Year: 1964. Location: Mississippi. Organization: the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC; pronounced “snick”). Campaign: Freedom Summer. Weeks earlier, three young civil rights organizers went missing. They were among the many Black activists who had been killed over the years. People are afraid. White supremacist hostility is rampant.

On one of the many tense afternoons of that summer, a twenty-year-old SNCC organizer, Judy Richardson ’78 (Baltimore, BA), is in SNCC’s Greenwood, Mississippi office when June Johnson, a 16-year-old local organizer, rushes in. June asks her to drive to the segregated county hospital because Silas McGhee, a young civil rights worker grounded by a strong Black movement family, has been injured during a protest when a white vigilante threw a rock through his car window. Silas had been sitting in the “white section” of the movie theater to test the 1964 Civil Rights Act. He has now been taken to the segregated county hospital with glass in his eye, and needs support and protection.

Richardson has the keys to one of the SNCC vehicles—from the “Sojourner Truth Motor Fleet”—and drives with June to the hospital. Upon arrival, she and Johnson see a mob in the outdoor parking lot, and run quickly to enter the hospital. They find six FBI agents sitting around in the hospital waiting room.

“I see six FBI men, and they’re all milling around. You know: they’ve been called, but then they’re doing nothing—as usual.” This is Richardson, talking via Zoom, sixty years after the events of that summer.

In her telling of the story, shortly after her arrival a rock was thrown through the picture window in the hospital waiting room. And like that, the FBI agents all rushed to hide behind a wall. “I’d never seen FBI agents move so quickly,” she says.

“I’m screaming at them, you know, ‘Why don’t you do something?’ Now, I knew they never did anything. Still, I said, ‘Why don’t you do something?’”

Despite the danger, Richardson peeked around the wall to see where the mob was and then went to use the coin phone on the wall to inform the Justice Department and the SNCC National Office in Atlanta about the emergency situation. She was able to get through to the Atlanta office. After June Johnson confirmed that Silas’ family was there and that he would be okay, she was set to return to the SNCC office. The local sheriff had finally been instructed by federal authorities to escort them to the car in the small outdoor parking lot.

That was the end of the story—at least that’s how Richardson had been ending it in lectures and class visits for years. But then, she explains in our interview, she had a conversation with Johnson about the incident when both were being interviewed by a CBS news affiliate to protest the misinformation in the 1988 film Mississippi Burning. It was there that Johnson shared a slightly different memory of how the standoff ended. In Johnson’s telling, when the sheriff came and begrudgingly said he would escort her to her car, Richardson, instead, insisted on a guarantee of safe passage all the way back to the SNCC office. Eventually, the sheriff acquiesced.

Richardson did not remember this detail herself, and she explains that often traumatic memories are blocked out so that you aren’t made dysfunctional by the danger—so you can keep going. That’s part of why conversations with others and preserving memories and physical materials through archives and documentaries can be so important. No one person can hold the whole memory of a movement.

