved is identified in the surrounding area, the next step is to work to recruit VISTA members from that community. In Cranston’s original Saint Louis project, four VISTA members were recruited. Of those four, two had been born in the communities surrounding Ferguson, the other two had lived there for at least a decade.

These VISTA members act as a bridge to the community. “The reason this is so important,” says Cranston, “is if you are working with a program that is going to require long-term engagement from the community, you want to have them own the project in some way. And that’s easier to do when they see somebody who looks like them—and has a similar background to them—in the driver’s seat.” With the local VISTA members running the project on the ground, communities are less likely to experience unilateral decision-making or to feel like they are part of a disinterested study run by an external organization.

In Ferguson, the VISTA members were essential to building trust with the communities there. They also gave Cranston and the Saint Louis Zoo a more authentic perspective of local views, and by participating in decision-making, those views were empowered by design.

This same model is being used in the current work. Three VISTA members were recruited for each area—Seattle, Boston, and Cleveland. (These zoos are each accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, which means they uphold strict animal welfare standards, aligning them with the mission of conservation.) The VISTA members they have recruited are integral to the teams they serve with. As Cranston explains, “We bring these folks to be literally at the table with us every single day, forty hours a week, for three years, to help us shape the process by which we go about engaging their fellow community members.”

Co-Creating a Sustainable Community Relationship

The Co-Designing Conservation Partnership is a three-year process, split into three “phases.”

The first phase is to identify strengths that already exist in the community. What existing organizations are already providing quality services? Where are there opportunities to build upon those strengths towards the future goals residents have for their community? In the second phase, conservation programming is strategically designed in collaboration with local organizations with which the zoo built relationships throughout the first phase. The third phase is the pilot implementation of this programming.

