Have you ever had a moment when your perspective underwent a profound shift, revealing a new way of experiencing and understanding your surroundings?

For Owen George, that pivotal moment occurred during their undergraduate years at Colby College in Maine, when they found themselves captivated by the way their fellow students talked about gender and identity. They were an international student and had already lived in several different countries, but before this they had never felt comfortable openly discussing—and exploring—their queer and trans identities. “There was a whole aspect of my life that had been hidden away,” they explain. Soon they were exploring their identity not just through informal conversations but also by taking gender studies classes and exploring the writing of queer theorists.

Today, Owen sees their identity as central to their intellectual life and work in the world. It has led them to shift from studying marine conservation towards environmental justice, and it’s played a big role in their decision to pursue graduate education. And it’s a big part of why they chose to enroll in Antioch’s Master of Science in Environmental Studies in New England, where they are finding a supportive environment for their work bringing queer theory into the field of environmental studies.

Vindicating the rightness of the path they’re on, Owen recently received the Ginsberg/Wessels Scholarship, which is annually awarded to one Environmental Studies student who displays academic excellence and true leadership. And they recently published the essay “Climate Solutions Need Queerness” in YES!Magazine. In a lot of ways they are just getting started in their work of bringing together queer theory and environmental studies, but already their story is a testament to the transformative power of education and self-knowledge to empower us towards action and greater understanding.

Owen arrived on the Colby campus in 2017 fresh from high school in Switzerland, where they had excelled academically despite facing many social challenges. Their schooling had been notably devoid of discussions about queer identities, an omission that became starkly apparent as they now joined vibrant dialogues about gender and sexuality. These were accompanied by small yet significant gestures that left a lasting impact. “There were casual details, like pride flags in common rooms and sharing your pronouns,” Owen explains.

Owen was one of those rare undergraduate students who arrived at a liberal arts campus knowing exactly what they wanted to study: marine conservation. Their childhood had been filled with camping and long hikes, fostering a love of spending time outdoors that led Owen to think that a career in conservation would be satisfying and meaningful. But their widening sense of possibility began leading their intellectual interests in a somewhat different direction.

This, they say, arose due to “the combination of the pandemic, which limited lab classes, and my understanding of my queer identities, coming out, and transitioning.” By their junior and senior years, says Owen, “I became more interested in environmental policy and also started taking courses in gender studies.”

On a trip back to Switzerland in 2020, Owen experienced how identity bears on perspective, influencing what we notice and the questions we ask. Walking to their favorite vegan donut shop, Owen was surprised and impressed to see Pride and Trans flags alongside Black Lives Matter banners in windows. Owen still wonders if Switzerland had evolved while they were gone—or if, by embracing their identities, they had changed how they perceived their environment. Owen thinks it is probably a combination of the two.

“I feel like now I go through the world with a much different perspective than I did before I came out, when I didn’t really know what joy was,” says Owen. “I feel like I need to go back and experience all of the places I’ve traveled to, because I didn’t fully experience them when I went there the first time.”

The shift in Owen’s perspective that helped them get in touch with their identity, experience joy, and embrace change now underpins the research and inquiries Owen is engaged in at Antioch. They are using the program to explore what happens when science and environmental studies are approached through a gender studies framework.

One of the first courses they took at Antioch was “Essentials of Advocacy,” taught by Abigail Abrash Walton. This experience confirmed for Owen that finding points of confluence between environmental and gender studies wasn’t just possible at Antioch—it was encouraged. So Owen began approaching the questions posed by their coursework in a more personal way, bringing their own idiosyncratic interests and lived experiences to bear, which led to research on everything from the misperceptions of trans athletes to a deep dive into the world of queer ecology.

More recently, in the class “Justice, Equity, and the Environment” taught by Sarika Tandon, Owen began thinking about questions like, Should queer ecology be at the foundation of climate justice and advocacy? Why might it be powerful to approach thinking climate solutions through a framework of queer theory? What can social justice movements teach the environmental movement about organizing and resilience?

In their term paper for that class, Owen tried to work out some of their answers to these questions. “Queer ecology,” they wrote, “embraces the plurality and paradox of nature, rather than forcing it into the binaries and categories that our society craves.” Owen reminded readers that people come from the same evolutionary fabric as caterpillars that undergo metamorphosis, transitioning into butterflies. They noted that reef fish that change sexes are celebrated for adapting to the needs of their environment. Additionally, most flowering plants have male and female functions present in each blossom, and their flowers are labeled “perfect.” Fluidity, change, and transformation constitute nature, and humans are as much a part of nature as the 1,500 species that engage in same-sex behavior.

After reading Owen’s essay, Tandon felt that a broader audience would benefit from their insights, so she encouraged Owen to consider publishing the piece. “I was struck by the importance of Owen’s work and their beautiful writing in their final paper,” says Tandon. “As someone who works in the field of climate equity, I could see that this writing was making a significant contribution to the field. I really wanted to see this thinking shared out in wider circles in the hopes that Owen’s insights could inform others and elevate the conversation about queer ecology in the climate field.”

Tandon later shared the essay with her own faculty mentor, Owen’s academic advisor, and Advocacy for Social Justice and Sustainability Concentration director Abigail Abrash Walton. “My first thought,” said Abrash Walton, “was that Owen should submit the piece to YES! Magazine, a publication focused on solutions journalism.”

Owen did submit the essay, and in June of last year the magazine published “Climate Solutions Need Queerness.”