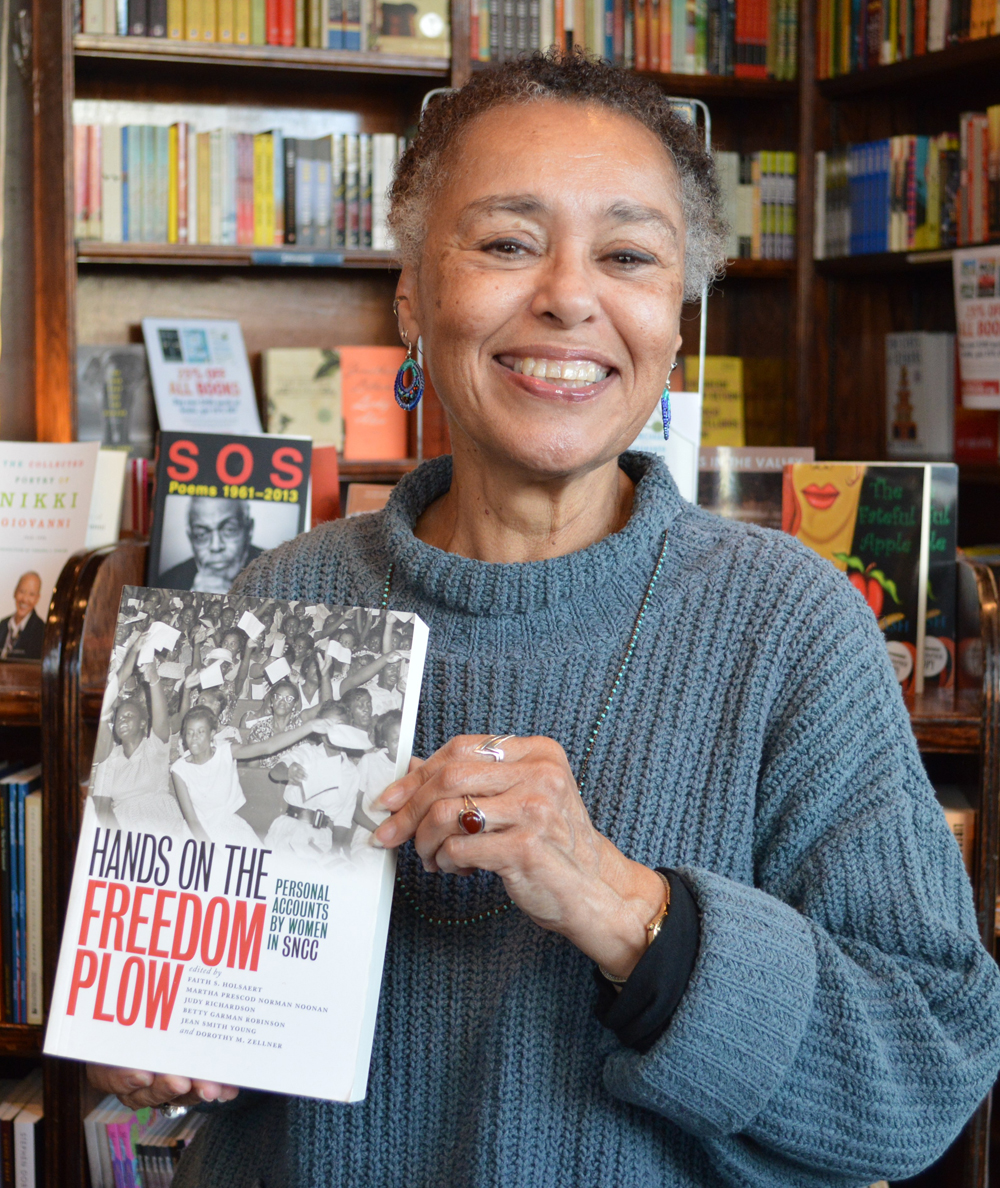

Documenting and preserving the memory of these movements and the people involved has been an essential aspect of Richardson’s work over the last half-century. Her life and work as a documentary filmmaker and civil rights activist are an example of a sustained, constructive, holistic, community-focused approach to grassroots organizing over the long haul. Richardson played a pivotal role in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) during the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, helped found and run the pioneering Drum & Spear Bookstore (the largest African American bookstore in the country at the time), and has spent a long career as a documentary filmmaker and educator. She is one of our nation’s quintessential champions of social justice.

In a recent three-and-a-half hour conversation with Richardson, she shared many stories about this work, how Antioch helped make her work as a professor possible, and her advice for those working towards civil rights and justice today. She cautions young activists not to be discouraged if the change they’re working for doesn’t occur in their lifetimes—though she herself has participated in moments of significant positive change. The main thing is: if you do nothing, nothing changes. She says that the pursuit of social justice often feels like two steps forward, one step back—luckily, she loves to dance.

Richardson has an energy, sharp intelligence, and a particular, grounded yet fierce joy that I associate with empowered matriarchs—women who have earned the trust, respect, and love of their communities. As we talk, I quickly realize that precise communication is important. When I reflect back on something that isn’t accurate, she gently clarifies the point.

I learn a lot over the course of our conversation. Many of the more well-known details I’ve previously read about or learned in American history classes, but now I learn them on a level of human experience that perhaps can only be conveyed via the first-person account of a talented storyteller. I start adding events and people to my mental historical calendar that I will likely not ever forget, because through Richardson’s telling, they are no longer abstract names and dates, they become more personal and thus more relatable—this is the power of first-person narrative, as Richardson well knows.

