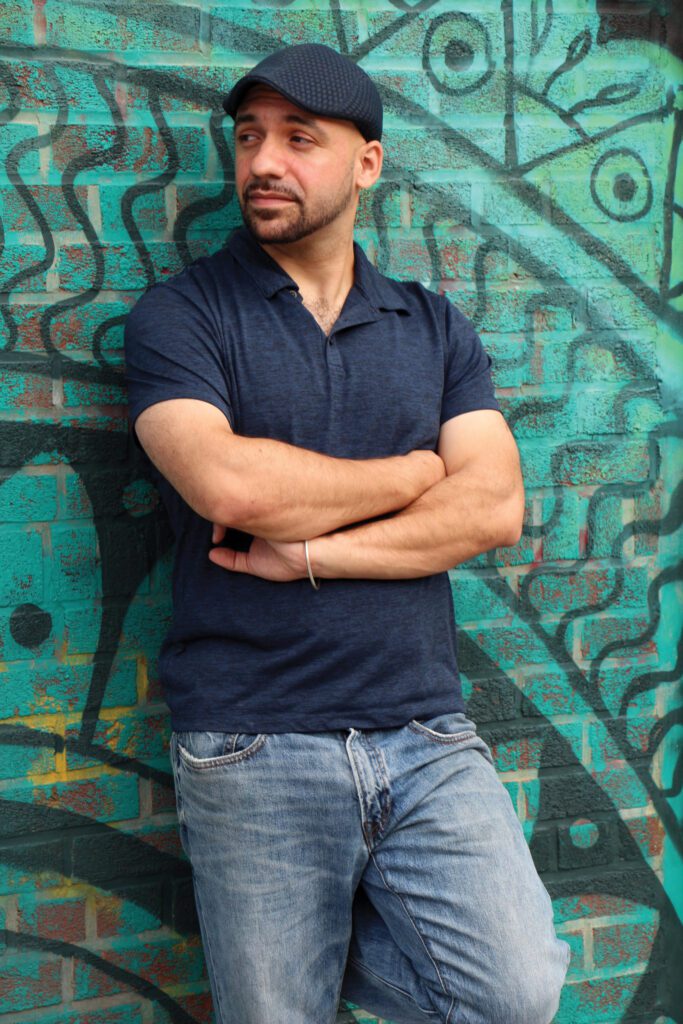

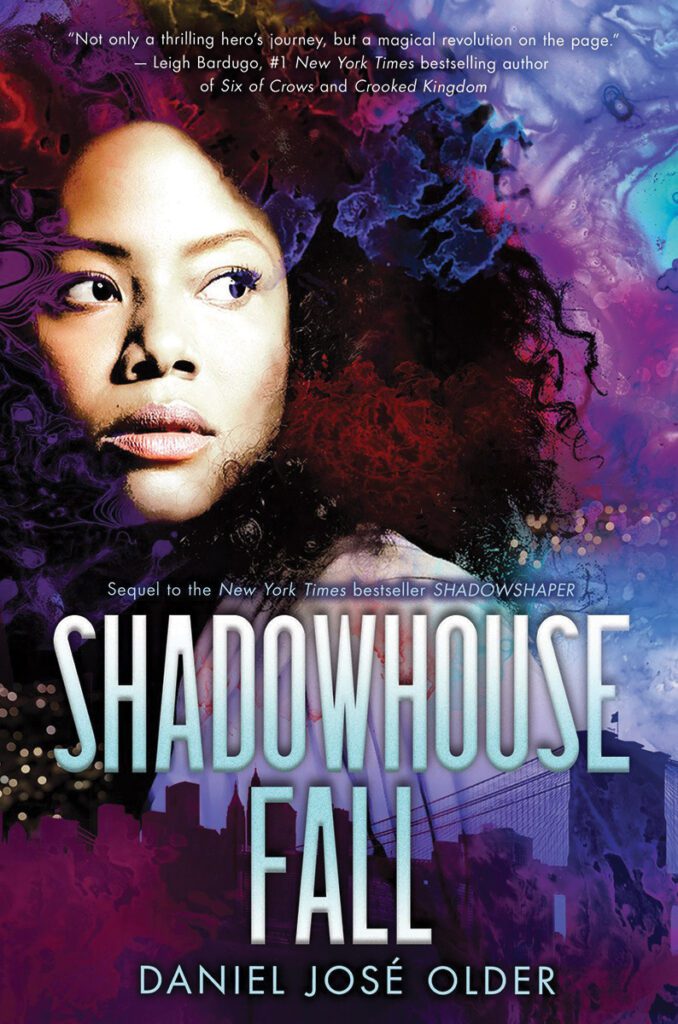

Daniel José Older ’13 is the New York Times bestselling author of Last Shot (Star Wars): A Han and Lando Novel, the young adult series The Shadowshaper Cypher, the Bone Street Rumba urban fantasy series, and the middle-grade historical fantasy Dactyl Hill Squad. He won the International Latino Book Award in 2016. Shadowshaper was named one of Esquire’s 80 Books Every Person Should Read.