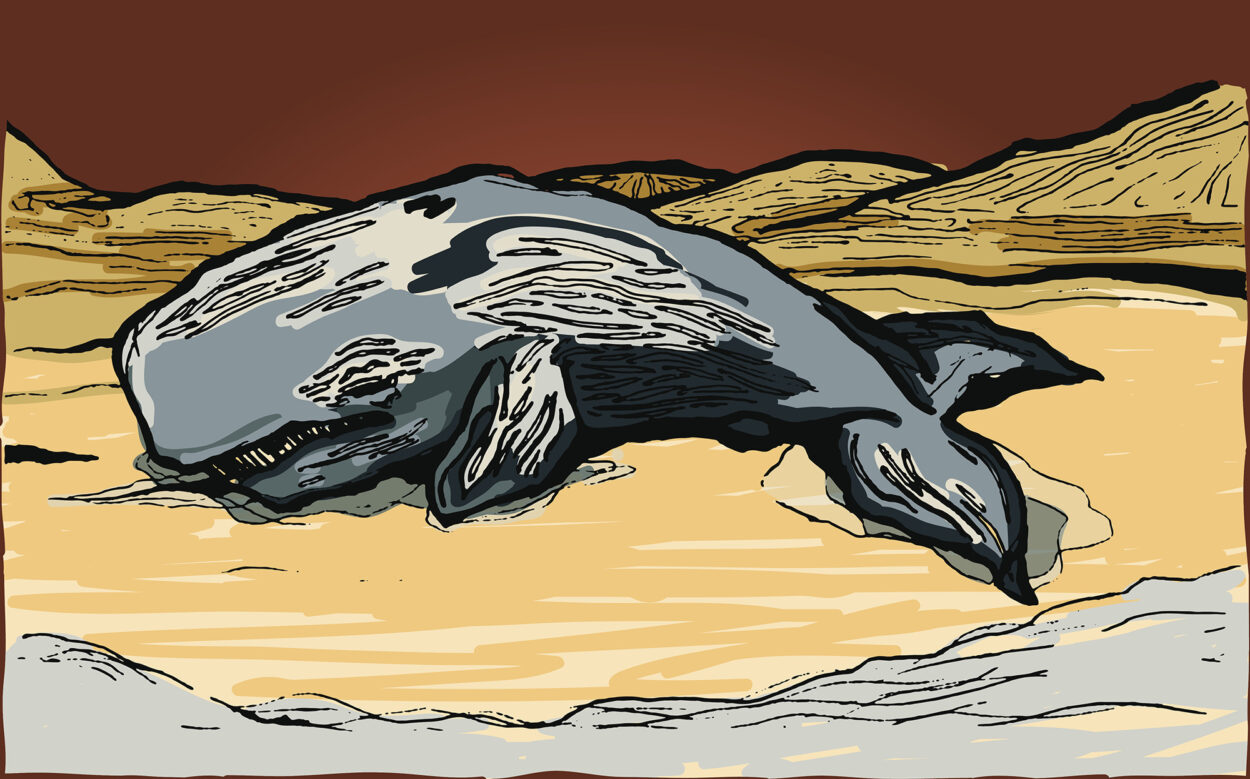

When a whale dies, its body will often settle on the ocean floor. While the life of the whale is over, this is far from an ending: instead, the whale’s carcass becomes a center of life, engendering and sustaining a complex ecosystem of living organisms, becoming a site of rich nutrients that can provide sustenance for decades. Known as a “whale fall,” this process is a key mechanism to sustaining biodiversity on the ocean floor.

Owen draws a parallel between a whale fall and activists who continue to sustain the fight for social and environmental justice. They point to the legacies of people like Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson whose actions continue to nurture and sustain social justice movements long after their deaths. The amount of life they generate speaks to the magnitude of their actions and ideas.

At the same time, questions of trans identity and whether trans people are allowed to have civil rights in America are finding hostile answers in many states today. Owen is quick to acknowledge the raging fires—both politically and environmentally—that threaten the well-being of communities that are actively working to create spaces where differences can thrive. “My group of friends and I in our three-block radius are doing great, but we just need to step outside a little bit,” says Owen. “That’s uncomfortable, and yes, it’s unsafe, but that’s how we make change happen.”

In acknowledging discomfort as part of the process of change, Owen has found new ways to give breadth to their activism and advocacy—by committing to what brings them joy. This means not only spending time in the outdoors but also embracing their identity as a trans athlete and competing in local CrossFit competitions. “Queer joy is such a beautiful form of resistance,” they explain. “It’s like you’re just living your life, and by doing that, you’re saying f*ck you to all the systems that don’t want you to be having fun.”

In this as in so many ways, Owen is expanding the broader cultural imagination of who exists in our environments and how we conceptualize our relationship with place. And they are continuing to push forward in their thinking about how environmental and social justice can build off each other. With their recent publication in YES!Magazine and being awarded the Ginsberg/Wessels Scholarship, it’s clear that they are finding their voice as a scholar and activist.

“It’s an honor to see my academic work being recognized at such a high level,” says Owen. “Most of my work during my time at Antioch thus far is about the queer liberation movement and its intersections with the climate movement, a nuanced overlap that is still relatively unexplored. Receiving this award gives me confidence and encouragement to continue to pursue research in this area where my passions, personal and professional experience, and academic interests meet synergistically.”

Note: this article has been updated to more accurately capture the sequence of events that led to Owen publishing their essay.