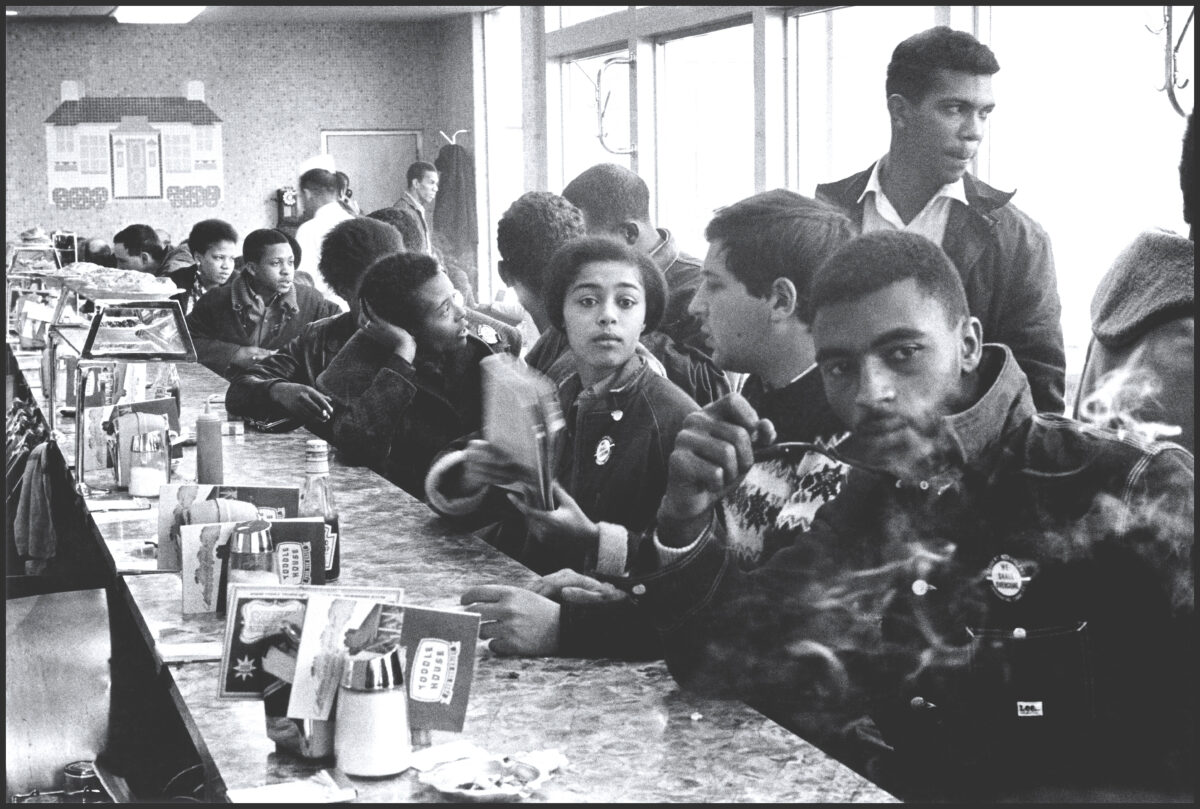

As a college student on a full, four-year scholarship to Swarthmore College in the early ’60s, Richardson didn’t know that she was on the verge of becoming involved with organizing as a lifelong vocation. Freshman year she had a work-study job bussing tables in the college cafeteria, which was where she encountered the Swarthmore chapter of the nationwide, primarily white activist organization Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), which strongly supported the student sit-ins that mushroomed through HBCU’s in 1960.

“There was an all-Black, all-female cafeteria staff at Swarthmore and this SDS chapter was working with them,” Richardson explains. Soon she learned that the chapter, which called itself the Swarthmore Political Action Committee (SPAC), had three prongs of activism: trying to improve the cafeteria workers’ wages and benefits on Swarthmore’s campus; working on a tutorial to improve education in the segregated Black schools in Chester, PA; and supporting a grassroots protest against segregated businesses in Cambridge, MD. Richardson soon decided to travel with SPAC down to Maryland and join one of the protests there.

“I go on a lark,” Richardson recalls. “It’s not because I know anything about SDS. It’s not because I want to join any kind of movement. It’s just ’cause, as I say, my mother’s not there to stop me. And I’m exploring and seeing what’s out there. You know, ‘What’s new?’”