You were a paramedic in New York City, a bike messenger in San Francisco, a teacher, a waiter, and more. How have these jobs shaped who you are?

This brings up the argument or dispute about how much we read and how much we live as writers. I think there’s one idea that we should always be reading when we’re not writing. I’m a huge advocate of living—not at the expense of reading, but I just don’t think our education emphasizes enough the power of experiencing things.

Being a bike messenger, a paramedic, and a community organizer, all made me a better writer—being able to see the city from so many different sides (class, race, etc.). You have to understand race, gender, and power in order to negotiate the world and to maneuver the world of publishing because it’s so messed up on so many levels.

When you went back to get a low-residency MFA at Antioch, what were some of the things you learned?

One of the main things I learned is that I can do it. I was working full time like most people in the program and I was editing an anthology while I was there too. It was one of those situations where you have to really want it and I really did. That taught me that I could pull that off. I had never done that amount of work before.

And of course, I had great teachers. Tananarive Due changed my life. Antioch’s program really jumped out to me because of the really cool political slant, community involvement, and Tananarive was the clincher because I loved her work so much. She was really giving with her wisdom, was so sharp with her analysis, and so brilliant with her critiques and comments, as well as her advice about publishing and the larger world.

As a cool side note, the book that I worked on while I was at Antioch just got sold last week. It’s called The Book of Lost Saints.

That’s so exciting! When is it coming out?

It comes out next year. It’s a departure for me because it’s a straight contemporary novel. It’s fantastical to some extent because it’s narrated by a spirit, but it’s very much about life.

People think it’s so easy to get published, but we all know how untrue that is.

It’s a hustle. And it’s still a hustle. I try and tell students this and let people know that we have this idea that at a certain level, you can do whatever you want, but I get rejections plenty of times still. Shadowshaper was rejected 40 times by agents and that was before We Need Diverse Books and before the publishing industry realized characters of color can in fact sell.

I want to talk about We Need Diverse Books in a second. But I want to know more about your family background—where are your parents from, what they are like, was storytelling a part of your childhood?

I come from a Cuban and a Jewish family. My mom is Cuban and my dad is Jewish and from Baltimore. My mom immigrated to this country when she was 16. I grew up surrounded by books and storytelling on both sides. My family loves movies, music, and just appreciates the arts all around. That’s the best gift for a kid. My sister is a writer too—she has a sci-fi trilogy out too. Her name is Malka Older. She’s an amazing writer.

Your mom and dad are from different places and are from different cultures—did that shape your view of the world?

A lot of these questions I dealt with in Half-Resurrection Blues and the whole series, A Bone Street Rumba and this is about a character named Carlos who is half-dead and half-alive. That was definitely a not-too-subtle way of looking into being of multiple cultures, moving through the world and being accepted and rejected by certain people. And him sort of dealing with the question of being mixed and of being of two worlds. Most of his friends are ghosts and then he has living friends and he’s always trying to negotiate that harmony and dis-harmony.

As a poet, I grew up in a world where people of color (POC) haven’t really had a strong history of publishing and if there were POC, it might be one. But in the last bunch of years, things have changed. The children’s field seems to have progressed a little more slowly in that We Need Diverse Books initially became simply having white writers paint in or write characters of color. What are your thoughts and experiences with the publishing field across your writing life?

There are two pieces I’ve written that I want to point you to. One is called “Diversity is Not Enough: Race, Power, Publishing” and another is “12 Fundamentals of Writing ‘The Other’ (And The Self)” and both were on BuzzFeed. The movement was started by women of color writers and they’ve always been clear that stories need to come from the community that they’re about and you’re very right that publishing has tiptoed around that idea and tried to fill a quota. White writers writing characters of color is a very real thing. I think ultimately, it’s never been about, you can’t write that character, but it’s about the fact that we demand that you do it right. And now that we have a voice, well, these demands have always been there, but there’s social media now and it’s a platform where people now have a voice of power and that’s incredible. That’s really changed the world and made it very uncomfortable. What you see is backlash and other things and people saying this is a lynch mob and a witch hunt—the same response you see to the #MeToo movement, when people are speaking truth to power.

