With a traveling museum and a passion for conversation, Delbert Richardson is sharing “American history through an Afrocentric Lens.”

“You look at Black inventions like the Super Soaker, the doorknob, ice cream scoop, and pencil sharpener—the inventors are Black superheroes,” says Delbert Richardson ’16 (Seattle, BA). “The superpower,” he says, “is brilliance and creativity.” He often gives this talk to schoolchildren, encouraging them to tap into their own creativity as their superpower. And he likes to add one more piece of wisdom: “It can only be a superpower if it helps someone else or other people.”

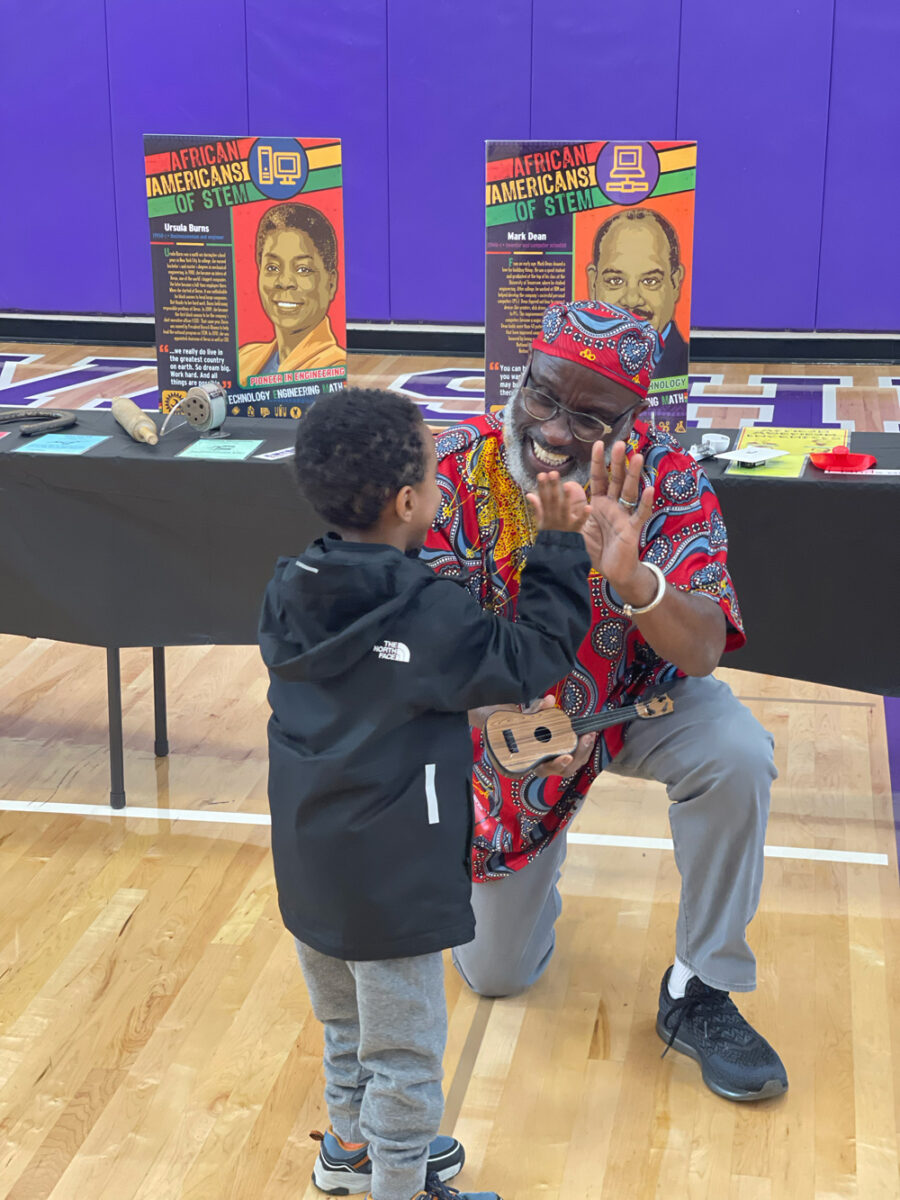

Richardson practices what he preaches. He has devoted much of his labor and resources to creating and touring with what he calls the American History Traveling Museum: The “Unspoken” Truths. A one-of-a-kind production, this nationally award-winning traveling museum is largely made up of objects from the continent of Africa and from American history, including shackles that were once used to confine enslaved Black people Ku Klux Klan robes, signs enforcing segregation from the Jim Crow South, and pieces of Black Americana like Aunt Jemima syrup bottles. Simultaneously, the museum celebrates Black excellence, including a forty-foot display of everyday items that African Americans have invented, patented, or improved upon. (For instance, the pencil sharpener.) Most of all, it includes Richardson himself, who acts as docent, historian, and, as he describes himself, “second-generation storyteller.”

In a society that hasn’t fully reckoned with its own white history—and present—of racialized oppression, Richardson has spent the last two decades refining his museum and bringing it into K-12 schools and other public places, including, last year, a stage show. His central work is to bring forward parts of history that our educational systems and broader society often work to conceal. “My work is around awareness,” explains Richardson. “I’m not here to change anybody’s mind, anybody’s beliefs.” I’m here to provide an opportunity to create a healthy space for sometimes difficult conversations, and hopefully the result is that you’re willing to do some more around self-discovery work.”