One of the demonstrations she participated in was in front of the Choptank Inn, a bar and grill that refused service to Black people. “I’m standing there near the front of the line,” she says. “I look through the front of the restaurant, and it’s dark. It’s dirty. It smells of rot-gut liquor. And I’m trying to understand why even white people would want to be in this place, let alone me.” Then she looked over and saw “this big, burly white guy stopping me from getting in.” In that moment, she found herself face to face with a proud representative of white supremacy, a man committed to the oppression of Black people.

“Seeing this white guy stopping me from going into this public institution, it gave a face to these smaller slights I’d experienced in Tarrytown, New York,” says Richardson. “It’s only then that I see: this is racism. And more important, I now have a constructive vehicle through which to fight that racism, and that vehicle is SNCC.”

Richardson began taking the bus down to Cambridge almost every weekend. She met Gloria Richardson (no relation) who was among the Black Cambridge leaders who founded the Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee, and Reggie Robinson, the SNCC field secretary in Cambridge. She also had her first experiences getting arrested for civil disobedience and spending time in jail.

One day, Richardson was approached by a fellow student named Penny Patch. Patch had just returned from taking a semester off to participate in the Southwest Georgia Project of SNCC. Patch, who is white, told Richardson about their work registering disenfranchised Black voters in the rural districts of Southwest Georgia, which often were majority Black yet concentrated power in the white minority.

“Penny had been in this project,” Richardson explains. “Now she’s back. She hears that I’ve been getting arrested and I’ve been going to Cambridge. She comes to my dorm room and she says, ‘Look, why don’t you think about taking off the next semester’—which would have been the first semester of my sophomore year—‘take that off and go work for SNCC in Cambridge.”

Because she was from the north, Richardson had to fill out an application. If accepted, she would make $10 a week for the work—$9.64 after taxes. Soon, says Richardson, “Penny comes to me in my dorm room and says, ‘You’ve been accepted.’” The gears were set in motion. She talked to the Swarthmore administration and confirmed she could take a year off and keep her full scholarship.

Then it was time to make the plan official. “I screwed up my courage and called my mother,” says Richardson. “I’ve been dreading this, right? But she doesn’t do anything. She’s fine.”

Twenty minutes later, one of Richardson’s dormmates called out, “Judy! Hall phone!” She picked up the phone to find it was her sister. “She’s screaming at me, right? And she says, ‘What are you talking about? You can’t do that!” She’s going off.” Her sister, who was nine years older than her and working for Columbia Records in New York City only calmed down once Richardson reassured her that she would keep her scholarship. (Within two years, her sister, too, had left her job to join SNCC, working among other roles as the coordinator for the SNCC fund-raising house parties that Harry Belafonte gave on Long Island during the summer of 1964. “That’s what good movements always do,” says Richardson. “They bring family members in.”)

Richardson finished her spring semester and followed through on a summer job she already had lined up. Then she moved to Cambridge and began working for SNCC full-time. Things moved quickly. In November she visited SNCC’s central offices in Atlanta, and when SNCC’s Executive Secretary, Jim Forman, learned that she was a fast typer and knew shorthand, he asked her to stay in Georgia and act as his secretary.

It gave her a birds-eye view of the many functions of the national office, as well as the various SNCC national networks: Friends of SNCC, Campus Friends of SNCC, the communications department, research department, photo department, pro bono lawyers, etc.

SNCC was the least sexist of the civil rights organizations, with female leadership that included Ella Baker, the legendary strategist and main SNCC mentor; Diane Nash, the leader of the Nashville student movement; and Ruby Doris Smith (Robinson), the office administrator, who coordinated the national office and SNCC’s field organizing in Mississippi, Alabama, Southwest Georgia, and Arkansas. Richardson was soon sitting in the highest-level meetings of the organization—and at one point leading her own sit-in at SNCC’s offices to protest the organization’s de facto policy of only having women members take meeting notes. The intra-organization protest succeeded; male members began sharing in that work. SNCC’s non-hierarchical grounding encouraged both leadership and protests among female staffers.