I think it’s an exciting time to be a writer and it’s amazing that publishing is accountable to people besides funders and people with money. We’re living it now. I was at Barnes & Noble today and the table display about what teens are reading was almost entirely writers of color, queer romances, fantasy, books about police brutality. That’s what we fought for. It doesn’t mean we are done or that it’s over—clearly white supremacy never sleeps and neither does patriarchy. We’ve made this amazing surge forward and there’s so much more to go, but I for one, am enjoying this process and this moment for the most part. It’s complicated, for sure, but now we have a voice and we’re able to talk and have difficult conversations publicly. Mostly we have to listen to each other. There are certainly white writers who are writing books with characters of color that are beloved and it’s because they take the time to listen and to get it right. They’re not just creating throwaway characters or painting a white face brown.

And sometimes too, now people sometimes say to me as a POC poet that I get published or things are happening because I’m a POC. And now more books are by POC and awards are going to POC and that we’ve swung too far, but I always say it’s because there’s such a backlog of talent.

When you force writers into a siege where there’s only one spot for us to fill, we can’t afford the luxury of being mediocre. So, we’re going to write bomb-ass books over and over and that’s why there’s the beginning of equality. You’re seeing these lists and awards are mostly people of color because we write bomb-ass books because we had to in order to get published at all.

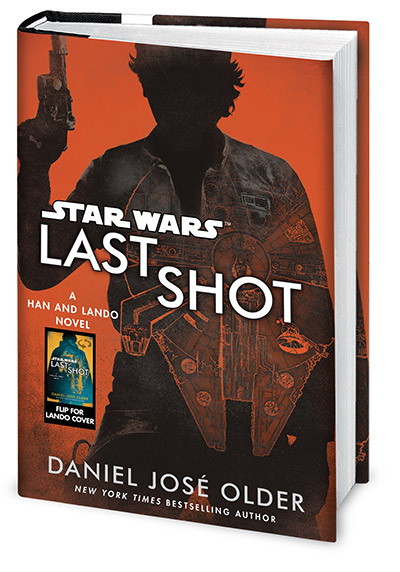

You are working on so many neat projects right now—Last Shot (Star Wars): A Han and Lando Novel. This one is on the New York Times Best Seller list and it’s your second time on the list with Shadowshaper being the first time. Tell me about the Star Wars project and how that got started.

This started from a short story that was in an anthology called From a Certain Point of View that was published last year where writers were asked to write short stories that reimagined Star Wars through the eyes of a supporting character. They followed up, asking me to write a whole novel, which was a dream come true because I’ve always been a Star Wars fan.

Did it require you writing in a different style?

The challenge was to play in someone else’s world but to maintain my own voice, and also to capture the voices of Han and Lando. You don’t want to do the same thing over and over but you don’t want to make them feel completely not of that place. I grew up on Star Wars so it wasn’t much of a stretch because that’s one of the ways I learned how to tell stories. It was a lot of fun.

