“The question now is, how do we do this?” says Antioch University faculty member Dr. Kayla Cranston. Cranston is leading Antioch’s ongoing Co-Designing Conservation With (Not For) Communities project through which the university partners with zoos and aquariums across the country to help these public institutions promote communication and develop programming in close consultation with local, historically marginalized communities. “Because,” says Cranston, “it turns out that’s just not happening right now on its own.”

When the project first began in the spring of 2021, its activities consisted largely of recruiting AmeriCorps members to work on the project and creating lists of community resources for the participating zoos. It launched at Zoo New England in Boston, Cleveland Metroparks Zoo in Ohio, and Woodland Park Zoo in Seattle.

At the end of its first year, the project has seen many advances, and it has generated powerful questions—and reams of data. “At least a full year of data needs to be analyzed,” explains Cranston. At the same time as the project reflects on its work, it’s also pressing forward and opening collaborations with three additional zoos.

Over the last year, Cranston and her team have engaged the communities around the partner zoos in ways that highlight what is working—and locate community aspirations for the future. Ultimately, she is finding that the Co-Designing approach offers a powerful new framework to listen and make an impact with partner communities.

Engaging Community to Identifying Assets

Cranston began forming her team by recruiting AmeriCorp VISTA members from the communities surrounding each zoo site in Boston, Cleveland, and Seattle. These Americorp members conducted outreach and brought their own knowledge to create detailed lists of community leaders, service providers, and institutions. This list of stakeholders is being used as a starting point for identifying goals and who to engage further in the process.

This first phase, which the team calls “Identify Assets,” began in fall 2020. Cranston says, “It took a really long time to identify the stakeholders, and it’s really important for it to take that long.” The process had to be done through community outreach, which is where the VISTA members came in. Sage Mack, a VISTA member who works out of Cleveland, Ohio, recalls a typical day during this stage. “I’d call different organizations and tell them about the project. We made a list and lots of spreadsheets,” she says. “I also did a lot of walking in the community. People in Cleveland really liked the Zoo, so that made it easy.”

Once lists of stakeholders were generated, the organizers gave surveys and gathered focus groups, where they asked participants key questions about what kind of programming the Zoo could provide. They also asked residents of the community for their guidance. This was encapsulated in three major questions: What is already working in your community? What are the community goals that you have for your community for the next five to ten years? And what can we design together to reach those goals?

“These three questions are the essence and the basic element of what Co-Design is about,” says Cranston. The questions were fruitful, which has created a lot of exciting work. Says Cranston, “Our analysis team at Antioch New England is now doing a roll-up of all of that data and putting it together in a way that will be helpful for the zoos and shared back with the communities.”

Putting this data together is more complicated than it might seem. Most of the data comes to Antioch’s New England campus as transcripts from focus groups. Cranston is careful to center people, taking a resident-first approach. As Cranston explains, “We use what we found from the residents to ask questions of the service providers. And then we jam all of that together. And we do the hard work of finding some middle ground.” It’s hard work because sometimes the people empowered to make decisions through having a “stake” in the community don’t share a perspective with the actual residents that the Co-Design programming is hoping to engage in decision-making.

Creating a Way to Listen

The original incarnation of the Co-Designing Conservation project took place at the Saint Louis Zoo in Missouri, where Cranston’s goal was to help the zoo better serve the historically marginalized, majority-Black community in the nearby neighborhood of Ferguson. As she explains, “In Ferguson, what we found out is that it is not always the case that service providers want the same thing as residents.” The biggest difference was between educators—service providers—and parents. The educators were often more focused on higher test scores, so they wanted STEM programming. The parents, concerned with economic survival, wanted more job readiness programs. Cranston is watchful for this kind of disconnect in data from the current sites. As she says, “It’s important to keep those opinions separate and be able to join them together in a way that meets both goals.”

Cranston and her team frame the questions around what’s working, rather than what’s not. This is called an asset-based approach, which is different from how people in marginalized communities are usually engaged. “The quickest way to halt conversation with communities that have been historically marginalized, in my experience, is starting with a question about lack or deficits or needs,” Cranston says “This is the traditional way of doing community engagement that I have seen go wrong.” Cranston is fundamentally devoted to creating an environment of listening that doesn’t reinforce the biases of power.

These asset-based questions are designed in such a way that they don’t elicit shame or discourage answers that admit need. People get tired of talking about what they don’t have, so in these conversations, professionals who aren’t directly impacted often have an easier time speaking up. This means that people who have ideas about what the community needs but don’t live in the community may become the dominant voices. “We ask how we can be better neighbors by listening to what the community’s aspirations are,” says Cranston. Ultimately, she does this “so that we can work together to reach those goals while at the same time conserving wildlife.”

Americorp Opportunities and Experience

This culmination of the past year’s data-gathering also marks a moment of change for the AmeriCorps Vista members. Every year, these members doing national service can choose, if they want, to sign up again. While some are continuing with AmeriCorps and Antioch, others, enriched by the experience and the robust professional network generated by the project, have taken new positions in related fields.

“I’ve learned a lot,” says Mack. “I think the difference I noticed is instead of bringing food to people, you map out how to create a food program. You know: it’s a bigger picture.” For them, working with the Co-Designing Conservation project has created an inspirational sense of scale and institutional efficacy. This is in line with the spirit of Co-Design, which rigorously holds back from directly declaring what a community needs and instead tries to find a way to listen.