Richardson extended her year off from school. In 1964 she moved, along with SNCC’s National Office, to Greenwood, Mississippi. There she helped organize Freedom Summer, a voter registration drive that attacked Jim Crow head-on by trying to register as many African-American voters as possible. Their work was grounded in the decades of organizing that had already been done by Black leaders in Mississippi, at great risk to themselves and their communities. And it was these local leaders who guided—and guarded—SNCC workers and other organizers.

Part of the strategy included bringing primarily white college students from throughout the country to help with the work, with the clear intention of bringing nationwide visibility to their cause. One devastating chapter ended when the bodies of the three civil rights workers who were missing at the moment of Richardson’s hospital standoff—James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner—were found dead, 44 days after their disappearance, buried in an earthen dam. They had been murdered by at least ten white men, including a deputy sheriff and members of the KKK.

These young men’s disappearance—and the search for their bodies that the FBI was pressured to launch—became front-page news in national newspapers, and the outrage around these murders, as well as coverage of Freedom Summer at large, helped bring broad awareness to the movement. And these murders have had a long aftermath. The family of Andrew Goodman eventually founded the Andrew Goodman Foundation, dedicated to bringing young voices and voters into our democracy. Today the foundation’s president is Andrew’s brother, David Goodman ’69 (College, BA), who has spent decades working to increase voter registration, particularly among youth.

For Richardson and the other veterans of Freedom Summer and the Movement generally—including workers from CORE (the Congress of Racial Equality), SCLC (Dr. King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference), and the many local organizers—their work went on. The next year, she initiated the idea of a Residential Freedom School that brought high school students from the North and South together in Chicago, IL and Cordele, GA, to share their passion and bring new energy into the movement. She also organized with Stokely Carmichael and Bob Mants in Lowndes County, AL, then moved back to Atlanta to help manage Julian Bonds’ successful first campaign for the Georgia House of Representatives. By the time she returned to college in 1966—this time to Columbia University—she had spent four years playing a key role in the fight against white supremacy in the U.S.

“Seeing this white guy stopping me from going into this public institution, it gave a face to these smaller slights I’d experienced in Tarrytown, New York. It’s only then that I see: this is racism.”

Richardson grew up on the banks of the Hudson River, a short drive north from New York City. “It’s Westchester County,” says Richardson. “Some considered it a commuter town, but for me, it was a factory town, dominated by ‘The Plant’: the factory that made parts for Chevrolet cars. I’m in the poor section of Tarrytown, where there are other Black folks, Poles, Irish, and Italians.” Most of her young classmates came from this multi-cultural milieu, she says. “And all of their fathers worked, as my father did, at the plant. In fact, my father helped organize the United Auto Workers union, the local at the plant.”

Then, when she was seven, tragedy struck. “I get pulled out of class,” explains Richardson. “It turned out that he had a heart attack and died on the line.” At the time, he was treasurer of the UAW local.

This left Richardson’s mother as a single working parent. Despite only having an 8th-grade education, she was vibrantly “in the world,” says Richardson, keeping up with world events through newspapers and the nightly news, and playing “a mean jazz piano.” She managed to send both of her daughters to college—Richardson to Swarthmore and her sister to Bennington College.

Throughout Richardson’s involvement in the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, her mother’s support manifested in various ways. She sent newspaper clippings to keep her daughter informed, and she even wrote her own letters to the editor responding to right-wing articles that smeared SNCC as communist sympathizers. While she didn’t voice her worries directly, her personal letters to her daughter revealed the sleepless nights she endured, concerned for her daughter’s safety—especially when Richardson went to Mississippi. But Richardson didn’t realize fully the depth of her mothers concern until she re-read the letters years later. Young adults often think they’re invincible, but with a more mature perspective she came to understand how hard it must have been for her mother to know the risks she was taking and not ask that she leave SNCC.

Richardson has followed in her mother’s footsteps by cultivating her own practice of keeping up with current events via newspapers and clipping articles. She has significantly drawn upon this practice in her work in various ways, including when she worked as the Director of Information for the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice in midtown Manhattan. Her position included writing a weekly commentary on current events, sourced from newspapers such as institutions of the Black press, like the Amsterdam News, Pittsburgh Courier, and Chicago Defender, and mainstream paper like the New York Times, Washington Post, and New York Newsday. The commentaries were recorded and sent out to various media outlets via audio tape and mailed hard copy.

