August 9, 2023, was a notable day for Julie Ann Sa’Leit’Sa Kwina Johnson ’81 (Seattle, BA). The Mayor and City Council of Seattle had proclaimed the day “Auntie Julie Johnson Day” in her honor, and across social media there was an outpouring of love and appreciation for Johnson from elected officials, community leaders, and friends. Seattle’s Mayor, Bruce Harrell, called her a “visionary leader.” U.S. Senator Patty Murray noted that Johnson “has worked tirelessly to make sure Native voices are heard in Washington state government and across the country—and she’s made a real difference.”

This was a shining capstone for Johnson’s decades of commitment to amplifying Indigenous voices in the halls of government—but it wasn’t a retirement plaque. The next day she kept on with her work. And she continues to be prolific in her service: she’s co-chair of the Native Vote Committee of the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians, which represents 57 tribal nations; she’s on the Executive Board of the Northwest Indian College Foundation; she’s Chair of the Native American Caucus of the Washington State Democratic Party, where she’s also on the Executive Committee; and she’s the President of the National Indian Women’s “Supporting Each Other” Honoring Lunch, an annual event held in Washington, DC, that she founded 28 years ago.

“There is so much talent and competence in the Native community,” says Johnson. She herself is an enrolled member of the Lummi Tribe, and her work has helped her understand the key role that tribal nations play not just in the history of her state but also in its present. “When you look at employment in Washington State,” she says, “the 29 federally recognized tribes in Washington are, combined, the fourth-largest employer in the state.”

Despite this considerable economic power, historically there have been few candidates from the Native community. To Johnson, this is a problem. “Indian people need to get behind those desks and advocate,” Johnson says. “We’ve been donating to non-Indians for years. We need to support our own people for public office, too. I want our people in those chairs.”

Her work has been paying off. In last year’s elections, a historically large number of Native candidates ran for Washington State higher office, including five candidates for State Senate, three for State Representative, and one for Commissioner of the Department of Natural Resources. A decade ago, Washington State had only a single Native American politician serving in the statehouse. Today, there are three.

“We’ve been donating to non-Indians for years.

We need to support our own people for public office, too.

I want our people in those chairs.”

Johnson grew up on the Lummi Reservation for the first years of her life. When she was only five years old, her family house burned down. She experienced a time of dislocation, including spending time living in the home of her great-grandfather, Henry Kwina, the Chief of the Lummi Tribe. Her father eventually found a job in Neah Bay, on the Makah Reservation in far north-west Washington, and her family moved there. She’s lived in that area ever since.

Her experiences growing up instilled in her a deep understanding of many of the challenges facing Indigenous communities in North America. This became part of her career in the late 1960s, when she began working running a youth program in Seattle, working with at-risk youth and helping place Native children in foster care in support of the Indian Child Welfare Bill. Around that time, she joined the American Indian Women’s Service League (AIWSL)—the first group in Seattle dedicated to tackling the issues facing urban Native folks. She was mentored by the organization’s co-founder, Adeline Garcia, and served as its treasurer and later president.

By 1980, Johnson had been doing important work in her community but still lacked a bachelor’s degree—despite having completed coursework at institutions including Evergreen State College and the University of Washington. That fall, she began taking classes at Antioch University’s Seattle campus. This required a three-and-a-half-hour journey from Neah Bay, but she was driven with a profound sense of purpose—and a desire to follow her interests. As she explains, “I wanted to learn how to recognize the accomplishments of our Native people and how our leaders had survived and worked in both worlds: the non-Indian world and our traditional Native world.”

Antioch allowed her to count credits from her past coursework, and she ended up putting together a degree in Educational Council and Social Services Administration with a minor in Economic Development. She graduated in 1981. “Antioch helped me to recognize my own ability to be positive, to plan, to organize and be persistent, to recognize the accomplishments of others,” says Johnson. It also equipped her to “inspire our young Native women to seek leadership positions and make positive change… and step away from the oppression and negative attitudes of not only our people but also in the non-Indian world.”

