A popular proverb says, “When sleeping women wake, mountains move.” That is, when a woman becomes aware of the inner power she holds and begins to tap into that well of strength and resilience, the results are magical and literally world-changing. This, at least, is true of Cara Mia Villalobos—an Indigenous activist and artist from the Pacific Northwest.

A full-time undergraduate student at Antioch University Seattle, Villalobos is working diligently towards her imminent graduation in the fall of 2021. In the meantime, she is also working to change the hearts and minds of ordinary people around the issues of justice and sovereignty that are most important to her. She is using her voice as an instrument to build bridges between people and institutions

But for a long time, Villalobos struggled to find her voice. The path to gaining her full power involved grappling with her cultural identity and struggling through the loss of a career. Despite it all, Villalobos prevailed. This piece is a song to Cara Mia, detailing the voyage of her awakening in five movements.

1. Born with Purpose

Villalobos belongs to the St’át’imc Nation, an Indigenous people whose lands are located in the southern Coast Mountains and Fraser Canyon region of what today is the Canadian province of British Columbia. Her band and family lineage are the P’egp’ig’lha people or Frog clan. They are known as water protectors.

But these roots were not always as clear to her as they are today. Says Villalobos, “By design of colonialism, intergenerational trauma, living off reservation, and my mother attending a residential school near Hope, B.C., I don’t know a great deal about my culture.” Her mother was raised off reservation, in Seattle, and in Villalobos’s childhood she visited family and spent time both on and off reservation. Both ways of life had their own set of challenges and benefits. “The first challenge when living off reservation is recognizing your collective self in anyone else that surrounds you,” she explains. “To find collectivity is to find family. The second challenge is the constant tug-of-war for a sense of worth and over human commodification.”

She now describes these years of her childhood as being “a deep sleep, disconnected from Self, which was like experiencing a cultural void.” She goes on to explain, “There was no true self, only the self I was hurriedly constructing in response to every heartbreak, to survive the nearly constant and always unnatural feeling of being othered.”

Adding another layer to Villalobos’ intricate cultural identity was having a non-biological father who was Black, who had raised her from infancy and for whom she was “Daddy’s Girl.” Being a diverse family in what was still a widely segregated city during Villalobos’ upbringing exposed them to open racism and racist social interactions.

Villalobos remembers a specific time when a white family refused to enter a store as Villalobos, her mother, and aunt were walking out. “They made a point to get in our way, just enough,” she explains. “And the man said—directly to us—and indirectly to his wife and young child, ‘Let’s go. We don’t want to touch anything those dirty Indians have touched’ and they turned and left.” It was a terrible experience, but she also couldn’t help seeing some irony in it. As she says, “And that was at a thrift store!”

This experience, among others, caused 10-year-old Villalobos to retreat inward and to begin separating herself from anything that caused her social pain. “It was the first time I had heard the words dirty and Indian used together,” she explains. “I’d sure gotten the message through social cues such as games of cowboys and Indians and popular media, but this was the first real spoken aloud judgment to personally strike me.”

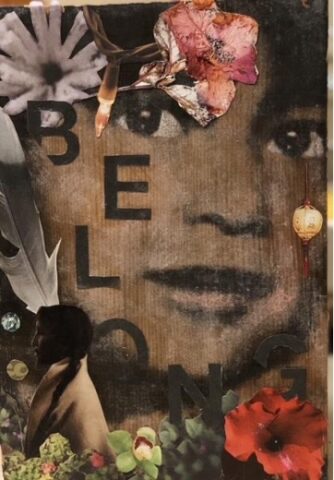

These words became the start of a long mental list of things that she vowed not to allow herself to be. As she says, “Along with shame, I developed a sense of not belonging to anyone or anything. My path of trying to belong led to my own spiritual and emotional disappearing act, which I feared would make me vanish entirely.” Trying to fit into a normative standard that ultimately had no welcoming room for her was a soul-crushing struggle and source of constant confusion and anxiety.

“I started out to be a pretty bright, sweet, and highly socially-sensitive kid,” says Villalobos. “Little by little I devolved into an uneasy, never-satisfied, shame-drenched, insecure, defensive, fearful woman. And all of that began with that little girl in front of the thrift store who was told that she was a dirty Indian. This was my period of a slow and agonizing spiritual and emotional death.”

2. Dormancy and Struggle

All of these forces conspired to make Villalobos hide her passions and personality. This was hard because when she was a little younger she had been active in supporting what was right. She had supported Greenpeace, selling things at fundraisers, and generally being an activist. She had found refuge and passion in her love for reading stories and especially stories of justice. And while she was in elementary school she even gathered with friends to start a successful campaign to rename her elementary school after Martin Luther King, Jr. As part of that renaming, Coretta Scott King (Antioch College BA ‘51) came to listen to her and her classmates speak at the school dedication, and Villalobos was able to share a few private moments with her.

But this early lesson in how using your voice can lead to important change became subsumed by trying to survive in a racist and colonized society. By middle school, Villalobos had organized her life to fly under the radar. She felt safest there.

