As a third grader, Marc Stallion stood in his closet, the one place he knew he could find privacy. There, by the coats, where it was calm and quiet, he pulled paper napkin after paper napkin out of his pockets. Earlier in the day, he had taken these from the lunch line at school; before, amidst, and after class, he would fill them with his own poems. Back at home, in the intimacy of his closet, he recited them over and over again. He listened to the way his voice brought words to life, the ways words gave him a voice.

“If it weren’t for poetry, I wouldn’t speak,” explains Stallion, a 2020 graduate of the Antioch MFA in Creative Writing. “I literally had nobody to listen to me, and I needed to be able to listen to myself. I would recite the poem five, six times, and every single time, I would get this feeling of gratification for myself.” Over the decade and a half since he stood in that closet, he’s taken this passion for expressing himself and turned it into a career that is polyphonic—writing poetry, studying martial arts, acting for the stage and the camera, filmmaking, and running a nonprofit, give breadth to how he finds expression.

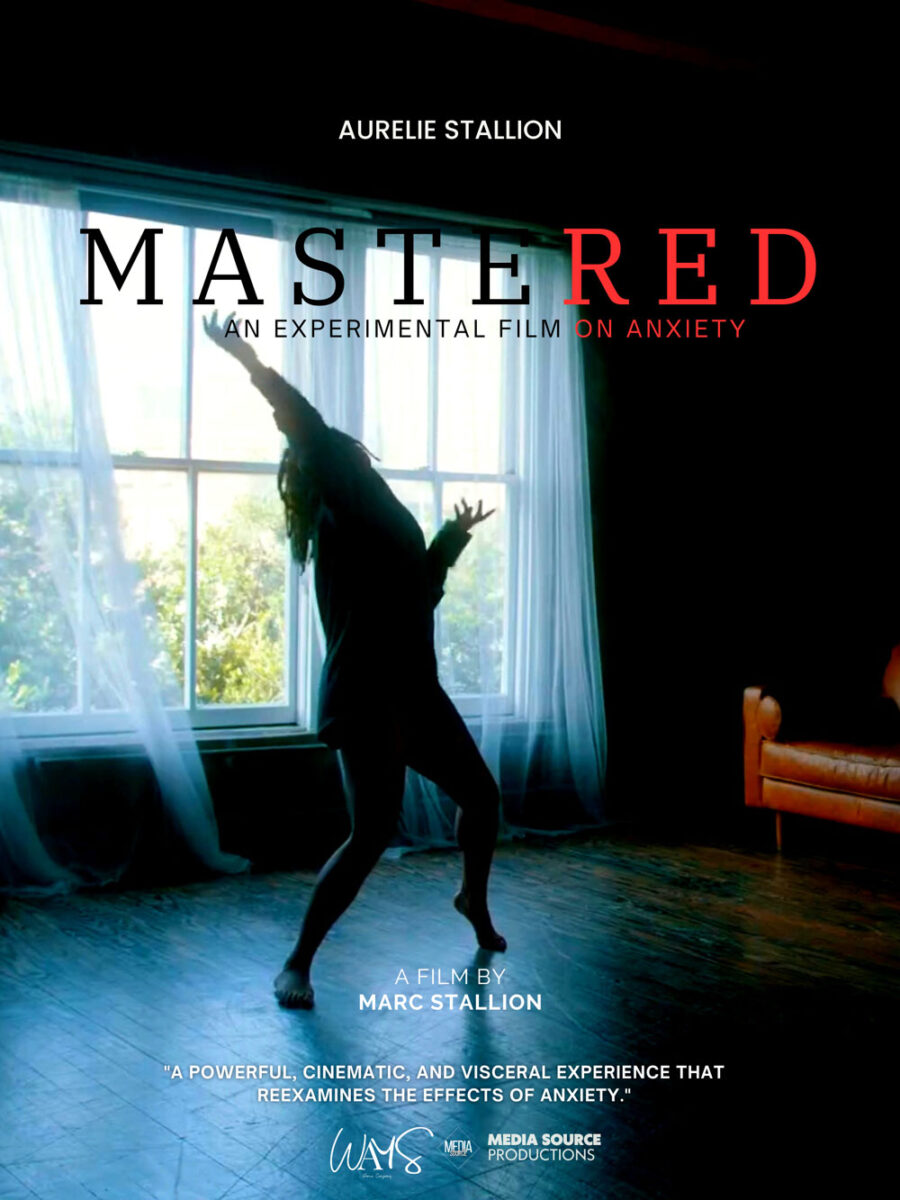

Now, in 2023, Stallion is promoting his latest project: a short film about anxiety that stars his partner, the dancer Aurelie Stallion. The film is titled Mastered, and it takes as its central metaphor the idea that you can feel enslaved by anxiety, overcome by involuntary thinking and behaviors. With the film, which he is currently showing at festivals and on college campuses, Stallion aims to challenge stigmas and inspire conversations around mental health.

“I use everything for everything,” Stallion says, meaning where some people see boundaries, Stallion sees ways to create overlap and build his skills and interests, disparate as they might seem at first. Poetry taught Stallion how to tell stories, acting taught Stallion how to embody his stories, and filmmaking taught Stallion how art could be a tool for healing. Everything can be used for everything.

A Partnership of Dance and Poetry

One of the cornerstones to making Mastered is Stallions’ relationship with his wife, Aurelie. Stallion and Aurelie first began collaborating as undergrads at the American Music & Dramatic Academy, Los Angeles. They were collaborating on performances that brought his spoken word poetry and her dance together on the same stage—they thought of these performances as physical narrations of poetry and verbal expressions of movement. “I was like, we should tell the story on two different levels, in two different ways, at the same time,” Stallion says.