Completing her degree set Johnson up to continue her career in public service. She went on to serve as Planning Director for the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe and Senior Grants Writer for the Makah Tribe. In the latter role, she secured over $20 million in federal and state funding for critical infrastructure and community projects. Her work facilitated transformative initiatives, including senior programs, Head Start initiatives, and the historic removal of the Elwha Dams and restoration of the Elwha River. Two decades after her graduation, in 2001, she was honored by recognition as one of the “Distinguished Alumni” of Antioch University.

While Johnson’s work has always intersected with politics, her engagement with elections and political campaigns really began in 2008, when she attended a local Democratic Party meeting. She quickly realized that there was a need for Native voices in government decision-making positions. When later she put her name forward to be Treasurer of the Washington State Democratic Party, and was elected to that position, she became the first Native woman ever to serve in that role since the party’s establishment in 1890.

Johnson has dedicated herself to advocating for Native perspectives both within the Washington State Democratic Party, as Chair of its Native American Caucus, and also as co-chair of the Native Vote Committee of the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians. In this latter role, she has developed innovative advocacy strategies. Without the budget to hire a team of traditional lobbyists, she has organized “Listening Sessions” that bring tribal administrators together to prepare for governmental meetings. Her approach focuses on education and systematic inclusion, challenging widespread misunderstanding of tribal treaties and sovereignty. The discrimination and lack of understanding about tribal treaties and sovereignty that Johnson has witnessed over her lifetime has led her to a dedication to changing these systems from within.

She also has a national impact through her founding and leadership of the annual National Indian Women’s “Supporting Each Other” Honoring Lunch. The phrase “Supporting Each Other” comes from Native activists in Seattle in the 1960s, and it foregrounds the importance of solidarity for leaders who have shared identities as both women and Native Americans. The event, which always takes place during the annual meeting of the National Congress of American Indians, is a chance to build connections and celebrate each other.