Working with Antioch on the Co-Design project, which involves academic research, is uniquely professionalizing. Although Mack is leaving the project to focus on a Bachelor of Arts in Global Studies and further work in AmeriCorps, they see the value of the experience. As they say, “I feel like they gave me a formula that I can work with throughout my life.” Through the project, Mack got to act within institutional forces and practice change on a design level. “Also,” says Mack, “I learned that I love animals more than I ever thought.”

Community Mapping and Next Steps

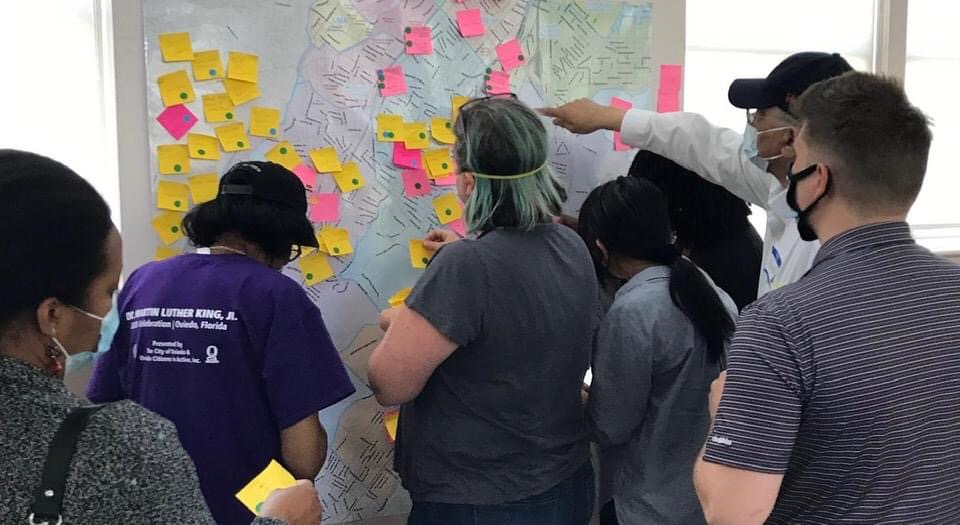

In May, Cranston started bringing the opinions of residents and stakeholders, combined into a useful middle ground of community goals, back to everyone who has participated in these conversations. “We ask them to help us do two things: help us identify what success would look like if these programs worked, and show us where these programs already exist in the community,” Cranston says. This is called “participatory asset mapping.” In this mapping project, helpful programs and services are marked physically on maps of the community, by community members. This is how the project learns about deficits and needs without framing it as a “lack.” As Cranston says, “Without even asking, ‘Where are things lacking,’ we have this map with dots where things are going well. So we can also see where there is room for growth.” Cranston describes this as “growing the edges.”These “edges” on the map—where services are lacking—indicate the type of programming that Antioch and the Zoo should try to design.

In May, Cranston started bringing the opinions of residents and stakeholders, combined into a useful middle ground of community goals, back to everyone who has participated in these conversations. “We ask them to help us do two things: help us identify what success would look like if these programs worked, and show us where these programs already exist in the community,” Cranston says. This is called “participatory asset mapping.” In this mapping project, helpful programs and services are marked physically on maps of the community, by community members. This is how the project learns about deficits and needs without framing it as a “lack.” As Cranston says, “Without even asking, ‘Where are things lacking,’ we have this map with dots where things are going well. So we can also see where there is room for growth.” Cranston describes this as “growing the edges.”These “edges” on the map—where services are lacking—indicate the type of programming that Antioch and the Zoo should try to design.

Despite the busyness of impending asset mapping, Cranston looks forward to the next phase, “Strategic Planning,” which began in July. So far, the general themes derived from the data have been daunting: affordability, housing, infrastructure stability, and community wellness have all been consistently raised as possible “edges.”

As Cranston says, “These issues are so big, but the reality is we’re designing programming the Zoos can contribute to. How do we help to alleviate some of these bigger issues?” Cranston laughs. “How in the world do we even go about it?”

This is the purpose of Strategic Planning, which takes a full year. “We’re not just trying to put hedgehogs in the classroom,” says Cranston. Armed with data from community mapping, the project will set out to design programming that tries in some way to address the larger forces of marginalization, all while promoting an ethic of conservation and reminding residents of how relevant their Zoo can be to their real lives.

And even as the current Zoos move forward with their community engagement, Cranston has taken steps to expand the project. They’ve added on a new site in Rhode Island: Roger Williams Park Zoo. And in November, Zoo Atlanta in Georgia and Detroit Zoo in Michigan will also begin conservation partnerships with their communities. These new sites are being brought on under the Conservation Psychology Institute at Antioch University’s New England campus. Cranston, her team, and the participating zoos hope that with this expansion, their work will benefit hundreds of thousands more people.

For more about the co-design process, read a peer-reviewed article Cranston co-authored with Wei Ying Wong, Shareen Knowlton, Curtis Bennett, and student Shannen Rivadeneira online here. This article will be published with many others in the Conservation Psychology special issue of Zoo Biology that Kathayoon Khalil and Cranston are editing in October 2022.