Recently, Richardson was reflecting on her practice of responding to news items and realized that this practice was a direct inheritance from her mother. In particular, her mother wrote letters to the editor of the local paper, the Tarrytown Daily News, responding to the letters of another woman in town, a Mrs. Kenny. As she remembers, “My mother, who had an eighth grade education but was absolutely informed, in the world… would write these letters in response to Mrs. Kenny. I still have those letters. She would then send me the clippings that she had, of her letter and Mrs. Kenny’s letter.”

Judy’s Advice for Activists of Any Era and Age

The work for social change may not show results within one’s lifetime. However, activists over the years have worked for the benefit of future generations, not expecting to see the results themselves.

Surround yourself with people who also believe that you can fight white supremacy and economic injustice and make life better for all folks. My continuing work with the SNCC folks I’ve known for 60 years—through the many intergenerational projects initiated by our SNCC Legacy Project—keeps me energized and helps me get out of bed every day.

We need to continue the work, even if we don’t see the possibility of immediate success. We need to always continue to struggle. If we fight, we win.

Use the vote. It is not the only tool in the toolbox, but it is an important one. We don’t have billionaires supporting us, so the vote can be a critical equalizer… if we use it.

Take a holistic approach and value things that may not seem directly related to ‘the cause.’ Cultivate joy and a sense of purpose in whatever community you’re operating in.

Respect everyone. The beloved community ethos involves respecting people regardless of their background or social status. This was particularly important for SNCC when organizing in communities with varying levels of formal education and relative wealth. It’s still important today.

Sometimes change comes from unexpected sources or in unexpected ways.

Celebrate small victories.

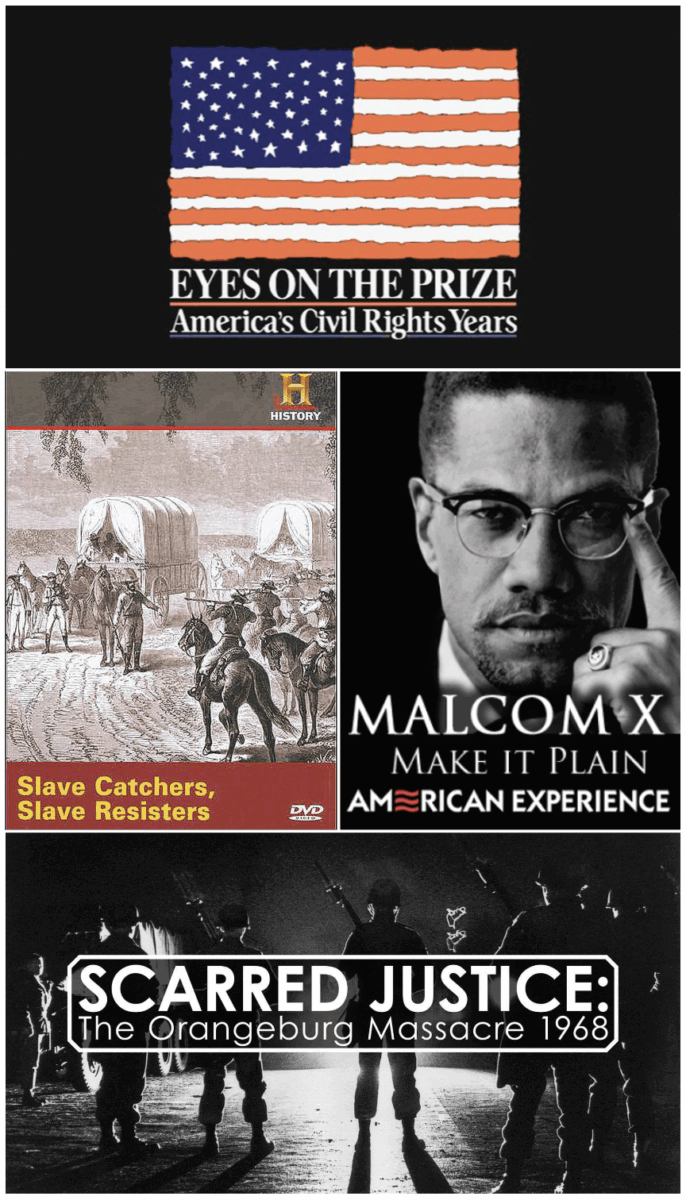

Richardson emphasizes the critical importance of accurate documentation in her work, particularly in the context of creating historical documentaries. This was particularly important when, in the mid-’80s, she started working as a researcher, series associate producer, and content advisor on the project that would become Eyes on the Prize, a 14-hour PBS documentary TV series about the Civil Rights Movement (1960-1980) that went on to win several Emmys, the du-Pont Columbia award, and was nominated for an Oscar for Best Documentary.