Remembering this, Villalobos says she felt “robbed of my innocence and ability to self-actualize by living in a colonized society.” She was stuck in a cloud of want and lack.

The key to healing would be found, eventually, in reconnection to her family, culture, and the natural whole. But before she came to that realization, she had to go through a period of fabricating false histories to avoid questions about her identity.

Villalobos first began passing as Mexican when she was inevitably asked, “What are you?” She would answer to match her last name, which she got from her biological father. But quickly she noticed by reading people’s faces and reactions that identifying as Mexican did not mean she would be less denigrated than if she said she was Indian. Despite these efforts, her classmates still did not accept her. So she changed again. She began to identify as Spanish, instead, which she thought would be more favorable to Anglo ears. She was living a lie, though: not one drop of Spanish blood could be found in her lineage.

“I wish I could go back and hug the girl—and then woman—that I was during this long period of my life, and maybe encourage her to try a different way”, Villalobos says. She would have been better off looking for a way that would allow her to merge her two cultures and embrace her uniqueness.

3. The Awakening: A Call to Fight for Change

Villalobos struggled in high school, where the teaching methods did not match with her learning style, and she missed graduation by a few credits. So she obtained her GED and began working full-time to help support her mother and have a little cash. She eventually found a fairly well-paying job with benefits and career growth potential. So she dedicated herself to it, even though on some level she knew that it was not supporting what she calls her “heart’s true locked-away desire to champion for truth.”

Looking back, she sees this as a necessary part of her journey. But she still wonders if she made the right decision in choosing safety and income over what enlivened her. She describes this period as a time in which. “I shut myself down and instead of pursuing my perfect life, began pursuing the ‘ideal life,’” Villalobos explains. “At least, it was a representation of the life I thought I was supposed to have.”

She landed a corporate position in the travel industry. And for the next twenty-three years she dedicated her life to serving in various roles at the same company. Villalobos survived in the business through three downsizes and countless staffing changes.

Meanwhile, life became standardized and increasingly robotic. She punched a clock and did her job, but she could never ignore the feelings of confinement that came from being part of the only small percentage of people of color at this company. Villalobos says, “I felt … as if I had no voice. I was impelled to remain quiet for self-protection.” It was a good strategy: she received nine promotions over her years at the company.

After over a decade at the company, the internal rumblings of ethical dissatisfaction and frustration with a damaging work environment groaned louder and louder. Eventually Villalobos had no choice but to start calling out the wrong she had experienced, witnessed, and to some degree, played a part in.

“The day-to-day toxicity and power games I was forced to play in order to simply get my work done sucked the life out of me,” she says. “I can’t even claim that I was courageous in ultimately speaking up. I spoke up out of pain and out of a primal need to reconnect to my own integrity, which was impossible in the working environment as it was.”

But rather than being fired, she found herself supported by top management, and became an active leader and reformer within the company. She became active in breaking down intercompany department silos, innovating solutions through collaboration, and became a bridge between staff and management when people did not feel safe to speak their truth to standard authorities.

The experience made her reflect on her life. “I witnessed that I could change the hearts and minds of people with my willingness to discuss hard topics, by standing in greatest-good truth, being fully present and vulnerable, and by always acting from love” Villalobos remembers thinking. “There’s something about seeing the light of humanity in a person’s eyes unwittingly flicker, or watching a person’s hard edges start to soften, which speaks to me deeply.” She started to understand people differently.

The company structure and power dynamic began to evolve. More women received leadership roles and people of color were finally granted top leadership positions for the first time in the company’s long history. Even non-executive staff—the most negatively-impacted group—began to benefit with access to the company’s new commitment to a leadership training program and its greater focus on leader accountability.

Then, in 2015, the company downsized again. This time, Villalobos walked away from corporate life and what she describes as “the tarnished glamour of the travel industry.” Villalobos was back to square one. She once more had to figure out how to move forward.

4. Self-Actualization: Antioch Seattle

Villalobos had always wanted to pursue higher education, and now she had the perfect opportunity to progress beyond her GED. Although her earlier academic years in traditional classes had been plagued by difficulty, she had since been diagnosed with ADHD and had developed research skills through pursuing her own private leadership journey during her career. She knew that she needed to find a school that was flexible and supportive of her goals and time, as she was also caring for her mother. Even with all of her accomplishments in the corporate space, she feared that she lacked the power to succeed in higher education.

“I had no confidence. I had held my head down until I was 42 years old,” she explains. And even when she began speaking out, she says she “rarely received the best reception for using it for good in the corporate world. I left my career feeling battered.”

In her search for what came next, she found out about Antioch University Seattle. She’s now in her penultimate quarter of earning a Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Studies with three concentrations: Leadership & Sustainable Business, Global and Social Justice Studies, and Communications & Media. Having once thought she was a horrible student and that her dream of attending college would only ever be a dream, she now fills her days with coursework, study, research, and finding new learning and experiential opportunities to develop her gifts and skills.