In April of 2023, Stallion was conversing with a client who expressed feeling enslaved to his anxiety, explaining how there were moments when he was overcome by involuntary thinking and behaviors. This conversation seeded a desire in Stallion to use his art to address issues that underpin much of modern experience—like living and coping with anxiety—so Stallion began to consider the best way to tell the story of anxiety.

Given that anxiety is an emotion that manifests in physical ways, Stallion asked Aurelie, who is also a movement coach, to collaborate with him to depict anxiety through embodiment. Inspired by the collaboration inherent to filmmaking and the capacity of the medium to tell a story on many layers—from lighting to sound design to editing—Stallion decided to approach this complex emotion through filmmaking.

Stallion describes Mastered as an experimental film — rather than drawing on traditional forms of narration or clinical explanations of anxiety, Aurelie interprets anxiety through movement and gesture. At the same time, Stallion uses metaphor and personification to create an accompanying voice-over narration that evokes the emotion of anxiety rather than rendering anxiety through representation. One of the worlds that Stallion comes out of is that of slam poetry, and this film contains the same energy of intense emotions expressed through thoughtful storytelling.

Stallion and Aurelie hope this experimental portrait of anxiety, one of three short films, will foster discursive spaces where people can reflect on anxiety in positive ways that work toward healing. “Art and wellness have to work together,” Stallion says, and this sentiment aligns with their desire for these films to be didactic tools used on college and university campuses to help de-stigmatize conversations around mental health.

During the initial screening and discussion at Harford University’s Theatre Program in Connecticut, Stallion was amazed at how students opened up. They shared how witnessing anxiety and guilt portrayed through movement made them reconsider how their own artistic practices and mediums could engage emotions and conversations about mental health in innovative ways. “Art allows the freedom to offer more perspectives on mental illness and mental health awareness. It’s just very liberating to be able to see and feel some of the deeper issues that we all suffer from. We want people to see themselves and feel like, ‘This is normal. I can speak about it. I can use film, poetry, and dance as tools to help individuals heal or begin their journey into wellness,” Stallion remarks.

Finding Grounding Through Martial Arts

Stallion’s own journey towards wellness has been a dynamic one, deeply shaped by how he has come to understand movement. Movement—be it of words on the page or the body through space—is the ligature that connects his artistic practice to his long-standing practice of martial arts.