The series’ creator and executive producer, Henry Hampton, was also the founder and head of the production company Blackside. “One of the things that Henry understood was, this is a Black film company,” says Richardson. “He is a Black man. They will try and say that it is biased, that this interpretation is biased. And so a couple of things happened. One is, there were no re-creations. Everything that you see in Eyes actually happened. It is real footage.” And their approach to that footage was meticulous. “If you see footage that we identify as related to a demonstration—say, Birmingham, March 13th, 1963—that footage has to be of March 13th, 1963. It cannot be March 14th, 1963, right? March 13th. So we never saw a B-roll as generic. It was always specific to exactly the thing that we were talking about.”

The documentation process had a level of detail more often suited to academic monographs. “We had a Fact Book, and that fact book was for each program,” she says. “And on the back of each page of scripts, we had citations for every point, both in the interview and the narration—anything that could be questioned by critics.”

The original working title for the show was America, They Loved You Madly. This title held through the early stages of the project’s development. However, Richardson made her dislike of that title known, even when she was the sole staffer. When more staff was hired in 1979, Richardson sent out a memo (of which she has kept a copy) that included a list of freedom song titles, including “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize.” Hampton took this suggestion and shortened it to simply Eyes on the Prize. This title has since become iconic and synonymous with this landmark documentary of the American Civil Rights Movement.

Richardson has worked on many films since, including Malcolm X: Make It Plain, Scarred Justice: Orangeburg Massacre 1968 for PBS, two History Channel documentaries on slavery and slave resistance, and installations for, among others, the National Park Service’s Little Rock Nine Visitor’s Center, the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, the New York State Historical Society’s “Slavery in New York” exhibit, and the Paul Laurence Dunbar House. She just finished co-directing a visitor center film for the National Park Service’s Frederick Douglass House in Washington, DC. and is working on films for a number of Black history museums, including those in Memphis and Atlanta, and the National Museum of African American History and Culture on the Mall.

Decades before her work for Eyes on the Prize, Richardson explored how narrative and visual storytelling could expand minds and hearts in a different direction—as a bookseller. In 1968, she moved to Washington, DC, to help start a bookstore dedicated to literature from Africa and the African diaspora. She and a few other SNCC veterans soon opened the doors of Drum & Spear Bookstore, which became the largest such bookstore in the country and a hub of Black literature and culture, hosting readings by authors including Gwendolyn Brooks, Lerone Bennett, Shirley Graham DuBois, Haki Madhubuti, and Sonia Sanchez. During her time at Drum & Spear, Richardson established the children’s literature section. It was one of the most popular sections in the store.

In association with their work at Drum & Spear, Richardson and her SNCC colleagues also produced a radio program, “Saa ya Watoto,” on WOL, which she hosted as “Bibi Amina”. She and her colleagues adapted stories from Black children’s literature into plays, and they incorporated Swahili language and folktales. They also organized Drum & Spear Press, which published children’s books featuring stories told from African American perspectives, and they visited classrooms to give literary performances in person. The Press also published books about African American history and a Palestinian poetry book.

Years after the show went off-air, Richardson was being interviewed by a young woman who was participating in a summer program at Harvard. The woman knew of Richardson’s connection to “Saa ya Watoto,” and she told Richardson about how clearly she remembered how, when she was in the third grade, Richardson had visited her classroom, dressed in African attire and reading folktales.

Later, Richardson built on this work by conducting a study for Howard University on racism in children’s books with Black subject matter. The study, which analyzed representation in children’s literature, was later published in the Journal of Negro Education, a publication of Howard’s graduate School of Education. And in the late ’70s it became the basis for her application to Antioch’s General Studies program.

