In 2017, Dawn Murray, a Professor in the Environmental Studies Department and Director of the BS in Environmental Studies, Sustainability, and Sciences, traveled to the Kingdom of Bhutan by invitation from the Monpa people to collaborate with them to document the knowledge of their last community healer, Ap Tawla. Ap Tawla, who was in his 80s, feared that his death would mark the extinction of much of the Monpa people’s collective wisdom, which like a braid reaching back in time, connects them with their ancestors.

Looming boulders, marbled in hues of black and embroidered in moss, are scattered throughout one of the richest temperate rainforests in the Himalayas, the Black Mountains located in the southwest region of Bhutan. These mountains, with their moist and humid forests, are difficult to access, though that is slowly changing. They are home to Monpa land and the Monpa people, descendants of people who inhabited the region’s mountainous caves during the last Ice Age, and who have tended this land and the knowledge it offers for thousands of years.

On Murray’s first trip to Monpa land, she had a surprising experience when—after a flight, then a bus ride, then a long trek—they stopped at one of these monolithic black boulders that was not quite at the village’s entrance. Before going any further, the guide asked her to rest her hands on the rock’s cold, slick surface and feel its energy, explaining that these rocks and the surrounding mountains were the domains of gods. “I’m a field biologist and healthily skeptical,” Murray says, so she didn’t know how to fully make sense of what she felt. As she explains, “I definitely felt energy coming from that first rock, and I thought, what’s happening? Am I making this up? I don’t know. I definitely feel energy here.”

Murray has found ways to hold space for beliefs that might initially seem to be at odds with the tenets and processes of Western science, which tends to be grounded in rigid, hierarchical categories and is not always synonymous with conservation. Nature as an object of study is very different from being in relation with nature in ways that are regenerative to the balance of ecosystems.

The Monpa people participate in protecting that balance by viewing nature through an animist framework, meaning their deep respect and care for nature is rooted in life. This also means that places like their local mountain range are believed to be alive, which is why they have a cultural prohibition on summiting them—instead, they honor them from afar. Learning this, Murray couldn’t help but contrast it with the culture of mountaineering in the U.S., where summiting peaks is as much of a custom as the Monpa people’s custom of revering them in song.

This is just one of many differences between Monpa and American culture—and with difference comes the danger of one culture, the more fragile one, getting erased in some ways. This is an ongoing concern of the Monpa people. As the Kingdom of Bhutan has modernized, they have built clinics and schools in Monpa villages, which raise well-founded concerns amongst community members that without proactive conservation efforts, modernization will be coterminous with the loss of cultural cornerstones. And a major concern has been the loss of knowledge of plant medicine. On a very local level, this concern increased as no one from younger generations stepped forward to apprentice with Ap Tawla. As Murray puts it, the Monpa people are not opposed to modernization, they just want to ensure that their language, culture, and collective knowledge are not lost to assimilation.

Working Alongside People

Murray’s background is in marine biology and intertidal ecology, but she has over a decade of experience working at the confluence of science and culture. This has given breadth and complexity to how she thinks about science and what being a scientist entails in the age of the Anthropocene. Due to humanity’s ever-expanding impact on the world, any science that lends itself to conservation efforts has to consider the human element.

Murray decided long ago that as much as science involved humans, then she wanted to work alongside people at a grassroots level. This often means working to support the people already protecting the environment. In Murray’s case, that has involved collaborating with different Indigenous communities worldwide.

When Murray is on Monpa land and with Ap Tawla, she sees herself not as a researcher, documentarian, or scientist but as a guest. She strives to collaborate in stewarding knowledge and ways of being. “I don’t want us to forget,” she says, “that there are people like that in the world who walk with nature, connected with nature, not separate from nature.”

But Murray is also an academic, and within the field of academia, there is pressure to publish one’s “findings.” To Murray, though, there is something inherently problematic nestled in the word “finding.” It suggests that either something was lost and now found or something previously unknown has been discovered. But these knowledges are not lost or undiscovered; they have existed within the culture of the Monpa people since time immemorial. It is simply that this is the moment when they have been shared with Murray—and through her, with the wider world.

Another ethical question Murray grapples with is how to share this knowledge without exploiting the trust of the people who shared it with her. Is an academic paper a capacious enough form to share this knowledge without replicating the historical violence of studying people as objects and assimilating their knowledge into Western frameworks? What does it mean for these stories to be peer-reviewed by people who might not have any connection to the Monpa people? How does one reconcile working against extraction by practicing being a guest while also operating within institutions often built on processes of extraction?

Yet these are the questions Murray wants to be grappling with because, as she puts it, “We’re all connected. We’re completely connected. And I think we can forget that. These people who walk in the world in a different way are gifts to all of us to remember that connection to nature and each other is part of who we are.” It’s that sense of belonging, that connection to place, and the community that emerges from those bonds that reminds Murray that part of the work she does as a scientist and educator is to learn and share ways of finding a sense of belonging that is intimately connected to and with place.

