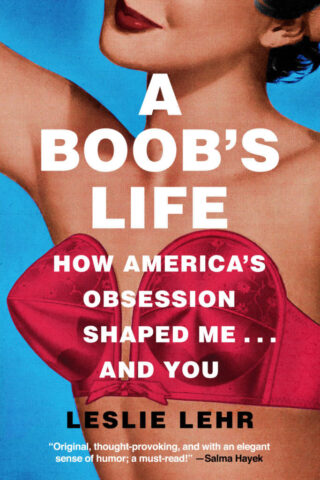

Many writers dream of having their book developed into a TV show. For Leslie Lehr, a 2005 alum of the Antioch MFA in Creative Writing, this dream is coming true. Her 2021 memoir A Boob’s Life: How America’s Obsession Shaped Me… and You was optioned by HBO Max Comedy. Acclaimed actor and producer Salma Hayek said, “Original, thought-provoking, and with an elegant sense of humor, A Boobs Life is a must-read.” And yes, it’s partly about breasts. As Lehr explains, the book tackles “the duality of today’s women, to navigate a new path between sexy and sacred.”

On May 9, a new paperback version of A Boob’s Life came out, with a new chapter and updates that, as she says, “bring the story screeching into present day.” This builds on the original, which was praised by People Magazine, Glamour, and Good Morning America, as well as the literary review services Kirkus and Booklist.

A Boobs Life is Lehr’s fourth book of nonfiction and her seventh full-length publication. Her essays include a New York Times “Modern Love” piece that was read aloud by Katie Couric for Modern Love: The Podcast. She’s also a produced screenwriter. (As a member of the WGA, Lehr supports the current strike.)

We recently talked with Lehr to discuss her life as an author, her memoir, and what having boobs means in this society.

You really seem to write what you know and have clearly found success in it. What advice would you give to young writers, especially female writers, on developing stories they’re looking to publish?

Initially, I wrote to vent. My personal essays weren’t so much “write what you know” but “write what you want to know.” I wanted to know why certain situations were so upsetting. Now we call it having a voice. It’s critical for women to have a voice because the male voice is our cultural default. Publicly, it informs the laws that govern us, and privately, it’s expressed in the books and literature that shape our expectations.

Naturally, I grew up envisioning myself as the hero of every story I read or saw in the movies. Turned out I couldn’t be the hero in real life because of my body—I was both judged and limited by my biology. My first collection of essays, written as a frustrated new mom, became my first book. Even then, the male publisher had me change the subtitle to be more positive.

It’s critical for women to write about our lives because if we don’t, no one will. And while we’ve heard what it’s like to be a man forever, only we know what it’s like to live in a woman’s body. So please, keep writing! Personal essays and memoirs tell Women’s History. Short stories and novels reveal our emotional truth in a way that breaks down the binary thinking of women as either good or bad, Madonna or whore. Put your passion down on paper and make every word count. We need to be heard.

What often motivates you and your work? What women and stories inspire you? What are you reading/watching today?

If money motivated me, I’d be writing fantasy or thrillers, genre stories that could draw a consistent fan base. I wish it did, because I’d love to do nothing but write. But I can only write what I feel passionate about.

I truly want to make a difference, make my life matter. I just spent my recent TV option money to promote the paperback, knowing full well that the small royalty I’ll get from traditional publishing may not return the investment. But every week, I get emails from readers who got a mammogram and early life-saving treatment or vowed to take better care of themselves. I also get letters from women and those who identify as such who now understand how much their self-image is shaped by the culture. Last week, I heard from a woman in the Netherlands who was frustrated all her life until she read A Boob’s Life and realized she’s a feminist. She has five daughters—and now they’ll have a mom who supports their rights. I get letters from men, too. If I can encourage one person to vote for women and families, I consider it a win. Books are not only made from trees, they are like them: if one falls in the forest and no one hears it, did it happen?

I mostly read fiction for fun, and I usually have half a dozen books checked out from the local library. The stories that inspire me are about women who know they can’t do it all but are doing their best and figuring out how to make it work. I also like thrillers because the bad guy gets caught. In fiction, everything has to make sense. Real life is more random. We mainly hear about the success of women who are celebrities because they have help to make it all work. In fact, I paid tuition for my Antioch MFA by ghostwriting a book like that.

Your book has been optioned into a series; congratulations! What are you looking forward to most as your story finds a different audience in streaming?

The financial freedom to write more! My day job is working with other writers, which I love because, after thirty years of publishing, I know how to both develop and fix a story. And I tend to prioritize work when people are paying me. As for the TV show, I’d love to have my voice heard by a wider variety of people, including younger people, more men, and more on the other side of the political divide. A Boob’s Life hit number one in feminist literature while being optioned as a TV comedy. It covers so many topics that everyone can relate to it. I’ll be pleased no matter what.