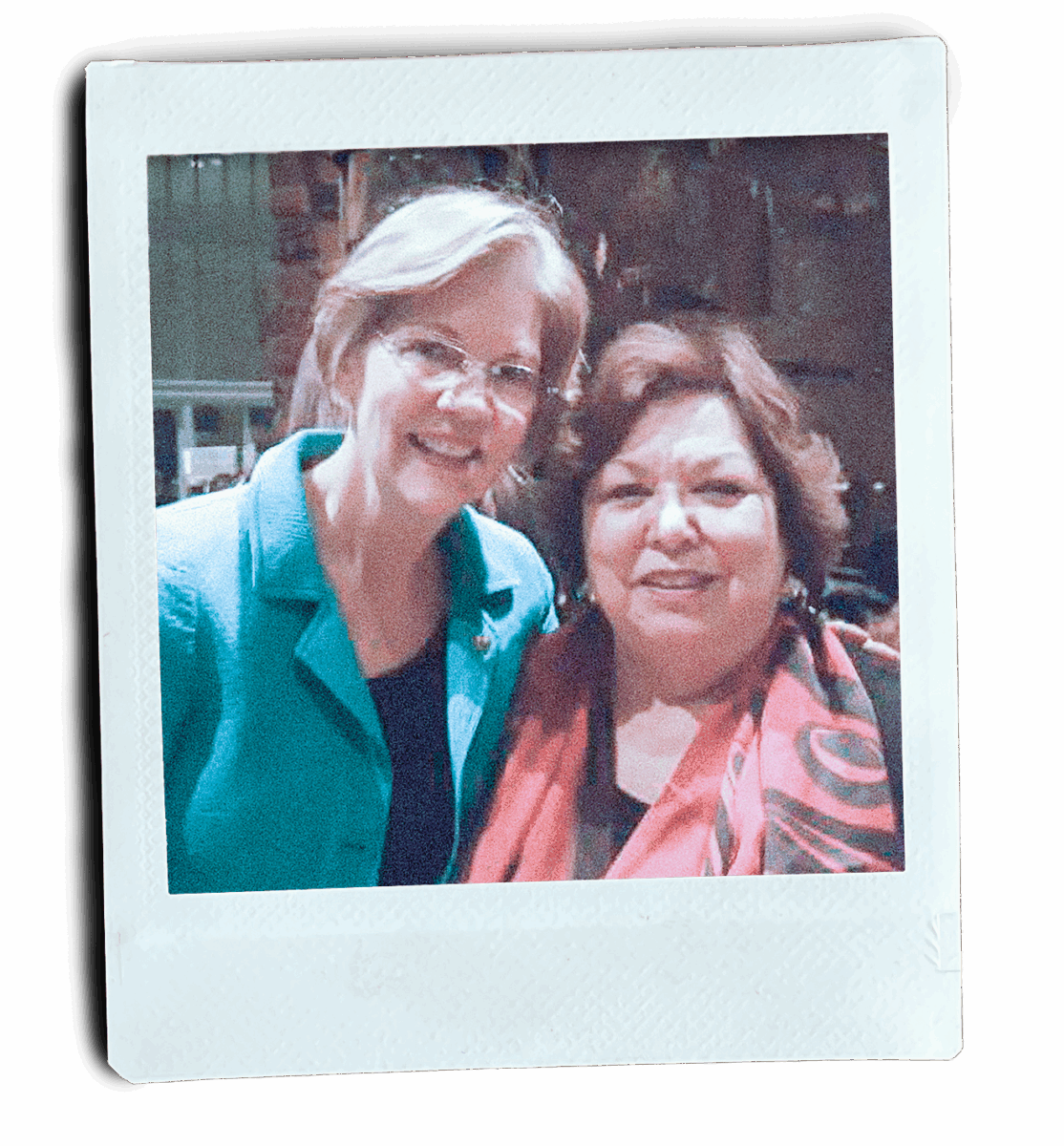

The lunch organizers always recognize two Native women who are making an impact in Indian country. They also welcome prominent female politicians as special guests. Recently these guests have included Senator Elizabeth Warren, then-Senator Kamala Harris, Minnesota Lieutenant Governor Peggy Flanagan, and then-Representative Deb Haaland. Haaland, who herself is an enrolled member of the Laguna Pueblo tribe, went on to serve as Secretary of Interior in the Biden administration. The Department of the Interior runs the Bureau of Indian Affairs, oversees the National Parks Service, and directly manages about 1/5 of the surface area of the U.S.; Haaland was the first Indigenous American ever to run the Department.

Last year, in mid-December, Johnson traveled to the state capital in Olympia—this time in her role as one of 12 Democratic party electors from the State of Washington. She was one of 538 electors across the country who came together to participate in the Electoral College. Because Kamala Harris had won the state’s vote in the Presidential General Election, Johnson was legally obliged to cast her electoral vote for Harris. And she did so proudly, voting for the first woman of color ever to run for U.S. President on a major party ticket.

Even as she participated in the ceremonial Electoral College, she knew that Harris would not be assuming the Presidency. Instead, Donald Trump would be returning to the White House. Secretary Haaland would be leaving the Department of the Interior. And a much less diverse administration—only 17% of cabinet nominees were non-white, compared to about 44% of the U.S. population—would be taking the reigns of the federal government. There would be more work to do, both as a Democratic Party leader and as someone committed to increasing Native elected representation in Washington State and around the country.

This work isn’t something one person can do alone. It takes many hands. As new generations of Native leaders step forward to address the challenges of today, they continue to have the support and example of their “auntie,” Julie Ann Sa’Leit’Sa Kwina Johnson. As Deborah Parker, a close colleague of Johnson’s and former Vice Chair of the Tulalip Tribes, says, “Julie has been tireless in bringing forward the voice of all people, especially our Native American men and women. She has inspired our young Native women to run for office and fight for representation.”