A half-century after helping open Antioch’s Los Angeles campus, Al Erdynast is still looking forward to what comes next.

Al Erdynast has been at Antioch University’s Los Angeles campus since the beginning—almost. Before his arrival, the fledgling campus met in Mel Sudh’s Los Angeles living room and was attended by eight students. But on August 1, 1973, it officially opened as an accredited part of the Antioch Network, with Al Erdynast as its director. And in one role or another he’s worked in the university for the last fifty years. Today he is still teaching here—and still embodying the integrity that has been his guiding principle as a teacher and administrator promoting effective, inclusive, progressive education.

Erdynast had just graduated with a PhD from Harvard Business School when Lance Dublin, director of Antioch West, which included Los Angeles and San Francisco, hired him to head the new undergraduate programs in Los Angeles. The goal of the newly-accredited program was to grow and become integrated into the larger community of Los Angeles. As director, Erdynast hired eight faculty in his first week, but for financial reasons was only able to hire them on a quarter-time basis. At the time, tuition for full-time students was $333 per quarter. Resources were scarce, and he had to be creative to find students and publicize offerings.

His efforts paid off and the campus quickly grew. In its second year, the program grew to around twenty students, and a year later it was serving over one hundred undergraduate students. It was well on its way to becoming the thriving school we know today.

A Unique Approach to Adult Education

Erdynast jokes that in his early days at the Los Angeles campus he was accused of being “traditional” because he bought chairs with arms to replace the LA campus’ then-standard form of seating: the bean bag chair. But his big work was helping create a re-entry program for adult students who wanted to complete a bachelor’s degree. For this, his doctoral research in moral development was helpful, as he sought to bring Antioch’s educational excellence to students who often had been left behind or deliberately excluded from higher education.

In those years, the median age of students in the BA completion program was 36. Administrators and faculty faced the question of how and whether they could award academic credits for life experience. Figuring out how to make that work was essential to helping students actually complete their undergraduate degrees. And many policies developed in that period still stand in the undergraduate programs at the Los Angeles campus. Today, the campus does serve a greater number of young adults, but most students are still older than traditional undergraduates.

BA students continue to be drawn by Antioch’s reputation for developmental adult education. After graduating, students are prepared and credentialed to enter spaces they may previously not have had access to. Erdynast is particularly proud that, between the years of 1968 and 1975, twelve graduates of the BA program went on to be admitted to graduate study at Harvard University, his alma mater. “Our students have gotten in everywhere,” Erdynast says.

Masters Programs of National Recognition

One student who went on to get her Master of Education and Doctor of Education degrees at Harvard was a BA graduate named Cheryl Armon. Armon’s doctoral dissertation was considered one of the most important examinations of adult moral development in twenty years, says Erdynast. After graduating with her doctorate, Armon returned to the Los Angeles campus, where she served as chair of the BA in Liberal Studies Program and then developed, founded, and chaired the campus’s graduate education program.

This specific expansion into graduate education wasn’t unusual. Over the years, the LA campus has developed many programs including a Masters in Organizational Management that Erdynast helped develop and taught for many years.

Another graduate program that Erdynast was around to see launched is the Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing. At its inception in the late ’90s, the noted poet (and later, first Los Angeles Poet Laureate) Eloise Klein Healy was faculty in the BA program at Antioch. She had the idea and follow-through to found Antioch’s first low-residency program—a master’s program where students meet on campus only twice a year, for ten days at a time, and otherwise correspond with mentors at a distance. Klein Healy successfully designed and started the MFA, which has the distinction of being the first low-residency MFA in Creative Writing program ever to exist on the West Coast and was among the first in the nation. Today, the MFA program continues to serve students from around the country as well as international students. MFA graduates include many notable writers, and it is widely acknowledged for providing a rigorous literary education with a special focus on social justice and literary citizenship.

The biggest program to be started at Antioch’s Los Angeles campus in the last fifty years is the MA in Clinical Psychology. This large and in-demand program counts among its graduates thousands and thousands of California therapists.

Erdynast, however, remembers how the program was almost nipped in the bud before it even started. This was back in the ’80s when Joe McFarland was running Antioch West, the unit of Antioch University that at one point contained not just the Los Angeles campus but also campuses in Seattle, Los Angeles, Hawaii, Corpus Christi, and North Slope. McFarland replied that he had opened a single center with eighteen branches.