Ap Tawla’s Legacy

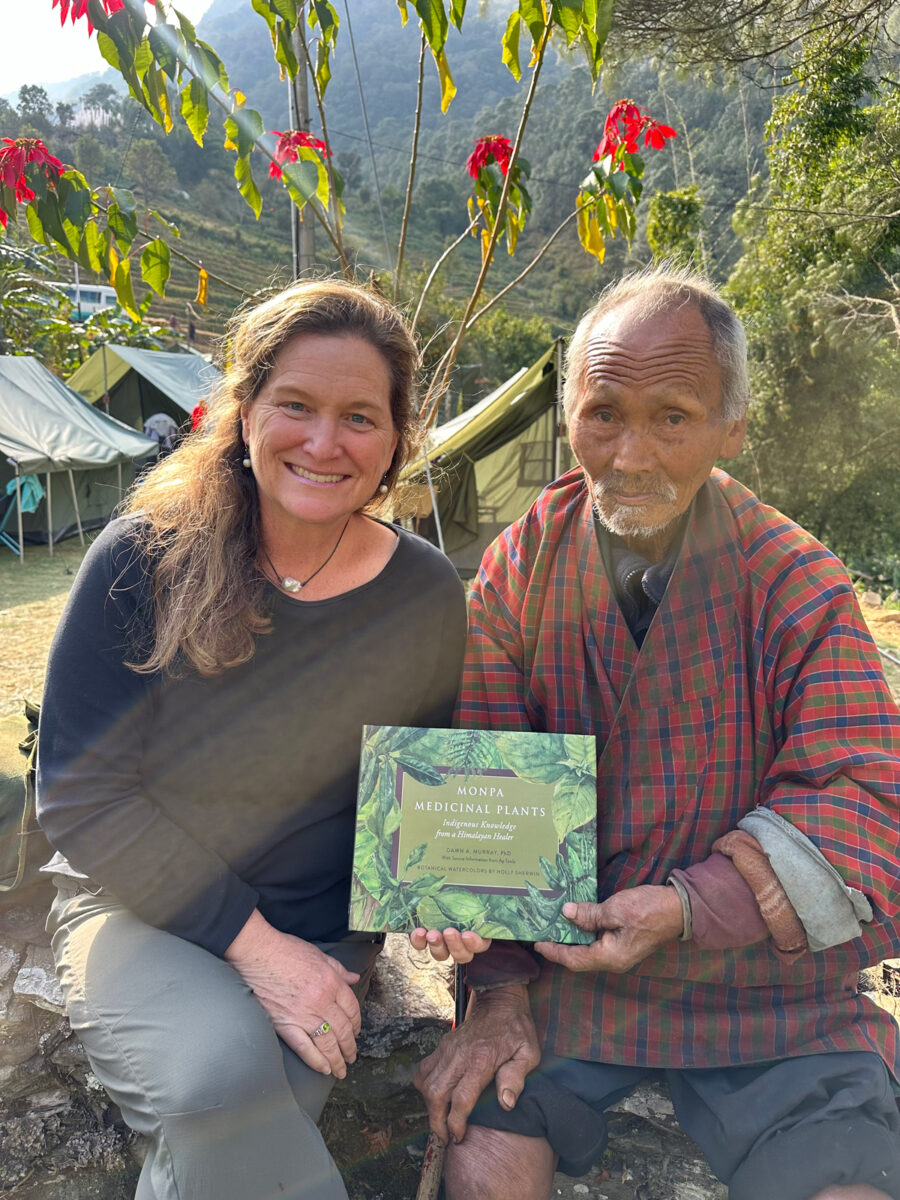

The connection between Murray and Ap Tawla has only grown stronger over her many return trips. On her first visit after the hiatus caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, Ap Tawla joined foreheads with Murray and thanked her for coming back. This was in December 2023, when Murray returned to Bhutan to deliver Monpa Medicinal Plants: Indigenous Knowledge From a Himalayan Healer, a book that caps off six years of working alongside Ap Tawla. It describes thirteen different medicinal plants both and contains botanical illustrations of each. For three days, Ap Tawla’s niece ran around the village, book in hand, boasting about her uncle’s knowledge and espousing her desire to be just like him.

This was a sign of a more profound change unfolding within the community. Murray said that her and her colleagues’ presence and work with Ap Tawla caused a positive disturbance in the status quo. Their identity as people who came from elsewhere made them inherently interesting, together with their work with Ap Tawala led to a shift in perspectives in the local community. This continued as they compiled the book and recorded Ap Tawla’s knowledge in a series of interviews now kept in the archives of the Kingdom of Bhutan. Eventually, these changes led younger people in the community to take an interest in learning from him.

There was no way that a book was ever going to document the breadth of Ap Tawla’s knowledge, especially when so much of the knowledge is connected to and transmitted through the land. And as it turned out, the successful preservation of the Monpa people’s cultural knowledge of medicinal plants didn’t hinge entirely on a Western person recording the knowledge in writing. “The true success,” Murray explains, “is that Ap Tawla has two apprentices.” Murray believes that Ap Tawla knew this might happen all along—and that the emergence of these apprentices was possibly encouraged by the fact of Westerners showing him so much respect. She sees his brilliance as a medicine man embodied not just in his work with medicinal plants and broken bones but also in his thoughtful interventions on the psychological patterns within his community.

And other perspectives shifted, too. The first few times Murray traveled to Monpa land, her guides and interpreters, who came from the capital, approached the journey to Monpa land with reluctance, realizing Monpa land is distant and disconnected from urban life. Now, however, they eagerly anticipate the trip. Upon arrival, if Ap Tawla is not occupied with tending to a cow’s sprained ankle or ameliorating someone’s migraine, these guides and interpreters seek out his healing knowledge. They ask for his help with ailments afflicting themselves and their families.

But it’s not just his expertise they look forward to—it’s all of the food that comes from this land stewarded by their Monpa hosts. “The guides fight over who gets the tangerines from Monpa land, because they are absurdly fresh,” says Murray. And they also all want the bananas, she explains, “because they taste out of this world, unlike any banana I’ve ever had before.”