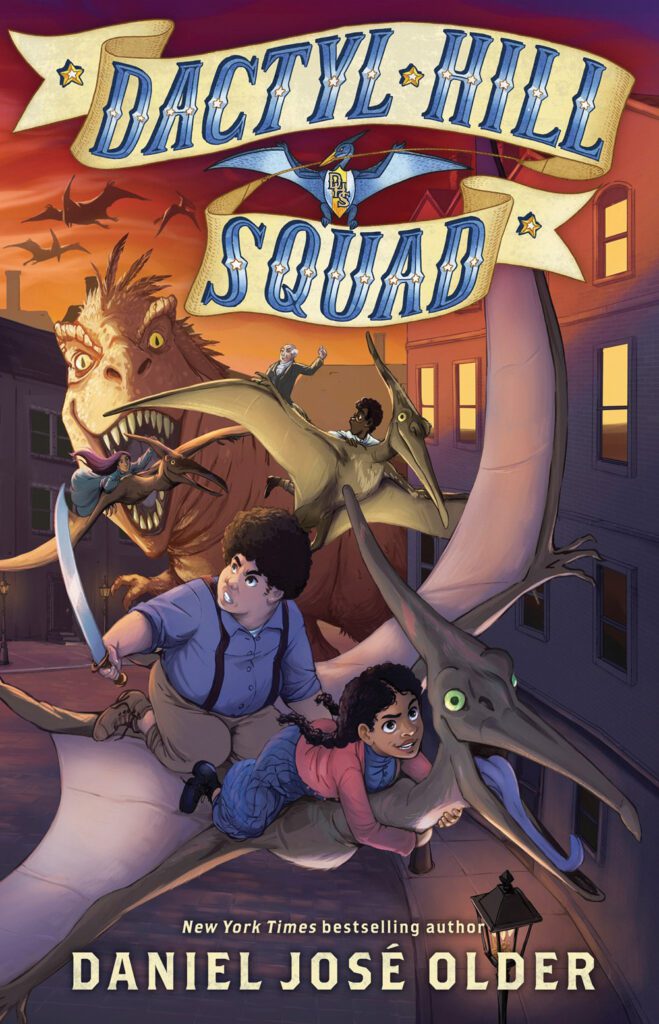

You’re also working on Dactyl Hill Squad, which is a middle grade series. What’s your writing process like? Do you work on lots of projects at once? What’s your day look like?

Right now, I’m working on Dactyl Hill Squad and it’s at least a trilogy and it’s about kids of color in 1863 in New York City during the Civil War, but it’s a world where dinosaurs walk alongside us. It was really fun—that first book is the most fun I’ve ever had writing. I became a huge Civil War nerd. There’s so much about New York City at that time that I didn’t know about. I just finished the sequel and I’m in the middle of edits on that. Basically, I wake up, have breakfast and start writing. That’s the flow right now. I try to have 1,000 words a day before lunch and maybe the same after.

Do you plot out a narrative?

Oh, I hate that. It makes it much more enjoyable for me to find out what’s going to happen.

How did dinosaurs come about? Did you write into it or did you have that idea first?

I wrote a comic book script that took place in old-time New York with science elements and at one point, there are dinosaurs and that small detail captured my imagination. And then someone said that I should do a middle grade fantasy and I had everything I needed to start. Once I get invested in a project, it’s really exciting.

Your protagonists are all POC, right?

Yes. Except for Han Solo.

38 is kind of getting to that reflective age—you’re not the new kid on the block anymore, but you’re not very old either. What advice would you give to younger writers or the younger version of yourself?

Stick to your guns and have a story you want to tell. Sometimes we cut off stories on the presumption that it won’t stay intact through the gauntlet of the publishing industry. And that’s not as much of the case as we assume. This is not to say the industry isn’t messed up. I didn’t expect to be able to publish Shadowshaper with all its critiques of white supremacy, gentrification, and cultural appropriation. I thought at some point, they would try to make me cut it or they wouldn’t publish it. And that didn’t happen. I’m not saying I would have changed anything. That’s the book I edited more intensely and thoroughly than any book I’ve ever written because I was literally learning how to write in the novel form with that book. But none of the changes struck at the heart of what I was trying to do which was to tell this great adventure story that also dealt with the reality of being people of color in America’s white supremacy and patriarchal world. If I had thought there was no way this would have been published and had written a half-ass version of this, it never would have been the book that it is. So much of being a writer is determining which hills to plant flags on and to fight for. That’s not something you get a Master Class in anywhere. Take time to determine what success means to you so that before you get there, you recognize it.

Also, the idea of finding someone good to work with and sticking with them. Ultimately, it’s about building community with other writers—making sure you have people who will have your back but will also keep you accountable.

You had said once that reading the works of authors such as of Octavia Butler gave you permission to “be found in” books too or gave you permission to write. Do you view yourself as a role model and what kind of feedback do you get from your readers?

It’s been one of the best things about being a writer—being inspired and inspiring other people. It was so nice to be inspired by books by Tananarive Due, Jacqueline Woodson, and others and then realizing Shadowshaper really changed the game for younger writers who are coming up today who tell me that Shadowshaper could be that light for someone in the same way other books were lights for me.

How do you give back to the community or want to?

I stopped teaching this year professionally because I needed the time to write. It allowed me to write more, but it also allowed me to teach in more intentional ways. I actually love teaching, but I don’t love it when I have to rely on it. I just love relying on writing because it’s what I’m meant to do on this planet. I’ve been working with kids more. I talk to kids a lot about valuing your own work and your voices matter and to stay true to them. And I like telling them what the publishing world is really like. I don’t think writers should be walking around with an inferiority complex.

What’s next for you, or what do you want to do when you grow up?

Moving forward, I want to start working on scripts. Two of my series have been optioned—Bone Street Rumba and Shadowshapers—so that’s very exciting.