Despite his quick rejoinder, the questioning seemed to give McFarland cold feet, and consequently, he came to the brink of canceling plans, then in the works, to found the program that became the MA in Clinical Psychology. Emergency meetings were held. Impassioned pleas were heard.

Ultimately, the new program did get launched. The timing turned out to be perfect. Its launch coincided with a boom of people seeking second careers as therapists, and soon it was struggling to keep up with demand. “The program is a national phenomenon,” says Erdynast. “And it almost didn’t happen.”

A Spirit of Collaboration And Innovation

Cross-campus conferences, events, and collaborations stand out as highlights for Erdynast. In the early ’80s, he organized several faculty conferences that included representation from all of Antioch’s campuses. “It was a great opportunity to discuss and build on all the work being done on different campuses,” he says. “Sharing teaching approaches, research, and bringing various communities together is an invaluable educational experience that elevates the whole university through bringing people together.” The last in-person conference he attended took place in Los Angeles about ten years ago, but with the recent transition away from a campus-based model and towards a university-wide model, that spirit of cross-campus collaboration is stronger than ever.

For Erdynast, the questions of starting a campus and launching new programs tie in with his career-long interest in moral development and education. This, combined with his focus on collaboration, has led to some interesting happenings. In the ’80s and ’90s, he collaborated with Wiktor Osiatynski to develop what he describes as “a BA Program that would focus on landmark Supreme Court cases as a basis of Liberal Education.” One of the central cases they focused on was Roe v. Wade, the 1973 landmark abortion ruling that the current Supreme Court overturned in June 2022. In class, Erdynast explained the importance of this decision to students by citing Thurgood Marshall, the noted Supreme Court Justice who was the first Black man ever to hold that position and who was one of the seven justices to sign the majority decision in Roe v. Wade. “Marshall once wrote that if women lost the right to an abortion, it would condemn many women—especially Black women—to a lifetime of poverty,” explains Erdynast. “Curtailing abortion rights is institutional racism and institutional sexism.”

Another innovative program Erdynast participated in during the 80s was teaching classes in moral development for incarcerated women at the women’s state prison in Chino, fifty miles east of Los Angeles. Erdynast read the latest research at the time, which found evidence that incarcerated people who completed three or more college-level courses had a much lower rate of recidivism. So he brought enrolled (what he calls “free world”) students from the LA campus to the prison, where they attended classes alongside incarcerated students. Several formerly incarcerated women in those courses completed their bachelor’s degrees, and some went on to enroll in graduate studies at Antioch. “Formal education should be offered in all prisons,” Erdynast says. “And in a way that builds relationships with the outside world, so that students who want to can see a clear path to continuing their studies and pursuing careers.”