Richardson was accepted, and she enrolled at Antioch’s Maryland campus in a degree completion program. While she had many, many real-world experiences and skills—and had completed coursework not just at Swarthmore but also at Columbia University—she still did not have a bachelor’s degree. Antioch provided a way for her to earn her undergraduate degree that no other institution could have at that time in her life. The college valued and credited her real-world experience and skills, and the degree from Antioch opened many professional doors for her.

“There is no other way I would have gotten this undergrad degree at that point, except through Antioch’s night classes—no other way—because they understood life experience, the skills I was bringing in,” Richardson says. This degree opened doors, including, down the road, an appointment at Brown University, where she served as Distinguished Visiting Professor in of Africana Studies. In 2012 she received an honorary doctorate from Swarthmore. As Richardson says, “I would never have been able to teach at Brown University had I not gotten that undergrad degree…. Would I have even gotten in the door at Brown had Antioch not given me that chance? You know, I don’t think so.”

“Would I have even gotten in the door at Brown had Antioch not given me that chance? You know, I don’t think so.”

Today, after many decades fighting for racial and social justice, Richardson remains deeply involved in civil rights work. A key part of Richardson’s work in recent decades has been to ensure that the memory of these movements is preserved—and passed on to the next generation. She does this through her filmmaking, and also by taking an active role in both the SNCC Legacy Project and the SNCC Digital Gateway. Some of this work has meant putting together extensive resources and toolkits with the support of funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities. One conference she directed brought activists from younger generations together with SNCC veterans. Another brought six activist organizations to work with a Black archivist at Duke University to impress on them the importance of documenting their own history.

Carrying on this work also means taking action as events warrant it. When the board of the SNCC Legacy Project put out a statement on February first of this year, Richardson narrated the video version. “Our own experiences as Civil Rights Movement veterans leave us without illusions about the capacity of tyranny to take root,” she says, as images from the 1960s Civil Rights Movement cross the screen. Her steady voice continues, “Today we see a national government taking shape that is reminiscent of the white supremacist Citizens Councils in Mississippi and throughout the South. And we remember that their viciousness was not only directed at civil rights activists and organizers, but at all people who criticized or stood in dissent of their practices and programs.”

One last story from 1964 and the Freedom Summer campaign in Mississippi. Richardson and about twenty other civil rights workers had been in jail for five days. While locked up, they had gone on a hunger strike. Finally they were released, and a local church welcomed them with food and song.

“Must have been about twenty of us—male, female, SNCC workers, SNCC staff—and we’re coming into this church,” Richardson recalls. “And I hear this wonderful gospel choir, right? And they’re singing one of the freedom songs. You know, ‘Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me ‘Round.’ And they’re singing in this great harmony. We’re coming in, and people are up on their feet, and they’re clapping, and the music is lifting me up. But then there is the aroma of fried chicken. And it is fried chicken in the way that you only get in a Black church in the South, you know? We’ve been on a hunger strike for five days, and it just lifted me up. And I’m not religious, right? But it was the music and the sense of community and this sense of support from the church for what we were doing.”

What I most took away from my conversation with Richardson is the understanding that when it comes to a movement, seemingly small or tangential efforts matter a great deal. The regular people who show up and contribute their time and energy are as important as charismatic leaders. Continuing to be involved and invested by lending one’s unique strengths and skills to a cause over the long term is of great value, even if it might not generate a splashy headline. Especially in the midst of overwhelming times, contributions like this are crucial. Despair is not an option, which does not mean one can’t feel sorrow or struggle or step away for a beat if needed. After all, SNCC provided mental health support for their staff. It just means that if we don’t like where we are, keeping on going is how we get to somewhere else. Hopefully, somewhere better.

The opportunity to speak with Judy Richardson was a gift. Her stories and practical advice for cultivating a sustainable, realistic approach to activism have lent me, personally, renewed energy for the practice of this thing we call hope—hope as an act that needs to be renewed on a daily basis. Hope in this context isn’t just a feeling but an approach to activism and social change. It’s about finding ways to make progress and stay motivated, even when faced with daunting obstacles. In Richardson’s view, hope coexists with a clear-eyed view of reality. It’s not about ignoring problems but about finding our own ways to address them, little by little, step by step. Call on your strengths. Do what you can. May these stories be useful.