The never-ending question for creatives: What are you working on now/next?

I just finished a novel that I’ve wanted to write forever. It’s based on a true story, so I tried to write it as a memoir at one point, but it was too painful for a family member, so I put it in a drawer. When the celebrity involved passed away, I realized I could have more fun with it as a novel, playing with all the points of view. It’s a period piece with complicated structure and racial issues. A fellow Antioch alum, the brilliant Cassandra Lane, did a sensitivity read and affirmed that we can’t be afraid to write these stories, we just have to do it right together. I’m excited to get it out there.

Entertainment Tonight called you a “trailblazer.” What does that title mean to you, and how do you plan to hold on to that title with work you may have in the future?

That’s the biggest honor I can imagine. The rest of that sentence describes “women changing the world,” and that is certainly my goal. Writing is the only way I know to do that. A Boob’s Life is a classic that goes beyond one woman’s memoir into a research-backed history of women in modern America for university gender studies departments. No matter what genre I write in, I always focus on the struggles of women. I want to change the world for the better. Stories are powerful that way.

You’re very open when it comes to discussing breasts (obviously!), and our country has such a hard time discussing anything related to sex, often considered “taboo.” But breasts play a huge part in our society from early nutrition to sex, what would you say to those who look the other way and pretend as though breasts aren’t there? Or feel as though a discussion centered around them is “inappropriate”?

Breasts are the first visible signifier of gender—biological instinct causes men to scan them within .002 seconds of a person entering a room. That’s why trans people get top surgery, why breast cancer patients generally opt for reconstruction, and why breast augmentation is the most popular elective surgery for women. But our culture has co-opted this instinct to make money in a way that limits all of us. This is an organ that can both nurture life and kill us, yet fashion thinks it’s funny to say they’re in style or out. There are over 150 nicknames, and women get caught in this double bind of beauty because we live here and need to survive.

Every single day women have to decide what to do with their breasts, to hide them or show them, lift them up, or bolt them down. The physical changes reflect every stage of our lives, and yet we are held to a standard of beauty that defines adolescence. When we are at the bottom of the list of countries with laws supporting women and families, we can’t take boob jokes for granted.

You mentioned in your brief how you had a Trump-voting father. It seems like you may have grown up in a conservative household, or at the very least, know the presence of it now. What was your relationship with breasts as you grew up in a household and a time when this wasn’t “dinner table talk”?

My dad is set up as the main opponent in A Boob’s Life since he was an All-American Ivy League man who collected Playboy, which is representative of our culture. Yet, he had a PhD and encouraged my mom to get hers while also teaching full-time and volunteering for Planned Parenthood. He felt he supported women as equals. I was influenced by his belief that I could achieve anything I wanted—as if I were a boy. But he also voted along party lines, and the Republican Party believes in individualism and states’ rights. He didn’t see that life would be different for me once I had boobs, that women need our rights protected by law. He felt that with every success, I had proved that everything was fine. Plus, he was a scientist who could skew statistics in his favor. We avoided political talk in order to have a relationship. Then last summer, I was invited to ride in the 4th of July parade in my Ohio hometown. Just as I started packing for the trip, Roe v. Wade fell. That’s why I’m so excited about this new paperback. Not only did I get to update all the fact pages, but the new Epilogue is about that visit. I was staying with my dad, and I was so angry. He didn’t understand how his vote betrayed me or my sister or his granddaughters, yet he was so proud of me. Every topic in the book came up over that weekend, and yes, there were fireworks. He died a few months ago, just before we went to press, so I included that. The new Epilogue will give you goosebumps.

Lastly, in reference to Antioch’s social justice mission, how do you see A Boob’s Life falling in line with your own social justice mission? What cultural impact did you see being formed with your book?

A Boob’s Life is both a memoir and a nonfiction narrative with critical analysis. That was the only way I could figure out why we’re so obsessed with breasts. But the structure made it tricky to sell. The hardback came out during COVID, so once the quarantine lifted, I went to New York to sign books at Barnes & Noble. The manager asked whether it should be shelved with Biography or Nonfiction. I couldn’t compete with celebrity biographies nor straight journalism, so I wasn’t sure. But I do think we’ll see more of this creative nonfiction hybrid. Human experience makes the facts relatable. Most chapters of A Boob’s Life are written as personal essay with scene, summary, and analysis. Between each chapter is a fact page that provides historical context, including advertising and censorship, cheerleading, beauty pageants, breast implants, nicknames, Victoria Secret’s supermodels, celebs who posed for Playboy, women who died of breast cancer, and the slow progression of representation in government. The combination of humor and history shows that we can’t change biology, but we need to be aware of how our reactions to it affect our lives. We’re all living A Boob’s Life.