Outside of her concentrations, Villalobos has immersed herself in classes on Kingian nonviolence study. Although she is unsure about the role of community training on her immediate path, she was drawn to complete Level 1 Kingian nonviolence certification training as a community trainer and has recently completed 365 Nonviolence Training at the King Center in Atlanta, Georgia. This proved to be a full-circle moment for Villalobos after her first encounter with Coretta Scott King back in elementary school. She sees her work today as an outgrowth of the immense power of that encounter. “I got to talk with her,” Villalobos says, “and her energy filled me for a lifetime.”

The coursework at Antioch has lit a fire in Villalobos to pursue social justice in some manner. “I rediscovered accountability,” she says. “I felt responsible for what I heard in lectures and became informed and empowered to act.” The environmental courses and the content she ingested took her back to her roots and heritage as being a water protector. She had to champion for her people.

“When my mom died in 2018,” Villalobos explains, “I had the strong desire to return home for the first time in roughly twenty-five years, and when I did, I was joyfully welcomed. Since then, I have been trying to catch up with learning about my land, people, and ancestors, as well as about Indigenous wisdom, history, and issues which impact Indigenous communities.” Through this relearning she has become an environmental activist, and she has spoken at events around British Columbia.

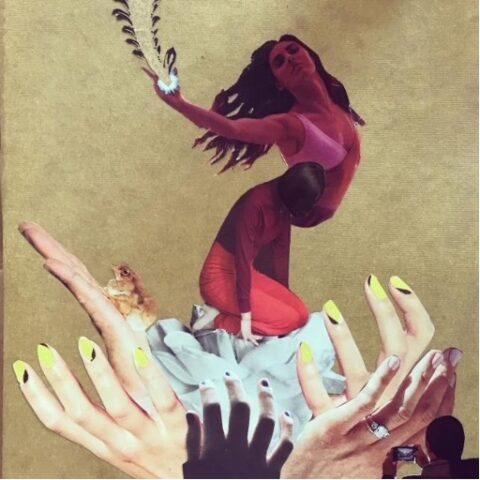

And she’s embracing her creativity and power through art, too. After taking art classes at Antioch, Villalobos is finally obeying her heart’s desire to create. She allows her voice to shine through in her paintings, collage, and in other more sculptural objects (which she refers to as “objets d’soul”) which proudly evoke her culture and heart.

5. Moving Mountains: Changing the World

Antioch has been a rich environment that has helped Villalobos flourish. Studying here has taught her how to put her skills into use and be of service. She says, “I am realizing which weapons in my sacred arsenal are strongest—nonviolent communication, writing, storytelling, public speaking, coaching, strategizing, creativity, resilience, vision, vulnerability, truth-telling—as well as discerning which business, team leadership, and personal development skills I bring to the table.”

She has found her voice and has spoken through both her artistry and in her role championing social justice. In May 2019, Villalobos spoke and participated on behalf of ThePeople.Org, an organization that works to address issues and find commonalities in what affects everyday Americans.

Across the border in Canada, she has relished her renewed connection with her indigenousness and her people, speaking out against the Site C Dam project which is being built along the Peace River in British Columbia. She is particularly concerned about how the completion of this project would lead to harm to area ecology, ruining farmland, violating held treaties, and imperiling the safety and sustainability of Indigenous bands, and preventing the restoration of the Yellowstone to Yukon migration and wildlife corridor. (Read a recent environmental report on this project here.) This year, Villalobos also became an Elder in her Indigenous community, and she is planning to begin an intensive Stl’atl’imx language BA study program towards language fluency this coming fall.

With newfound confidence, she has recaptured her inner power and is, once again, filled with purpose. She stands in her truth now, because it’s hers to speak and because it is required for service to the greatest good. Speaking the truth and championing for others is her joy and passion. Each time she speaks, a layer of shame unfurls itself, from her, her ancestors, and by law of interconnection, from us all, revealing a powerful woman who has devoted her life to creating love and being of service.

“Wherever we are—our homes, at work, simply walking amongst one another—we belong to one another,” she says. “We’re interconnected. That is not an opinion, it is a fact which predates any of us.”

She is committed to doing the work that helps people, organizations, and institutions to recognize and honor that interconnection. As she sees it, only by doing this can we harness our interconnectedness for the “mutual evolution” to transform ourselves, our communities, our environmental practices, and our human-made-and-run institutions. As she explains it, “My path somehow revolves around changing the hearts and minds of people, tapping into ancient wisdom to help heal societal wounds and division, and helping to restitch the tattered remains of the natural world before it is too late.”

Now that the shame is gone, Villalobos has accepted her role as a conduit where truth and knowledge can flow and help us all to decolonize. By choosing to speak, her voice empowers others, thundering back to her ancestors. Her voice is healing their shame. Her truth is healing their shame. And it’s pointing the way to a better world for everyone.

“It’s time for an Age of Humanity,” she says. “Going into this era I want every one of us—the willing and resistant—to recognize the light and power that exists within us all, singularly, which becomes amplified by our connectivity, and which just waits for us to tap into it for our collective good, planetary survival, and our evolution.

To learn more about the undergraduate programs at Antioch Seattle follow this link.

To