Stallion didn’t first encounter Muhammad Ali through boxing. He heard him on the radio when he was seven years old. Ali was in the middle of an interview when he broke into freestyle poetry— Stallion can still recite those verses word for word. Ali’s playfulness, rhythm, and elegance left an indelible mark on Stallion, who thought, “I want to speak like that. Then I saw him train, and then I saw him boxing, and then I just fell in love with Muhammad Ali and his way of thinking and sense of service. We haven’t had another athlete with his sense of service.”

Muhammad Ali introduced Stallion to a concept of movement characterized by swiftness, fluidity, and non-aggression. In high school, Stallion transitioned from Western boxing to capoeira to enhance his foot skills. Then he found Tai Chi. Stallion says, “Tai Chi transformed everything. It changed the way I thought and how I responded to people. Tai Chi is not aggression, it’s not striking, it’s not even defense. It’s countering. Everything is countering and finding balance.” Stallion began to notice changes in his beliefs and attitudes; rather than fighting systems that weren’t working for him, like education, Stallion began reclaiming them by telling his own stories in the ways he wanted, often involving cameras and acting.

Stallion had grown accustomed to the camera’s gaze because, as a freshman in high school, he inherited all of his grandfather’s camera equipment. Enamored by how stories unfolded through images, Stallion began making short films that centered his stories, which was novel, given that his poetry always told the stories of others. Never dissuaded by having to fill a role, he began to write, direct, and act for the camera. His talent and enthusiasm for acting led him to the American Music & Dramatic Academy in Los Angeles, where he graduated with a BFA in acting.

During his BFA, Stallion wrote and produced all his plays. Getting these approved each semester was a laborious process, but the labor of the creative process is what Stallion enjoys most. “The labor, the rehearsal, the practice, the production is my favorite part of the creative process because it’s when creative ideas flow and things change. I didn’t care about being famous. I wanted to create. I want to direct. I wanted to write and produce,” Stallion says. And labor often includes convincing people that an idea is worthwhile.

Professors repeatedly told Stallion that his idea of producing a play with a twenty-minute combat sequence was not feasible. Wanting to put the combat-acting skills students were learning to more frequent use and to stage them outside the context of Shakespearean plays, Stallion was persistent in his search for a professor who would agree to supervise the combat-centric play. Eventually, he met Nathan Mitchell, a professor and famous stuntman working on a variety of action-packed movies in Hollywood.

Under Mitchell’s supervision, Stallion produced The Cave. Stallion gave climate disaster and injustice a new aesthetic as ethical dilemmas unfolded through highly choreographed, long combat sequences. Since he produced The Cave, Stallion hasn’t seen another play that centers on combat—they are considered too much of a liability. Nonetheless, he hopes to continue pursuing efforts like these because, as he says, “I was producing my own stuff and doing it how I wanted to, which was different, very different from what was considered the norm at the time. I was drawing inspiration from wanting to provide opportunities. I wanted to give opportunities to students who felt they didn’t belong in any of the productions. Who felt like what they did was too different.”

Reclaiming Education

Growing up with undiagnosed dyslexia in an unstable household and amidst a schooling system that failed him in countless ways, Stallion learned at a young age to follow his interests and self-validate. After completing his BFA and wanting to hone his writing skills, he gravitated towards Antioch University’s low residency MFA. The low residency model meant Stallion could have more autonomy over his education while still being among a community of writers from various backgrounds and experiences, a balance he sought.

Stallion surprised himself when, at the end of his degree, he chose to pursue a Post-MFA Certificate in Teaching Creative Writing at Antioch — he hadn’t imagined building a career for himself in the system that had failed him. But in the process of reclaiming education, he learned that he could change other people’s experience of education. This unexpected interest in teaching led him and Aurelie, who is from Haiti, to co-found I Got Next.

I Got Next is a nonprofit organization that works with schools and orphanages in Haiti to create opportunities for students through artistic expression, social-emotional learning, mentorship programs, and self-discipline rooted in martial arts.

Stallion’s commitment to learning and teaching different mediums of expression stems from his belief that “Each medium has benefits, and they all tell the story differently.” The differences and nuances that proliferate through interpretation complicate how we understand any given topic, and Stallion wants his stories to engage the complexities of being human. In many ways, Stallion’s life experiences and his body of work leading up to this point have equipped him to create ‘Mastered’ and tackle the creative challenges that await.”