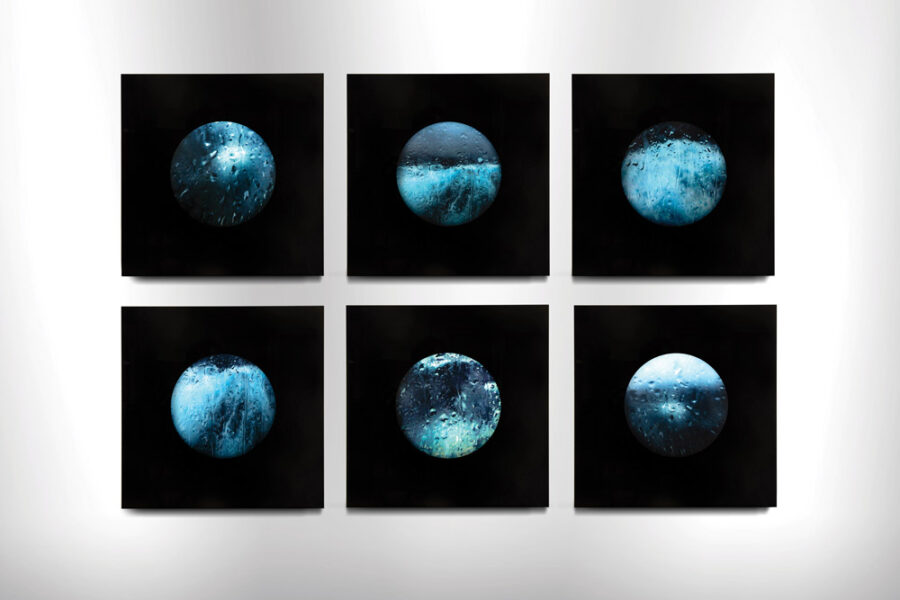

Prison is, to Erdynast’s view, the perfect place to study moral development in particular, as it provides an opportunity to think critically about what brought the student to prison—on both a personal and a societal level—and to consider what they want to do next. Erdynast still remembers a student paper from that time, written for his course on the art of Picasso, that was titled “Beauty is a Bitch.” The student discussed the fraught nature of beauty: how something can be aesthetically pleasant even as it highlights suffering, pain, violence, and trauma, as in the context of Picasso’s paintings depicting the Spanish Civil War. The paper was an exploration of how the artist can also serve as an activist.

For Erdynast, these types of revelations are timeless. “It’s happening in Ukraine right now,” he says. “Art is one way people process traumatic experiences—through creating it, viewing it, and talking about it.”

Ongoing Dedication to Students and LA

Today, Erdynast continues his work at Antioch University. And as anyone who has spent time talking with him knows, he loves to refer to himself as the “senior member of the petrified faculty.” In some ways it’s true—he is among the oldest teachers at the campus. But it’s also ironic because as a teacher and consultant, he strives to stay in motion. He is always improving and evolving his courses, growing with the times, and incorporating what he learns from his students and colleagues.

Ultimately, his greatest legacy is in the classroom. He was happy to hand over directorship of the campus to others who continued building it. In particular, Erdynast credits Dale Johnston, PhD, Distinguished Professor of Humanities and President Emeritus of Antioch University in Los Angeles, who served in the ’90s as both campus president and provost, for cementing the viability of Antioch’s campus in LA. “He brought us to a new level,” Erdynast says, “through improved academic programs, higher tuition, and expanded staff and programming. He retired twice, once as president, but then returned as interim provost and only [fully] retired about five years ago.”

Relinquishing the day-to-day management of the Los Angeles campus freed Erdynast to teach courses ranging from specific studies of writers (Mark Twain) and artists (Picasso) to social and business ethics; from ethics in cinema (Casablanca, Hidden Figures, Imitation Game) to adult psycho-sexual development (Harold Pinter and Antonia Frasier). All of these courses relate to his chosen field of moral development, which has been a lifelong subject of personal and professional study.

Over the years, he has developed his own teaching pedagogy and moral system, which he calls “Four Conceptions of the Beautiful.” He names four domains of human development: factual reality, conceptions of the good, conceptions of right, and generosity and compassion. Erdynast ascribes the development of this system to his thousands of hours spent in the classroom. “I always learn from students,” he says. “Always.”

One area in particular perhaps embodies Erdynast’s work—and the ongoing work at the LA campus—better than any other. That is his ongoing inquiry and teaching around the work of the playwright Harold Pinter and the author Antonia Frasier. This famous literary couple explored in their lives and in their creative works the possibilities of divorce, re-partnering, and a continuous search into upheaval and shifting dynamics in relationships. Erdynast finds the couple endlessly fascinating—and perhaps they could serve as a metaphor for how Antioch has developed over the last fifty years. It has grown, restructured, and changed many times in many ways, but always with the aim of cutting-edge, socially-conscious progress.

“Sometimes, when people marry young, they don’t have a clear sense of who they are yet, who they want to become,” explains Erdynast. “There is a question of whether the spouse will develop alongside of them or in another direction. Divorce is commonly viewed as a failure, but I think it can be viewed as a normal occurrence that honors how people change over time. The United States has a comparatively high rate of divorce, which I see not as a failure, but as exemplifying a unique cultural inclination toward radical self-development and positive change. The same goes for our platonic relationships and alliances.”

Being a constant work in progress is what makes the Los Angeles campus one of Antioch’s success stories. Erdynast saw this possibility back when it was in its early days of bean bag chairs and big dreams. The bean bags are gone, and many of the dreams have since been accomplished. Others have been tried and left behind, while some are still in the process of being realized. The constant is that students, faculty, staff, administrators, alumni—everyone in Antioch’s Los Angeles community—remain committed to keeping eyes open, doing the work. “We are evolving with empathy, integrity, and generosity,” says Erdynast. “It’s an ongoing process, and a worthy one.”