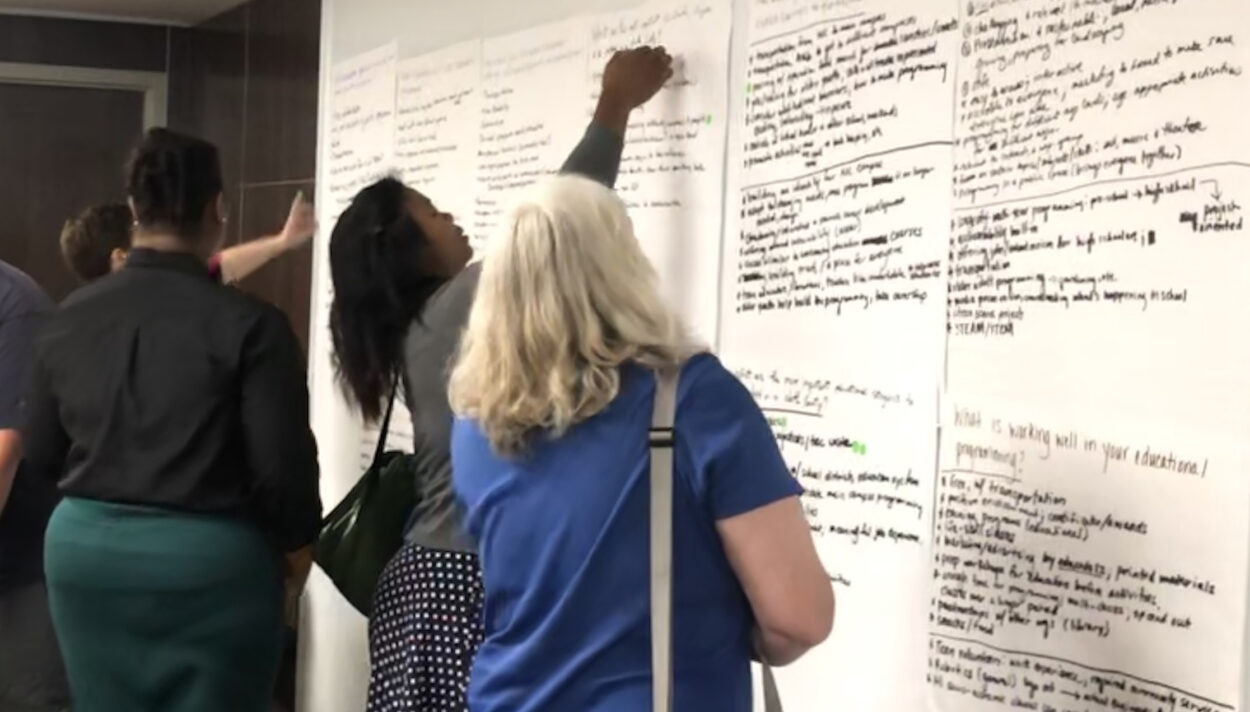

These phases can be seen in the project in Ferguson. In the early stages when Antioch and Zoo partners were not necessarily known or trusted, gathering information meant going into the community. Cranston is emphatic about the importance of doing this. She explains that in Saint Louis, “Instead of asking them to come to us, we went to their community meetings, we went to neighborhood association meetings, church meetings. Our VISTAS were out there beating the street.” Saint Louis Zoo staff and VISTA members learned about the community within its own institutions first. Then, after extensive participation in Ferguson community meetings they were invited to by the community, they extended their own invitations to residents to participate in surveys, focus groups, and listening sessions. These were conducted at locations within the communities surrounding Ferguson, such as schools and community centers.

Throughout all three phases, Antioch and the Saint Louis Zoo reflected back to the communities what they thought they heard. And this model is the one being carried forward. This sets up the structure for continued dialogue on program development and holding the resulting programming and processes of engagement up to the standard the community set for them in the first year. All of these steps are based on dialogue between Antioch staff, the zoos, VISTA members, and the community.

Cranston has designed the program this way not just through intuition and trial-and-error but also because of her deep familiarity with cutting-edge research on the process of communicating and motivating pro-environmental behavior change. At Antioch, Cranston serves as the director of Conservation Psychology Strategy & Integration. Historically, she explains, many cultural and conservation organizations have been yoked by “colonialistic systems.” She is determined to move away from this power dynamic. As Cranston explains, this means “intentionally creating a structure for equitable dialogue…and defining what a lasting partnership can look like.” Through doing this, the zoos learn how to become better neighbors, and they develop strong skills to serve and listen to their communities far into the future.

The Benefits of Co-Designing Conservation—Teamwork

Beyond being the Co-Designing Conservation Partnership’s project director, Cranston also serves as the program’s faculty lead at the Antioch New England campus. This means she is leading VISTA members and Antioch staff working with Cleveland Metropark Zoo and Zoo New England in Boston.

Other faculty partners at Antioch New England—including Meaghan Guckian, Jean Kayira, Libby McCann, and Abigail Abrash Walton—have been instrumental in expanding the project. Abrash Walton finds the work exciting and important, explaining, “The Co-Designing Conservation initiative exemplifies the cutting edge of what the field of Environmental Studies and Sciences needs to be doing, which is really thinking about how to create belonging, how to create inclusiveness, how to build up historically marginalized communities.”

Meanwhile, the faculty lead at Antioch Seattle is Sue Byers. Byers is working with local VISTA members and Woodland Park Zoo. She is particularly interested in how the project can inform and intertwine with the MAEd in Urban Environmental Education, which she directs.

A Mission of Meeting Many Needs

Beyond sustainable relationship-building, another goal of the Co-Designing Conservation Partnership project is to produce conservation programming. Sometimes it’s something already offered that the zoo can readily provide. In this case, the program’s benefit is that it results in a structure where this is effectively communicated to the community it serves. For instance, some zoos will bring animals into classrooms by request—but the school might not know that this programs exists.

Other times, the possibilities for collaboration are more surprising. This is where the project excels.

In Saint Louis, for example, Cranston expected the community to want more K-12 school programming. Instead, the community asked for green job skills. It turned out that the Saint Louis Zoo already had facility staff who knew how to install solar panels, permaculture beds, compost beds, etc. The skills and the desire were perfectly matched. But the Saint Louis Zoo didn’t have a way of training young adults. It hadn’t been thought of as possible.

Cranston explains what happened next: “What we ended up doing throughout that second year was developing a relationship with a local workforce development organization that had gotten really high stars from the community, and all of a sudden we had that partnership that allowed for us to develop a green job training program.” Without the Co-Designing method, they wouldn’t have known how to implement this green jobs program, but more importantly, they wouldn’t have known that it was something the community wanted in the first place.

The core mission is to build lasting, justice-oriented relationships between historically marginalized communities and nearby organizations. These relationships can then authentically produce conservation programming that serves the local community in ways that are relevant and useful to them. This is the work being done by Cranston, Byers, and their VISTA members. It’s designed and ready to be spread to other campuses across the country. As Cranston says, “The ultimate goal is to help a national network of conservation organizations move … toward a true allyship. [To help us move] toward the equally important goals of community wellbeing and wildlife conservation.”