For Richardson, the work of grappling with what it means to be Black in America goes back to the first time he heard fellow African Americans use that term, “Black,” as their racial identity. It was 1973, five years after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Richardson an undergraduate at the University of Washington in Seattle. At first it sounded strange. “In my neighborhood, if you call me ‘Black,’ we were going to fight,” says Richardson. As he explains, “I had been socialized that Black was a negative term.” But he had an open mind, and soon he learned that these students had made a decision as to how they wanted to be seen. He says, “What I grew into is that these students had made a decision that they wanted to affirm themselves by calling themselves Black.” Richardson joined them. “I was transformed from being a ‘negro’ to affirming myself.”

This experience would end up being a catalyst for Richardson’s journey as an educator—but not quite yet. As it turned out, Richardson ended up leaving college before graduation. In the world of work, he eventually landed at a new company that had recently been founded in a suburb of Seattle: Costco. It ended up being a good place to make a career. He stayed at Costco for decades, slowly moving up in the company.

While traveling for work, Richardson found himself drawn to Black memorabilia shows and antique shops. Eventually he started collecting, and he found that this connected him with his interest in his Black identity. On one trip, he bought a pack of black inventor flashcards, a Ku Klux Klan robe, and an authentic pair of slave shackles. These would each go on to be part of the traveling museum, but at the time, when he returned to Seattle, he didn’t really know why he had bought them. As he puts it, “I found myself at home with a bunch of items, not really knowing what I was going to do with them.”

In the teens, after retiring from Costco, Richardson decided to return to school and finish his Bachelor’s degree. Through a connection with longtime Antioch faculty member Marcia Tate Arunga, he decided to enroll at Antioch University’s Seattle campus. He was able to receive significant college credit for documenting his life experience, and he developed the language and confidence to claim his knowledge and research. He started calling himself a community scholar.

This was also the time he started seriously developing the idea of the traveling museum. He leveraged his background in sales and demonstrations from Costco to develop a show where he could use his artifacts to educate youth and adults. He leaned into the insight that everyone learns differently, whether by touch or sound or reading or responding, and he decided that he would include his students in the evolution of Black history.

“I knew that I was going to primarily teach Black and Brown kids in schools, Pre-K to 12th grade,” says Richardson. He would take the museum into both classrooms and to school assemblies. He says that “American History is the box,” and it’s his job to open the box up and reveal some of the pieces that often get overlooked or erased. “I call it American history through an Afrocentric Lens.”

Richardson decided to condense the long history of Black America into four quadrants. This gives the show a chronological timeline. The first quadrant, “Mother Africa,” accounts for many of the contributions that Africans have made to the world. The next, “U.S. Chattel Slavery,” breaks down the type of slavery where humans are considered to be property. “Jim Crow” explores the racial caste system revolving around white supremacy. And lastly, “Still We Rise” gives a thorough and inspiring accounting of inventions and contributions from African Americans.

Richardson doesn’t consider the show as being exclusively for Black youth. “When I go to a school and I’m in front of Native Americans, Latinx, Asian Americans, Polynesian Americans, I ask them to replace Mother Africa with your own country,” he says. “We have something in common as being melanated people. Rich culture, heritage, and tradition. We also share being oppressed by the dominant culture.” And for white students, too, it can be powerful to learn the history and effects of white supremacy, and the often-hidden history of African and African American contributions.

He’s not only teaching students about Black history, he’s pulling back the curtain on years of oppression done to millions of people and their cultures. He tries to remind students that they’ve been assimilated into the supremacy of white culture in America. And they can resist that assimilation.

Richardson has found success with the traveling museum, reaching thousands of students while also gaining coverage in the press. In early 2020, he was preparing for his most ambitious plan yet: to bring the traveling museum for a multi-stop tour of Africa. Richardson’s goal was to re-educate people on the African continent. Unfortunately, two days before departure, the COVID-19 Pandemic shut down air travel. The plan had to be scuttled.

Nonetheless, Richardson managed to extract something good from this disappointment. On a walk with Vida and Steve Sneed, they hatched the idea of turning the traveling museum into a stage play. And last year, at Seattle’s Intiman Theater, this came together as The Lion Tells His Tale, an adaptation of the museum with dancing and song. Richardson played the starring role.

Becoming a lead actor wasn’t something he had really planned for—but external reviewers of early drafts of the show strongly suggested it be revised to give him a bigger part. The director, Vida Sneed, asked him if he would play the role. “I said no,” remembers Richardson, with a laugh. He then added, “But if that’s what you want me to do, I’ll do it.”

Richardson says that he experienced “a lot of fear, anxiety, and a lot of self-doubt.” As he puts it, “I’m not an actor, until I get on stage, until I start storytelling, and then the ancestors speak through my mouth.”

“I’m not here to change anybody’s mind, anybody’s beliefs. I’m here to provide an opportunity to create a healthy space for sometimes difficult conversations. And hopefully the result is that you’re willing to do some more selfdiscovery work.”

Richardson likes to describe himself as a second-generation storyteller, a way of acknowledging his father, who lived through the Jim Crow era and kept this cultural memory alive through the stories he told. Richardson intends for his work to honor his parents. “What it does,” he says, “is it sets in motion—who’s the third generation? Who’s the fourth? Fifth? And so on.”

In touring his traveling museum, Richardson encounters people with many different backgrounds and beliefs. He always encourages them to do research. “Things are constantly evolving,” he says. “I love people challenging me. I love it when somebody comes to me and gives me information.” He considers himself to be a life-long student. And in times like these, both socially and politically, he stresses how important it is that we learn about our past so that we don’t repeat past mistakes. As he says, “I know for a fact that my work is probably needed more than ever.”